“Saving Daylight!” 1918. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

On August 15, 2015, Kim Jong-un had everyone in North Korea set back their clocks by thirty minutes. He turned back the hands of time in both a literal and figurative sense. The newly created Pyongyang time zone, a celebration of seventy years of Korean independence from Japan, evoked a more idyllic era of a united Korea before its occupation. When Japan colonized Korea in 1910, all the clocks were moved forward thirty minutes to Japanese time, where they had henceforth remained. And just as the initial switch in time zone signaled a consolidation of power for Tokyo, so too was Kim’s switch back a symbolic gesture of contempt—at least according to the country’s state news agency—for the “wicked Japanese imperialists.”

The case of Pyongyang time is far from the only example of an authoritarian changing a territory’s time zone as a means of asserting political control. And although setting clocks back or forward is often seen as one of the more benign uses of power (akin to changing a nation’s flag or national anthem), it’s interesting to note that ever since time zones began standardizing in the mid-nineteenth century, the manipulation of time has proved to be an almost irresistible draw for authoritarian rulers.

Prior to the industrial revolution, local time everywhere was informally based on the movement of the sun—most people lived in the countryside on a schedule that revolved around tending to their animals and crops. With the invention of the mechanical clock, cities began using a more uniform (and locally specific) mean solar time. It wasn’t until the spread of intranational railways that hourly time zones came into being, largely to avoid confusion with train schedules. In 1880 an act of parliament declared the whole of Great Britain officially under Greenwich Mean Time (GMT). Soon thereafter, many other countries followed suit, eventually aligning their own time zones in relation to that of the administrative center of the world-spanning British Empire.

While smaller countries, like the United Kingdom, made the switch to a single hourly time zone fairly easily, the standardization of time posed a slew of problems for larger nations. Russia was in a particularly difficult situation. In 1880, while the populace was still using local solar time (based on “solar noon,” when the sun is at its highest point in the sky), Tsar Alexander II decided to run the trains on St. Petersburg time across the country—a move likely as much a matter of administrative convenience as a show of power. Those operating the moving trains had no problem keeping track of St. Petersburg time, but because the time on the train schedule was often different from the local time where it was making stops, “it was terribly confusing for passengers,” says Anton Fedyashin, director of the Carmel Institute of Russian Culture and History at American University. “Solar time lasted until 1919, when the Bolsheviks, somewhat ironically, Westernized the measuring of time.” Fedyashin notes that although the Bolsheviks were authoritarian, they were also “modernizers, bringing Russia into the modern age.” (After all, if they hoped to spread an international political movement, they needed to join the international community first.)

From the very beginning, standardized global time zones were used as a means of demonstrating power. (They all revolve around the British empire’s GMT, after all.) A particularly striking example of this happened in Ireland. In 1880, when the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland declared GMT the official time zone for all of Great Britain, Ireland was given its own time zone. Dublin Mean Time was twenty-five minutes behind GMT, in accordance with the island’s solar time. But in the aftermath of the 1916 Easter Rising, London’s House of Commons abolished the uniquely Irish time zone, folding Ireland into GMT, where it remains to this day.

Early changes in time zones were certainly power moves to some extent. By the 1930s, though, once most nations had established permanent time zones for themselves, alterations in a nation’s sense of time were often a result of authoritarian conquest. The World War II era was rife with these changes, particularly as the Axis powers conquered their neighbors. When Japan invaded Malaysia in 1942, Malaysian clocks were reset to Tokyo time—a move reversed at the end of the war. Meanwhile in Europe—as if the constant adjustments and readjustments of daylight saving time in order to save fuel weren’t enough—as Hitler’s armies advanced across the continent, time zones were changed to align with Berlin. In 1940 occupied Holland moved the country’s clocks an hour ahead to Central European Time. Shortly thereafter, the new government of Vichy France followed suit; Spain’s Francisco Franco did the same. But unlike Malaysia, these three European nations never went back to their prewar time zones.

“For Franco, it was a clear political move to indicate Spain’s alliance with Germany,” says David Messenger, historian of modern Spain and chair of the history department at the University of South Alabama. “And after Germany was defeated, why go back and admit the mistake?” Many argue that Spain’s “incorrect” time zone explains why Spaniards eat dinner so late, but Messenger is skeptical. “If they went back to GMT, wouldn’t dinner be at nine instead of ten?” His theory is that it’s the siesta that throws off the dinner schedule, since people leave work later because they have a two-hour break in the middle of the day. And even after work, they’re likely to stop at a bar or coffee shop for a drink before heading home. “I have also heard an economic argument,” he adds. “In earlier days, many poor Spaniards worked two jobs and the siesta was the break between the two jobs, and working the second job would also explain late dinner.”

Messenger notes that at least once a year in the past few years, someone in the Spanish parliament brings up the possibility of moving Spain back to GMT. “Numerous studies recently have shown Spanish workers are less productive than others in Europe,” he says, “which is one reason there’s a push for the time change now.” However, now that the whole European Union is ditching daylight saving time, letting each member country decide whether it would like to remain on winter or summer time year-round, the situation could get even more complicated—especially with Brexit. (In what could turn out to be a future instance of power asserting itself through controlling time, Brexit could very well result in the absurd case of Ireland existing in a time zone different from Northern Ireland’s.)

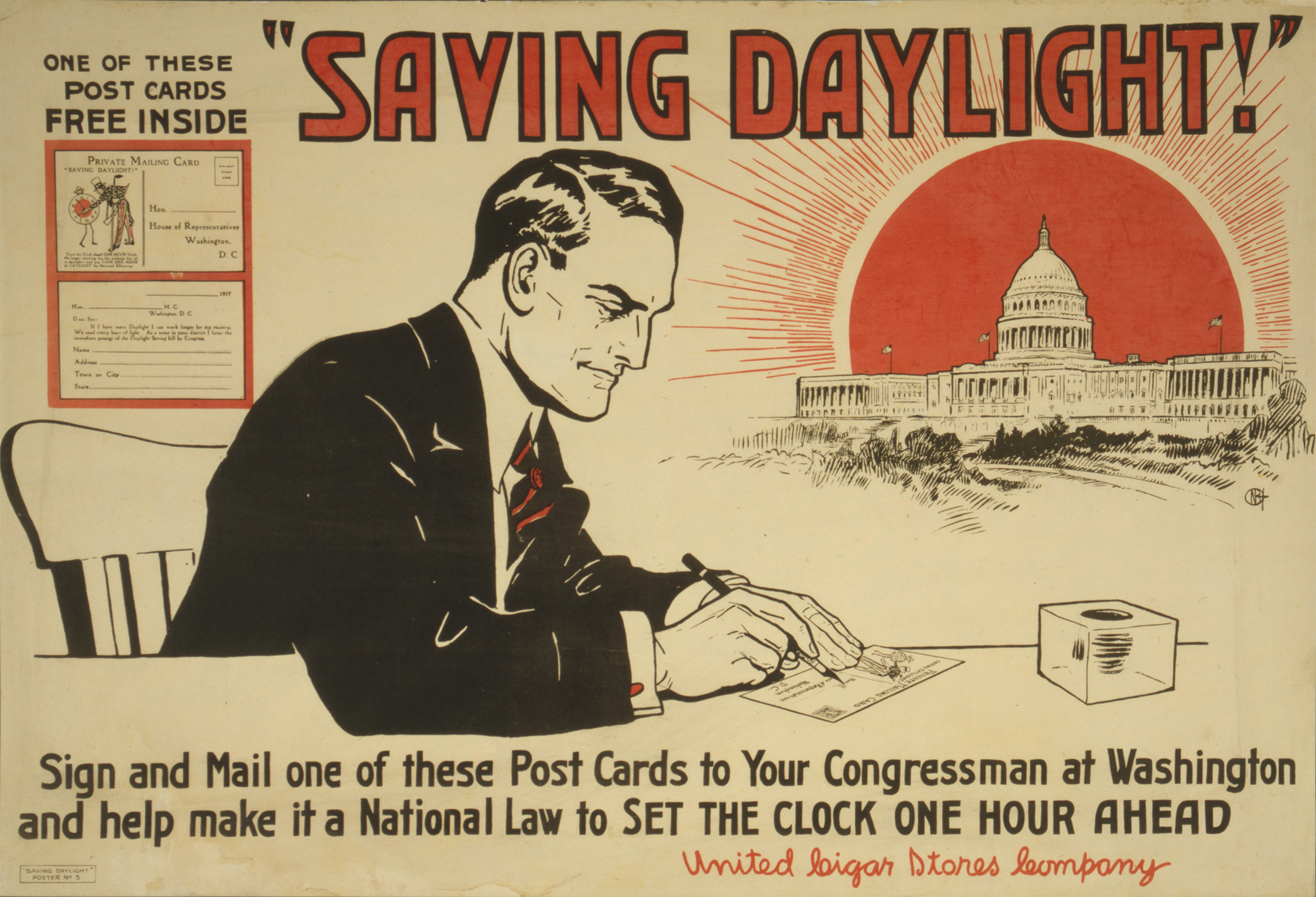

Let’s take a step back for a moment to discuss daylight saving. Although the idea for it first came up on the heels of worldwide hourly time zones, daylight saving time wasn’t implemented on a national basis until 1916, when Germany and Austria-Hungary adopted the twice-yearly time change in hopes of saving energy during World War I. (Much of the rest of Europe, as well as the U.S., soon followed suit for the same reason.)

“The German reason for adopting it in 1916 was to get another hour of daylight during production periods and thus save fuel running factories that were making weapons,” Messenger explains. “So not necessarily to be more productive in terms of producing more weapons, but to be more efficient and save some money. And it did work in that sense.”

When the war ended, so did Germany and Austria’s daylight saving time—only to be brought back at the onset of World War II. Like Germany and Austria, countries around the world have adopted daylight saving time, nixed it, readopted it, re-nixed it. (Russia, for example, has gone back and forth several times, most recently settling on year-round standard time in 2014.) Since the beginning, farmers the world over have been pushing to get rid of daylight saving, as changes in feeding times often confuse and stress their livestock. Today, there’s a skepticism as to whether moving the clocks forward an hour every spring really saves much energy, especially in the modern era, when it’s not just lighting and heating that use energy, but also electronics and air-conditioning; some have even argued that later sunsets lead to people driving around more after work and school in warmer months, thus using more energy than they would otherwise.

If you’ve ever been to China, you may wonder how and why such a sprawling country should exist in a single time zone. The answer is Mao.

In 1949, at the end of the Chinese Civil War, Mao Zedong announced that the whole country would set its clocks permanently to Beijing time. The reasoning was national unity; the move fit neatly with the Chinese Communist Party’s consolidation of power. And even though China has changed in many ways since Mao’s death more than forty years ago, the single time zone remains. “It’s not so much the legacy of Mao as the primacy of Beijing,” says Annika Culver, associate professor of East Asian history at Florida State University. “To those far from the PRC’s national capital, it seemingly highlights the subservience of far-flung provinces, many populated by non-Han majorities, of whom certain populations don’t even speak Chinese.”

In the northwestern territory of Xinjiang, the autonomous region where Uighurs make up almost half the population, the issue of time has become politicized. Josh Summers, who has lived in Xinjiang on and off since 2006, documenting the region in his FarWestChina blog, says that the solar-time difference between Beijing and the westernmost city of Kashgar is similar to the difference between New York and Los Angeles. “People live life according to the sun,” he says, “so they work from ten to seven instead of eight to five, and school starts at nine or ten am.” And even though official time goes by Beijing’s clocks, there’s also a local “Uighur time” two hours behind.

“It’s a form of rebellion against Beijing,” Summers says, which makes it confusing for foreigners to know when to meet people. “If I’m talking to a Chinese person, I check with them, and they usually mean Beijing time, but my Uighur friends go by Xinjiang time,” he says. “If you turn on the TV to a Uighur state-sponsored station, it also follows Xinjiang time.” Summers adds that the government knows people are operating on two different time zones, and so far, there haven’t been any major crackdowns. (Of course, the Uighur population, erroneously regarded as a separatist Islamist group, has seen many other types of crackdowns recently—from constant ID checks and surveillance to mass arrests and detention in political “reeducation camps”—but the issue of Uighur time seems to be low on Beijing’s list of priorities.)

The mid-twentieth century saw the most politically motivated changes in time zones around the globe. These days, the world is so interconnected that it’s increasingly difficult to justify a time-zone change. (Unless new territory is acquired, that is. When Russia annexed Crimea in 2014, for example, the peninsula’s clocks advanced to Moscow time, an event marked by an official ceremony at the Simferopol train station.) When changes do occur, they’re typically reversed.

In 2007, Hugo Chávez declared a unique time zone for Venezuela, setting the nation’s clocks back by thirty minutes. (He’d already tweaked the national flag in 2006.) John Polga-Hecimovich, assistant professor of political science at the U.S. Naval Academy, points out that although the official reason for the change was that Chávez didn’t want children going to school in the dark, the new time zone was announced shortly after the Venezuelan public rebuffed Chávez’s national referendum. “Chávez changed the time zone to show his power,” Polga-Hecimovich says. “A shift of thirty minutes is very political, a way of thumbing his nose at the world.”

It may have been rash, but not completely random. Like Kim in North Korea, Chávez had a historical and nationalistic reason for the change, as Venezuela’s time zone had been offset by thirty minutes between 1912 and 1965, before adjusting (albeit quite late) to the international standard.

“The half-hour change in Venezuela meant that most people started using electricity a half hour earlier in the evening, further stressing the country’s outdated electrical grid,” Polga-Hecimovich says. “Many Venezuelans also enjoyed a half hour less of light in the evenings, which could have affected their health (although I have no proof to back up this claim).” Polga-Hecimovich notes that when Chávez changed the time zone, people tended to either support or reject the move based on whether or not they approved of Chávez as a leader; but considering the many crises that Venezuela saw in the 2000s, a change in time zone was the least of its residents’ worries. Venezuela’s fractional time zone wouldn’t last long either. In 2016, three years after Chávez’s death, Venezuela’s new president Nicolás Maduro did away with it.

On a personal note, Polga-Hecimovich, whose wife is Venezuelan, remembers that figuring out the time zone was “always a mess” when they visited Venezuela or tried calling friends and relatives there on the phone, especially when taking daylight saving into consideration. “The initial time-zone change was confusing—as was reverting back to −4:00 GMT under Maduro—but once the country adjusted, I don’t get a sense that it was something that consciously affected people’s daily lives,” he adds. “It seemed to me that people came home earlier and ate dinner earlier in the evening, since it was dark by six pm year-round, but I’m not sure they were even aware of this. My cousin’s daughter, who had to wake up at four thirty am to go to school during the late 2000s and early 2010s, still woke up in the dark during that time—she just enjoyed a half hour less of light in the evenings after school.”

Back in North Korea, Pyongyang time was even more short-lived. In May 2018, less than three years after he announced it, Kim abolished the new time zone, realigning North Korea with South Korea and Japan. “Since after the Korean War, Japan has been a kind of frenemy to both Koreas in terms of aid and personal relationships between peoples,” Culver says. “For Kim, once the symbolism has run its course, it might be more strategic to rejoin the international norm, as he strives to prime his global image as a sovereign de facto nuclear state with some measure of control over the unification process,” and especially now that the Koreas are talking about linking roads and railroads. After all, time-zone changes of this kind are often merely symbolic. Frivolous time-zone changes are likely a thing of the past if even North Korea understands this. Of course, we’ll have to see what happens first with daylight saving time—both in the European Union in 2019 and closer to home in California, where in a November ballot proposal, nearly 60 percent of voters cast their ballots against “falling back” and “springing forward” every year.