City of Flint Parks & Recreation Department.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy, out now from Metropolitan Books.

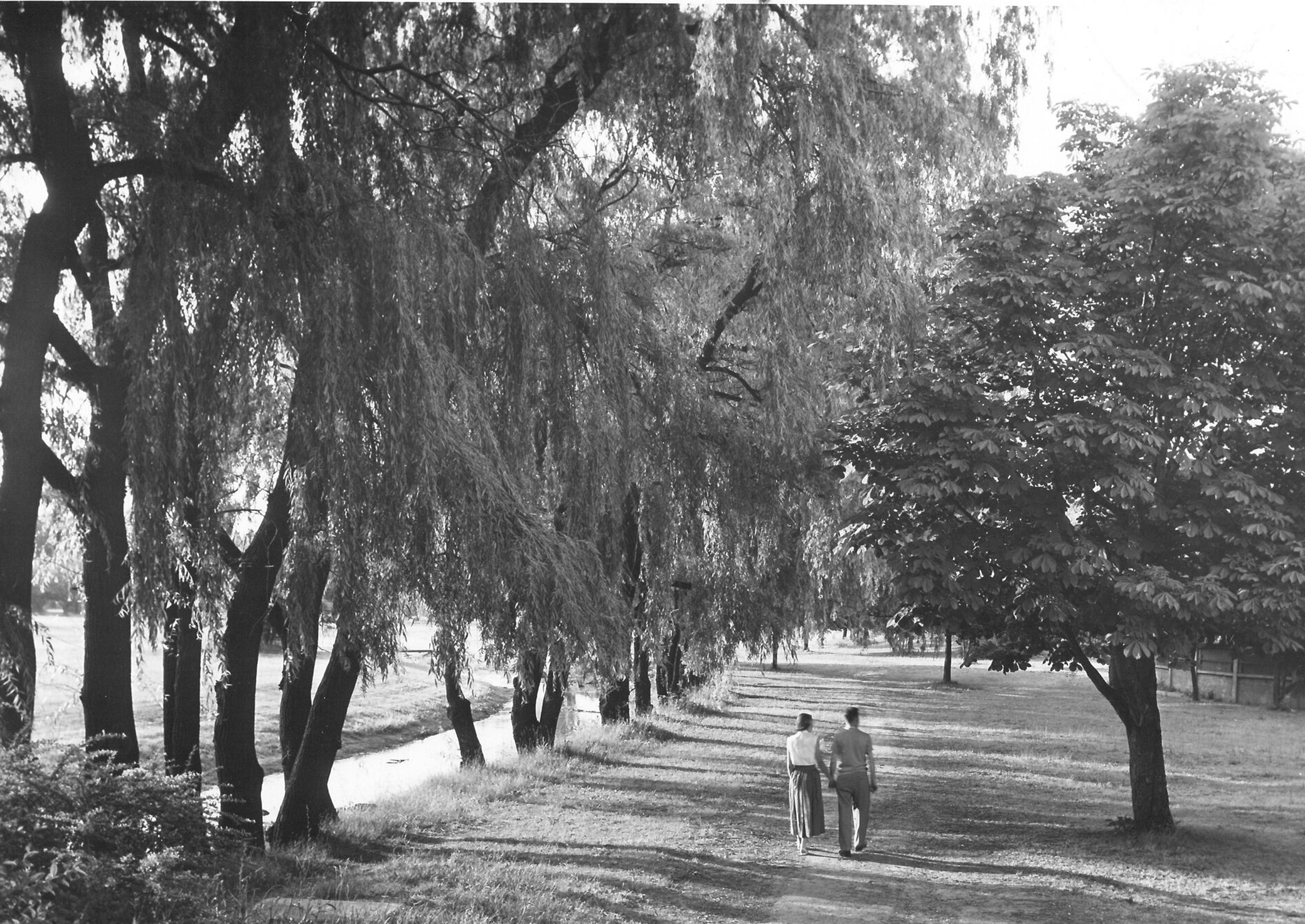

Looking through the photo archives of Flint’s parks and recreation department, I was struck by how water had such a rich place in the city’s history. Flint, the birthplace of General Motors, is famous as an industrial hub. But it is also a river town, only seventy miles away from both Saginaw Bay and Lake Huron. It’s part of the Great Lakes ecosystem, one of the most abundant sources of freshwater on the face of the earth.

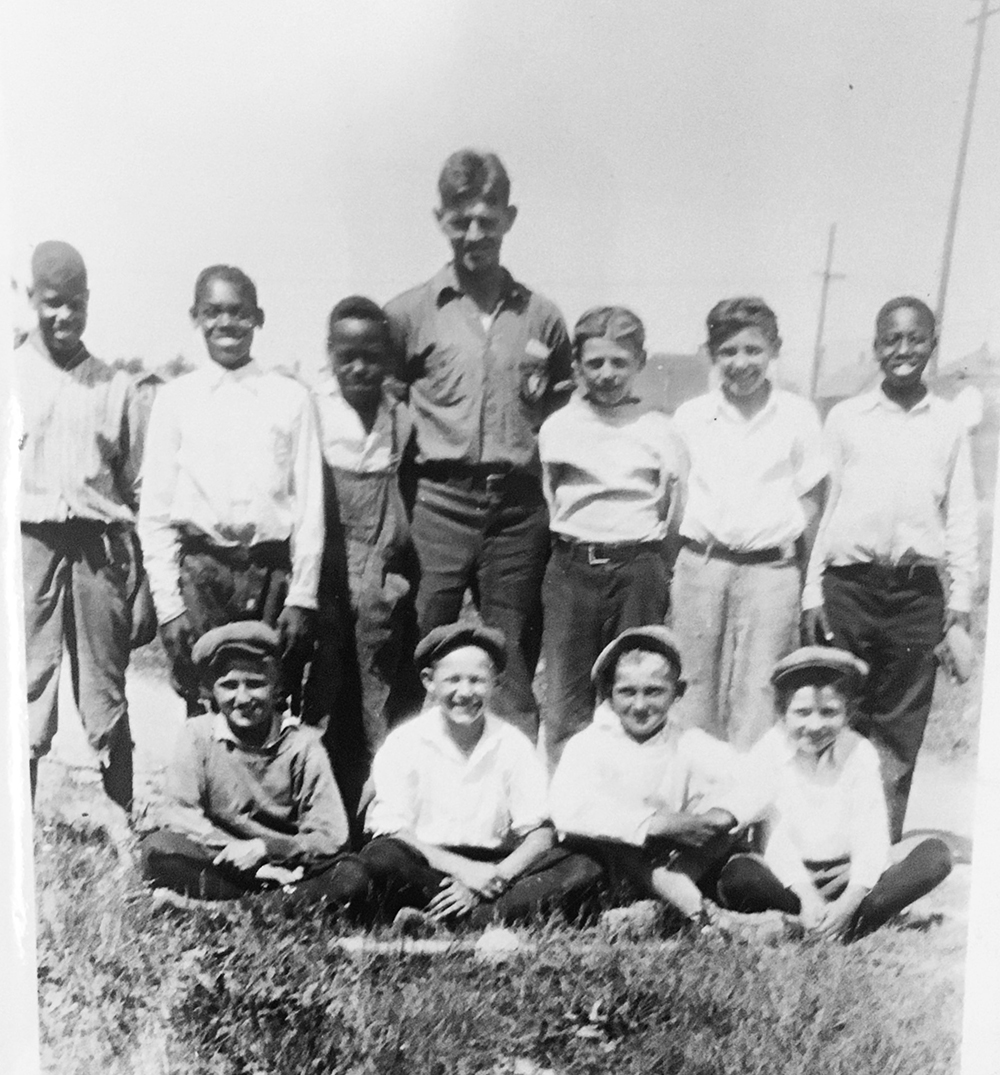

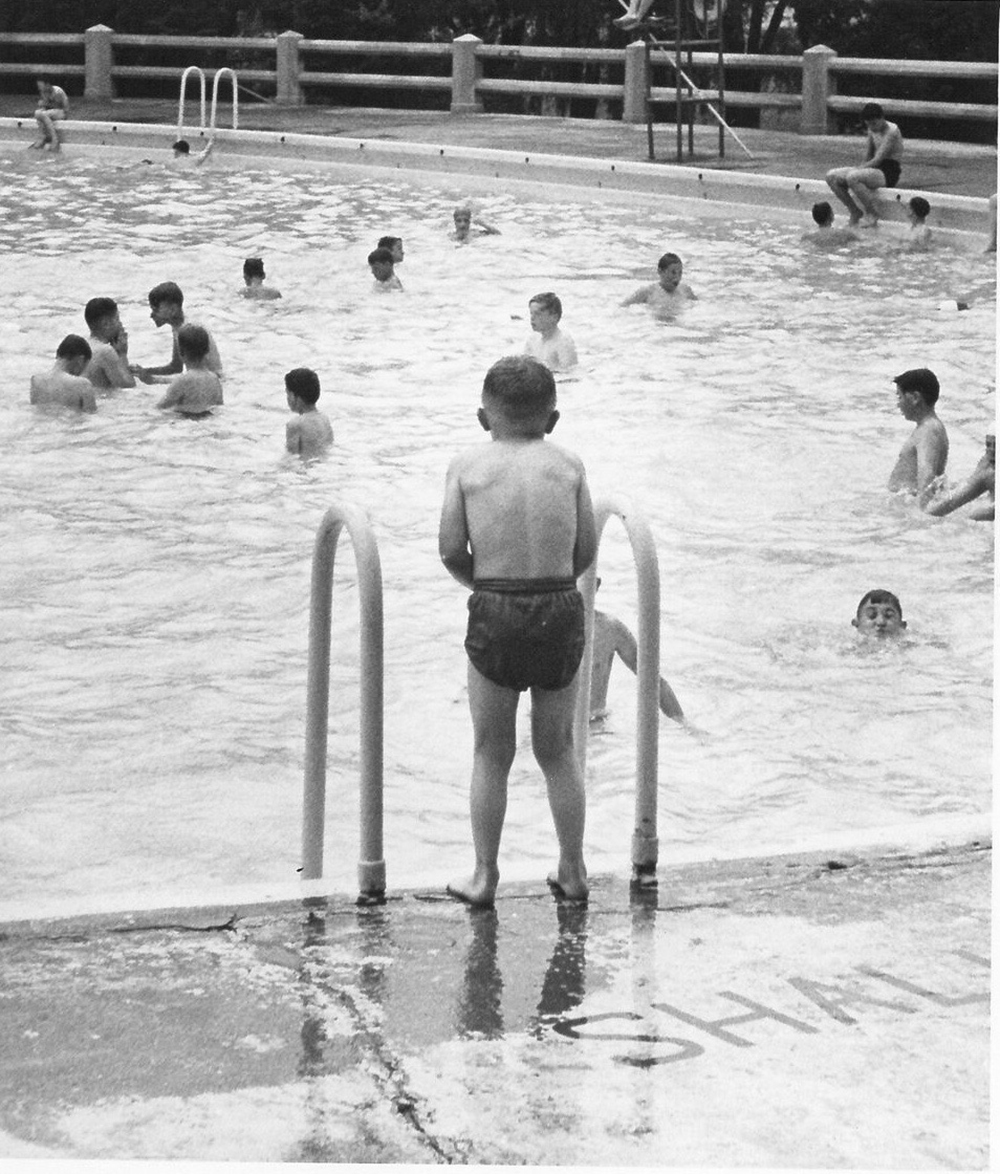

In one photograph after another, I saw the people of Flint gathering along riversides, pools, and reservoirs. The waterways built community—sort of. The photos were also revealing in what they didn’t show. Flint was the most segregated city in the North, and the third most segregated city nationwide. I found a 1929 photo of an integrated children’s baseball team—the league champs, according to the handwriting on the back. But in later years, when the African American population in Flint exploded, they vanished from many community spaces and from, it seemed, the photographic record. At Berston Field House, white children played in the pool while African American children were set up with sprinklers. Black children could swim in the Berston pool once a week, and afterward the pool was drained and cleaned before white children returned.

This divisiveness, plus decades of mistreatment of the Flint River—it was polluted, dammed, and channeled—ultimately alienated the community from its water. Pools closed. The river was scorned, even as deindustrialization and environmental regulations helped to heal it. And then came the Flint water crisis.

For years, the volunteer-powered Flint River Watershed Coalition has nurtured a new vision for the city and its river. Director Rebecca Fedewa told me that at the height of the water crisis, when the river itself was blamed, rather than the decision-makers who mishandled it, she feared that their work would take a catastrophic hit. Who could ever love the river now?

But in fact more people than ever showed up to their programming: paddles and cleanups and bike rides on the river trail. The crisis made people curious. They wanted to see for themselves. Maybe, with time, the water that flows across borders, through the city, the suburbs, and outlying rural areas, will not be used to separate people, but to bring them together.

Read more on Water in the Summer 2018 issue of Lapham’s Quarterly.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Jeff Biggers, author of Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Alastair Bonnett, author of Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Stuart Kells, author of The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing