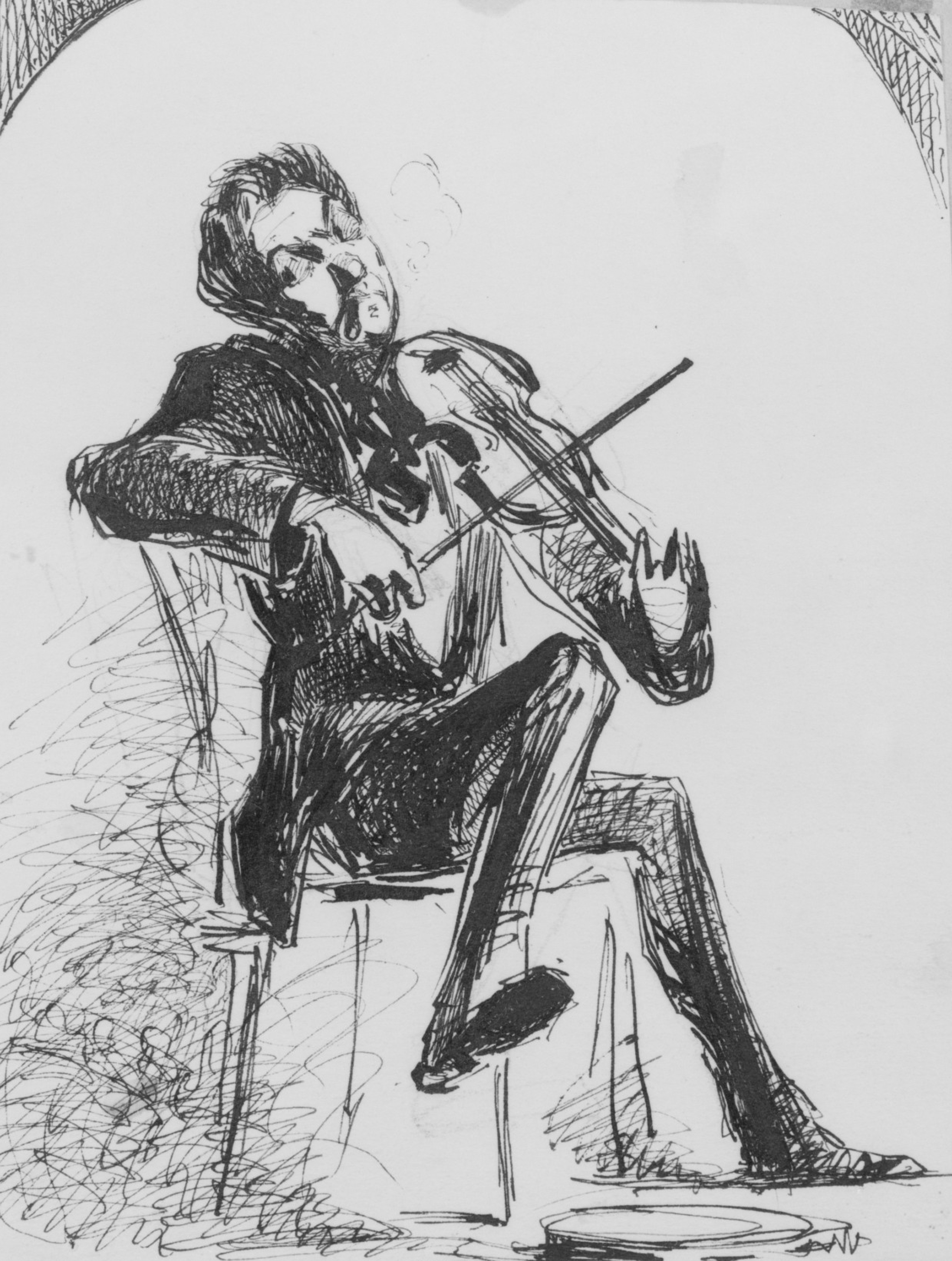

Ross Winans Playing Violin, by James McNeill Whistler, c. 1855. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Margaret C. Buell, Helen L. King, and Sybil A. Walk, 1970.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

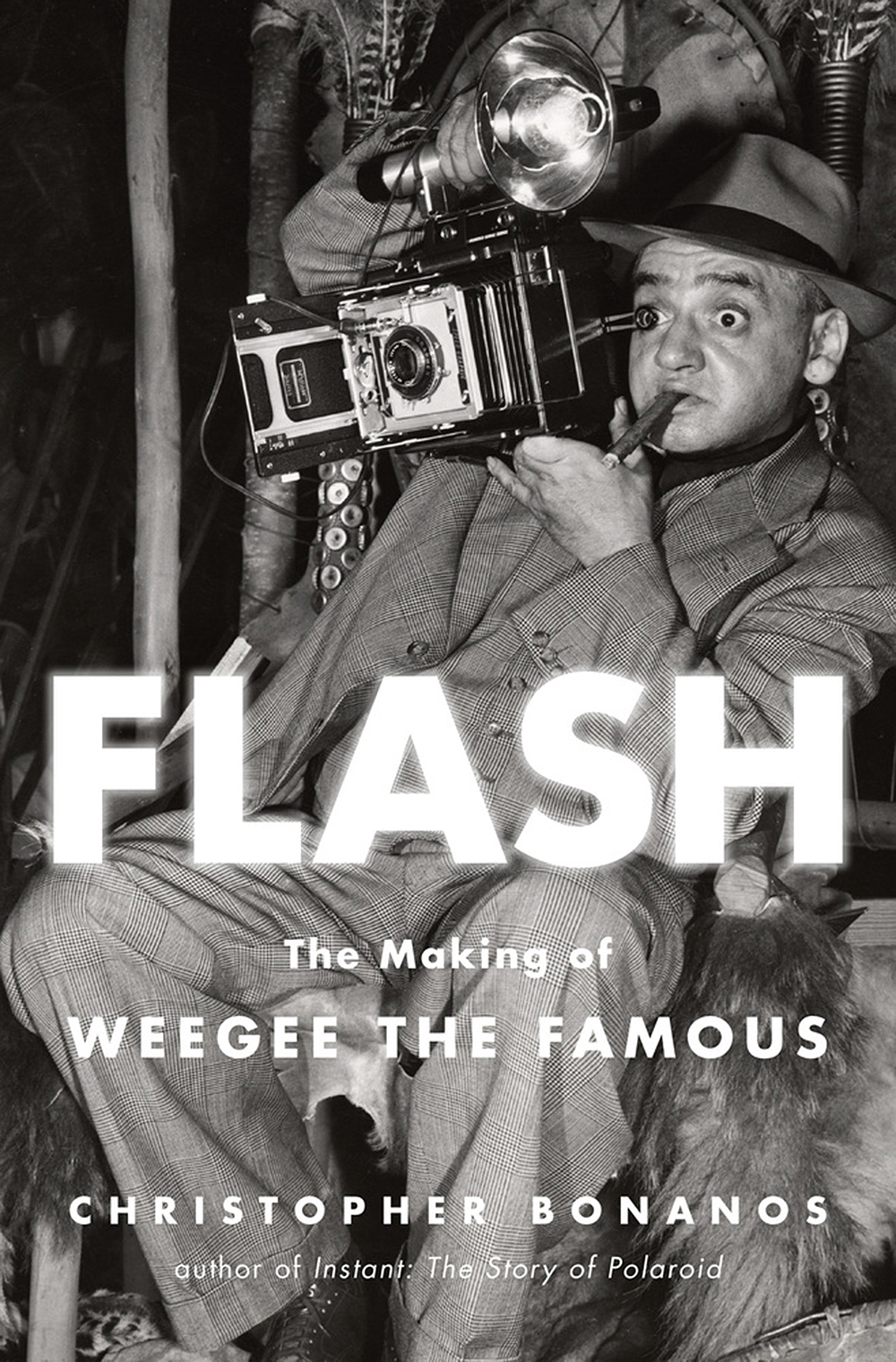

This week’s selection comes from Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous, out now from Henry Holt and Co.

Before he became Weegee the Famous, the pseudonymous photographer who raced to crime scenes and fires and other mayhem in the New York City night, Arthur Fellig was a Lower East Side street kid. He had come to America from Eastern Europe at ten, and he worked every hustle he could think of to make a living, get out of his parents’ packed tenement apartment, meet girls, maybe get somewhere in life. He took jobs in the Life Savers factory—he said he was “a hole puncher”—and at the Sunshine Biscuits bakery. He sold candy in the streets to garment-worker girls. He bussed dishes in the Automat.

And, for a few years, he played a cheap violin, not especially well, as an accompanist at a silent-movie theater. It was a formative experience, he said, because he learned how to work the emotions of an audience. A decade later, as he embarked on his career making photographs for the tabloids, that knack translated itself from music to pictures. Weegee’s images of underclass life often function as little one-act plays, the visual equivalent of that story spuriously attributed to Hemingway (“For sale: Baby shoes, never worn”). Weegee was often referred to as “O. Henry with a camera.”

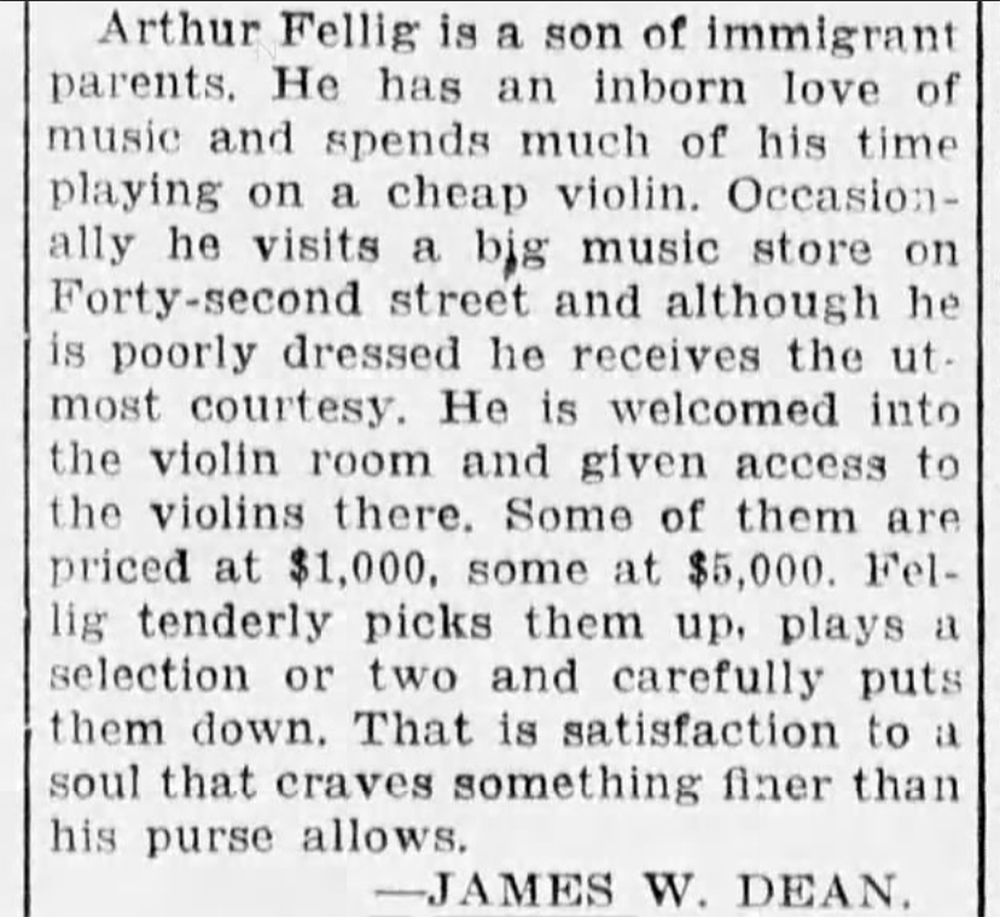

In 1924 Arthur Fellig was just beginning to figure out his future. He’d quit the movie theater and taken a job in the darkrooms of Acme Newspictures, a photo service that eventually became part of United Press International. There he occasionally cadged the odd news photography assignment. At Acme, he also met a columnist named James W. Dean, who wrote a regular column for out-of-town papers called “In New York.” It was a chatty dispatch that was usually filled with anecdotes from the big city—including one about his colleague’s visits to a violin shop in Times Square. This particular version of Dean’s column, which was syndicated all over the country, appeared in the Palm Beach Post on November 19, 1924.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Sander L. Gilman, author of Stand Up Straight! A History of Posture

• Alastair Bonnett, author of Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

• Scott Samuelson, author of Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Stuart Kells, author of The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Sarah Henstra, author of The Red Word

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing