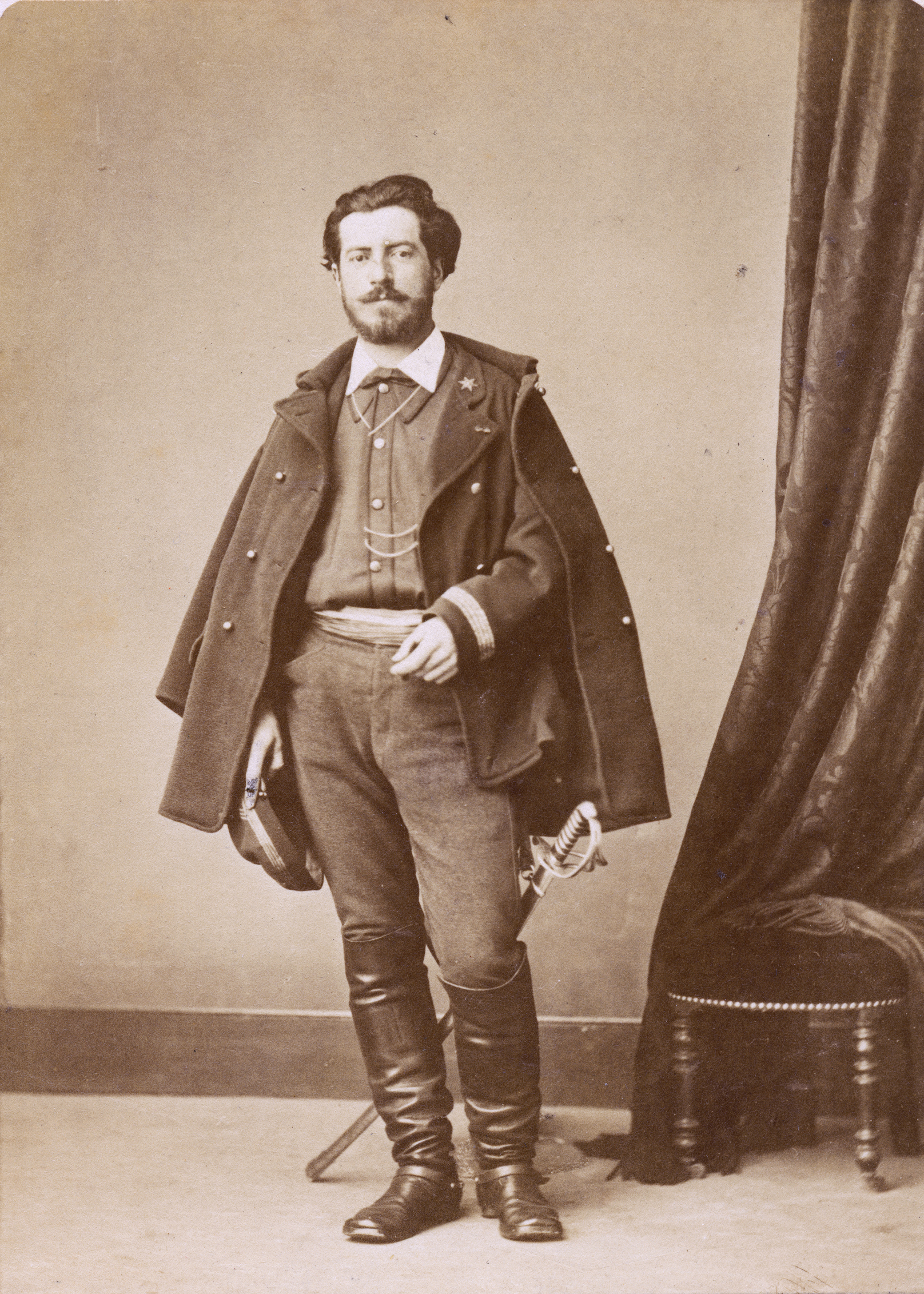

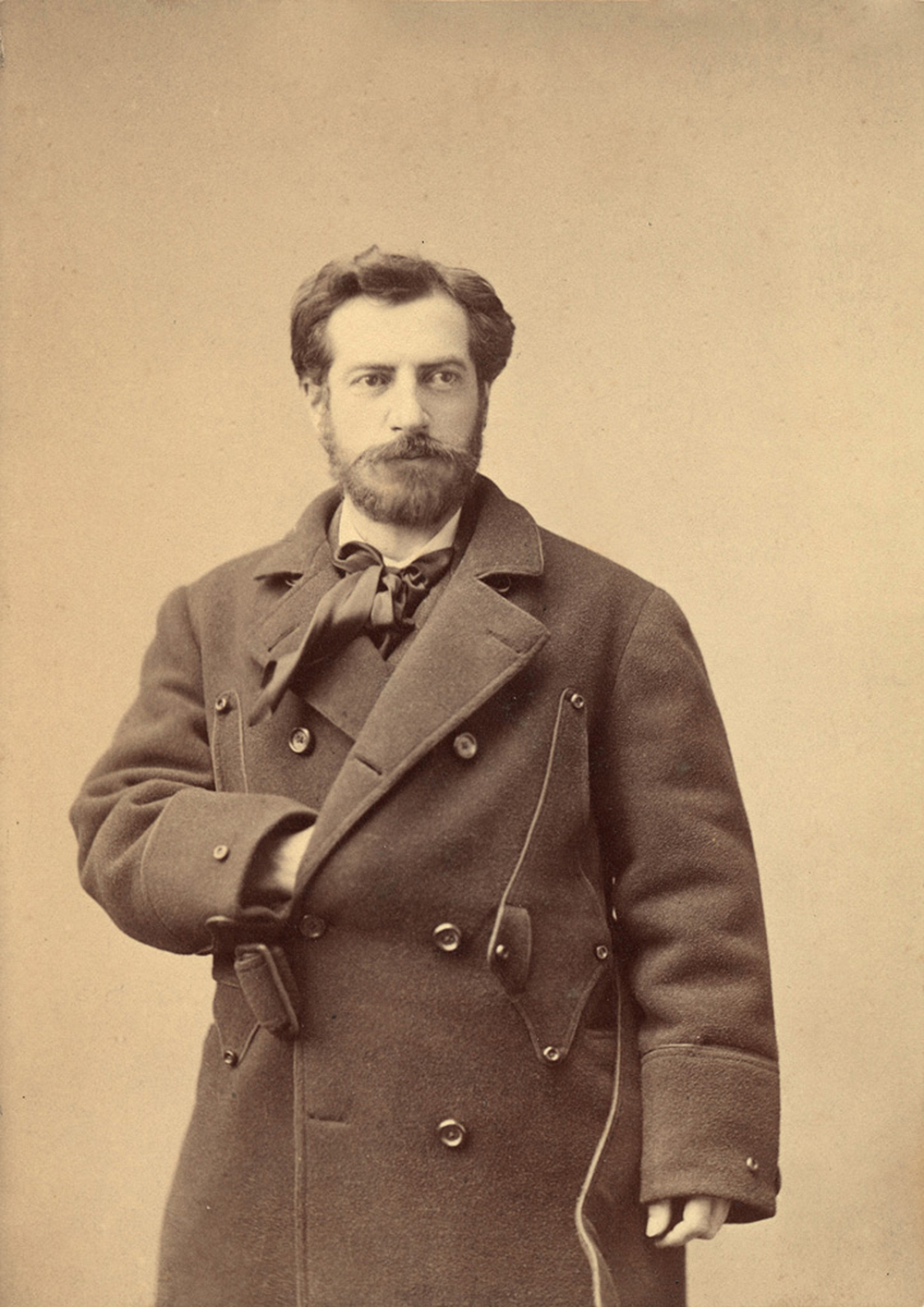

Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi at Chalons-sur-Saone. Photograph by Paul Bourgeois. Musée Bartholdi Colmar. Photograph © Christian Kempf.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Francesca Lidia Viano, author of Sentinel: The Unlikely Origins of the Statue of Liberty, now available from Harvard University Press.

In the above photo, taken in December 1870, the future sculptor of the Statue of Liberty—that symbol of peace and democracy—poses in military uniform. And not just any uniform. The previous summer, Prussian troops had crossed the French border, defeated the regular army, and captured it along with the emperor, Napoleon III. With its army incapacitated, France was expected to surrender. But its citizens were up in arms: with few weapons and horses, they continued to fight in what history records as the first “people’s war” fought on a national scale. Frederic-Auguste Bartholdi was among them.

Bartholdi’s assignment was to provision the army of volunteers under the command of the legendary independence champion Giuseppe Garibaldi, who had traveled to France to help the irregulars. One day, scavenging for food and weapons in Bordeaux, Bartholdi found the transatlantic Lafayette waiting to unload guns and clothing that Americans had sent to France in violation of U.S. neutrality. Bartholdi boarded the ship and questioned the sailors about America’s attitude toward the Germans. Reassured about Americans’ loyalty to France, Bartholdi returned to camp, bringing ammunition and guns—and also a new idea for a project that he had left unfinished before the war: a statue lifting a torch and crowned by rays.

After France lost the people’s war, Bartholdi knew what to do about the statue. He boarded a ship to New York to propose her to the American people as an icon of Franco-American friendship. This was the official meaning of the giant copper beacon. For him, however, the statue was a promise of French vengeance against the Germans. Significantly, along with drawings for the statue, Bartholdi also carried with him to America his Garibaldinian uniform and posed with it in front of a New York photographer. Perhaps he thought that proof of his Garibaldinian past would help him sell his statue of liberty in America. Without Garibaldi and the French people’s war against Prussia, after all, what we think of as the Statue of Liberty would have looked very different, had she existed at all.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Rosellen Brown, author of The Lake on Fire

• Leland de la Durantaye, author of Hannah Versus the Tree

• Patricia Miller, author of Bringing Down the Colonel

• Helen Klein Ross, author of The Latecomers

• Monica Muñoz Martinez, author of The Injustice Never Leaves You

• Tatjana Soli, author of The Removes

• John Wray, author of Godsend

• Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine

• Ken Krimstein, author of The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

• Katherine Benton-Cohen, historical adviser for the film Bisbee ’17

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing