From The Celebrated Trial, Madeline Pollard vs. Breckinridge; The Most Noted Breach of Promise Suit in the History of the Court Records, 1894. The New York Public Library, History of Women Collection.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Patricia Miller, author of Bringing Down the Colonel: A Sex Scandal of the Gilded Age, and the “Powerless” Woman Who Took on Washington, now available from Sarah Crichton Books.

For my book Bringing Down the Colonel, I spent countless hours in archives over a period of ten years painstakingly re-creating the lost world of a late Gilded Age sex scandal that rocked Washington, DC. I pored over letters and diaries, painstakingly deciphering faded and flowery nineteenth-century handwriting. I made myself dizzy reading period newspapers on whirring microfilm machines. But through all my research, I never really saw the face of the woman who was the protagonist of my story until one day last spring.

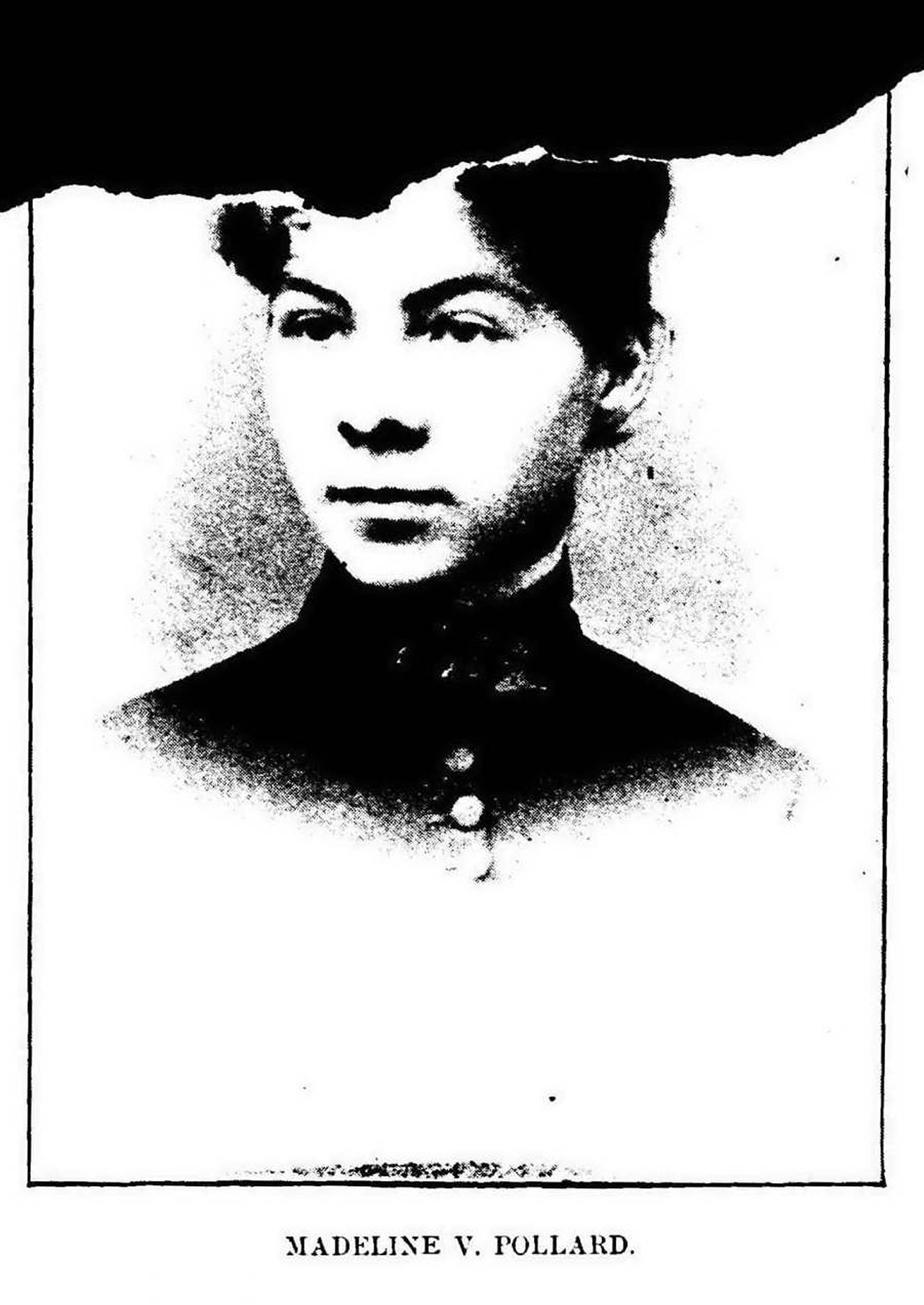

Madeline Pollard shocked the nation in 1893 when she sued esteemed Kentucky congressman William Campbell Preston Breckinridge for $50,000 for breach of promise to marry. The suit revealed that she and the then-married Breckinridge had carried on an affair for nearly ten years—but also outed Pollard as a “fallen” woman in the process. It was inconceivable to most Victorians that she should do such a thing—especially since Breckinridge, whose wife had died, had since married a more socially prominent woman, so Pollard couldn’t use the suit to pressure him into marriage. He also wasn’t a wealthy man, so there was little chance she would see any money. But Madeline didn’t think he should get off scot-free while she was expected to slink away in shame. “I’ll take my share of the blame. I only ask that he take his,” she said.

Even as I dissected the five-week trial and delved into Madeline’s background as a poor, fatherless Kentucky girl desperate to rise in the world, she remained, at least physically, somewhat unknowable. I had a grainy reprint of a photo of her as a seventeen-year-old student—which, she said, was when she met Breckinridge and he seduced her one night during a carriage ride—and the courtroom sketches and crude reproductions of her photograph in the newspaper, but these didn’t depict a flesh-and-blood woman.

Then, one day after I had completed the manuscript, I was searching the database of the Bell Studio archives held by the Library of Congress. The C.M. Bell Studio was the most fashionable portrait studio in Washington in the 1880s and 1890s; I was looking for photographs of some of the secondary characters in my book, many of whom were exactly the types of elite Washingtonians who patronized the studio.

It was late in the afternoon and I was already thinking about dinner, when, on a whim I entered Madeline Pollard’s name. Four photos—digital images of the original photographic plates—popped up. When I clicked on the first one, I literally jumped back in my seat. I knew immediately it was Madeline Pollard—in the flesh. Suddenly this woman I had spent so much time with became more than words on a page. I could see the expression on her face, the exact clothing she had worn during the trial, the hairstyle and hatpin that had been described in countless newspaper accounts.

A little digging in the logbooks of the studio revealed that a newspaper—the New York Herald—had paid for the portrait session right in the middle of the trial. If it hadn’t, I would have never gotten to see the real Madeline Pollard. For me, this chance encounter with Madeline’s photograph is symbolic of how women are often erased from history. Madeline’s whole story, her fight to end the double standard that considered women who had sex outside of marriage irredeemably ruined—and to hold Breckinridge to account for the harm he had done to her—had been lost to history, even though at the time it was a major rallying point for women who were just starting to move into the public sphere and were primed take a stand against men like Breckinridge who abused their power and status and “ruined” countless young women. But her picture brought Madeline Pollard back into the light—and with it her story.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Helen Klein Ross, author of The Latecomers

• Monica Muñoz Martinez, author of The Injustice Never Leaves You

• Tatjana Soli, author of The Removes

• John Wray, author of Godsend

• Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine

• Ken Krimstein, author of The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

• Katherine Benton-Cohen, historical adviser for the film Bisbee ’17

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing