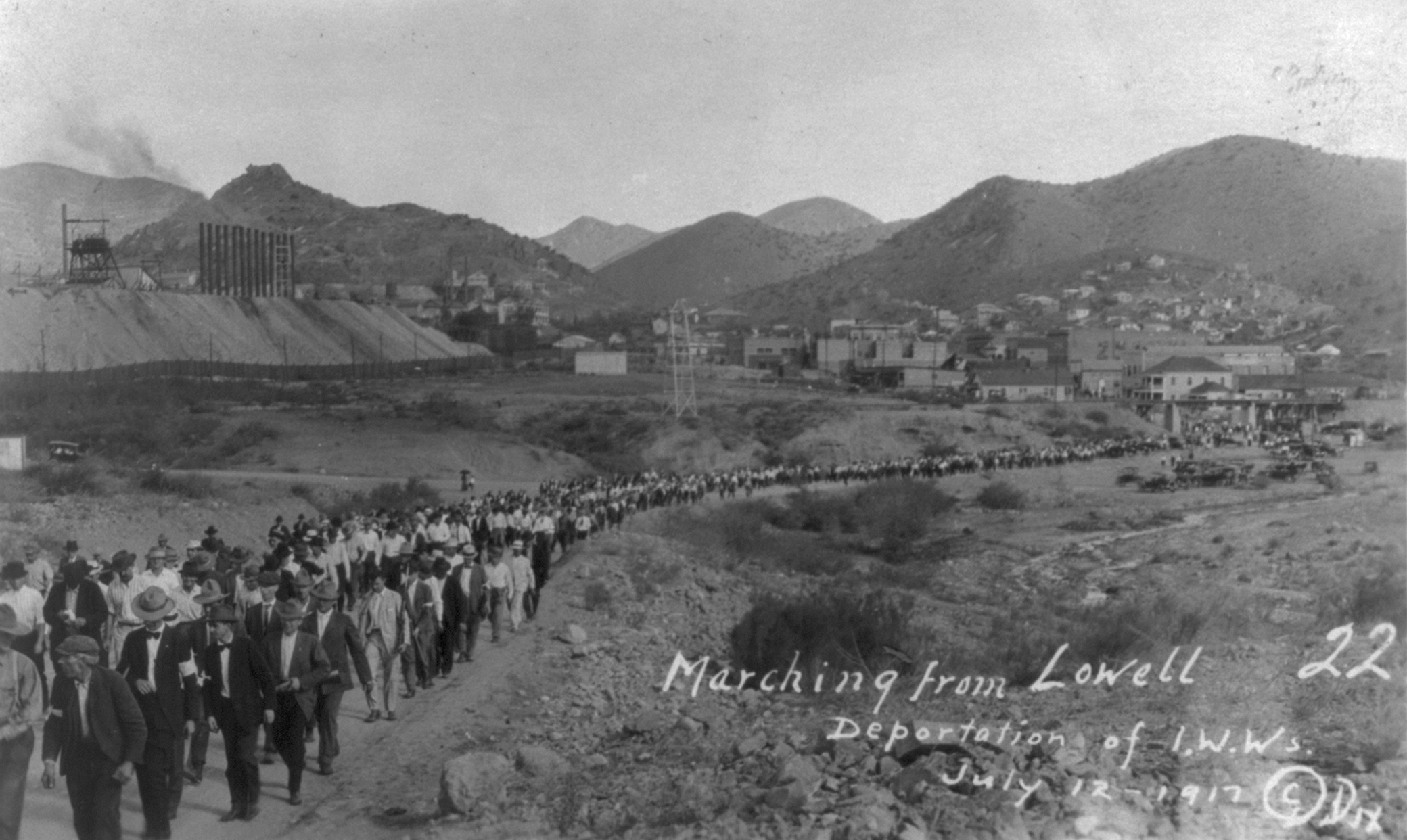

Marching from Lowell, by George C. Dix, 1917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Katherine Benton-Cohen, an associate professor of history at Georgetown University who served as historical adviser for the nonfiction feature film Bisbee ’17.

On July 12, 1917, the town of Bisbee, a copper-mining camp near the Arizona-Mexico border, erupted in conflict. Three weeks into a strike by the radical union the Industrial Workers of the World, better known as the “Wobblies,” nearly two thousand armed men rounded up 1,200 strikers and their sympathizers, marched them two miles through town, and loaded them onto twenty-three company-owned boxcars. Under the hot summer sun, the company shipped the men into the middle of the New Mexico desert, where they were taken in at a nearby army camp. Some stayed there as long as two months. Ninety percent of the kidnapped workers were immigrants, hailing from nearly three dozen countries, and most never returned to Bisbee. The event that came to be known as the Bisbee Deportation prompted a federal investigation whose members included a young Felix Frankfurter, but the perpetrators—among them the county sheriff and many copper-mining executives—were never punished.

In the century that followed, few townspeople dared to discuss the event that had torn their town in two. But as the centennial approached in 2017, a committee of Bisbee citizens planned a series of events to commemorate the still controversial incident and its aftermath. Bisbee ’17 looks at the dark past they confront. Below is a conversation between the film’s director, Robert Greene, and its historical adviser, Katherine Benton-Cohen.

Bisbee ’17 will open for theatrical release on September 5 in New York before opening nationwide.

Robert Greene: One of the things that is extraordinary about the Deportation is that there are dozens of photographs of it. Most that you see are of the long lines of people being marched through town. When these images are seen, most people think: first, how could this happen in America, and second, what other things remind one of an event like this?

But those images and the reactions they provoke take you out of the story—and almost force you to compare the Deportation to other places or moments in history—prison camps, or even the Holocaust, for example.

But the Deportation happened in a particular context, in a particular tiny town. The image here is the one I could not stop looking at and thinking about. The perspective is unusual: it’s looking up the hill toward the cattle car, and there is action in the scene. You can’t tell who’s being thrown onto the car, but you see a mob on top and around it. There’s a guy with a gun and it’s a very active image—he’s actively moving with a gun, and what looks to be a deportee is staring at the camera.

Katherine Benton-Cohen: I learned so much from your discussion of that image, because I don’t see it through a moviemaker’s lens.

Greene: In movies, anytime someone is looking at the camera, it’s basically an indictment of us as viewers. The image itself looks like it’s a scene taken from a Western. When you think about what might be going on in the photographer’s mind, the image he’s creating might be seen as an expression of the idea of the “Wild West.” With this framing, in this dangerous moment, the photographer is essentially re-creating the myth of Wild West. The image captures vigilantes learning to be vigilantes in real time. It’s a human drama, full of mythologies and enactment, and for me, that aspect moves it from abstract history to an urgent image of the present.

Benton-Cohen: Yes, Harry Wheeler, the head of the Deportation, very much thought of himself in terms of the iconic western cowboy. He’d been the captain of the Arizona Rangers before becoming the sheriff of Cochise County. The region was full of cowboys—it had even, as you show in the movie, been the home to the shootout at the OK Corral.

Greene: When we were shooting the scene, reenacting people being thrown onto the cattle cars, we didn’t plan every shot. It was filmed as most documentaries are filmed: we would set up the story (based partly on sources and sketches you and I created), but then the subjects on camera would do what they felt in the moment, and we would find the images within that. It was incredibly collaborative in that way.

Even so, this particular image was always on my mind, and I wanted to try to match it as close as we could to the original. And so, at that moment, we were doing essentially the same job the photographer was doing one hundred years prior, and we found this hauntingly analogous image.

In the film version of the image, we don’t have anyone looking at the camera. But at that point in the film this recognition of the camera was unnecessary. For me, it was one of the most haunting moments of the whole shoot—past and present completely collapsed for me. If you think about a photographer at the time, thinking about the Wild West, as he’s experiencing this very real event, then think about us today making a movie that uses the Western genre as a jumping-off point. While using the present to conjure this event from a century earlier, it’s all about image and history and consequences getting mangled in your brain. I knew the framing by memory, but the results were still captured spontaneously.

Benton-Cohen: One of my favorite scenes in the film is when local artist Laurie McKenna, who plays the photographer, pops her head out from the cloth behind her camera. She’s witnessing what’s happening, but she’s also exposing herself as an actor in the event and a participant in the production of the images of the event that becomes the film. Almost all of the extant images of the Bisbee Deportation come from one professional photographer, though nothing is known of him, except that it seems likely that he was hired by the mining companies. And that in itself is telling—far from this event being shameful or secret, it was out in the open and preserved for posterity. To me, it’s kind of like the communal “witnessing” intended by photographs of lynchings in the Deep South in the same period.

Greene: For us, even building the prop cattle car was emotional. It was unnerving and galvanizing and it felt a bit like we were participating in some sort of conjuring—the ghosts felt present. They felt revealed.

Benton-Cohen: As a historian whose job it is to collect and to compare conflicting primary sources—in fact, that was the job I was assigned by you for the film—it is tempting but dangerous to see photographs as “accurate.” For historians, it’s all about what’s not in the shot. While you’re thinking about the past and present colliding when you look at that image, I’m thinking about what’s outside the frame and how incredibly sexy and seemingly “true” a photograph can seem when it can actually be very deceiving. If I had only seen that one image of the Deportation (which only shows men), for example, and hadn’t looked at the dozens of other ones, or read hundreds of written sources and oral histories, I would not have known that the events of July 12 were full of women protagonists, on all sides. Women fought the deportation of their husbands and brothers, they came out by the hundreds to witness and protest the violence, and some also formed a “relief” committee that handed out railroad tickets and food rations to the women whose husbands were deported. One woman, Rosa McKay (the subject of Bisbee ’17 Short Film #3), even served as one of Bisbee’s state legislators and brought a group of women by automobile to the deportee camp in Columbus, New Mexico, to bring food and supplies and to check on the men’s living conditions. Her testimony to the Presidential Mediation Commission was one of the sources I found most compelling. In the end, though, what I found about the film is that unlike traditional, “talking head” documentaries, Bisbee ’17 ends up as raw and messy as “real” historical practice is. Primary sources reveal a multitude of perspectives that we can never fully reconcile, especially for an event like this one. That is why—unexpectedly—one of the most important qualities a good historian needs is empathy. I see empathy in the film and its protagonists as they wrestle with the past, as well as the way Robert approached them.

This interview has been condensed and edited.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Emily Ogden, author of Credulity: A Cultural History of U.S. Mesmerism

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing