Knitting in the Library, by Mary Cassatt, c. 1881. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1919.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Stuart Kells, author of The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders, out now from Counterpoint Press.

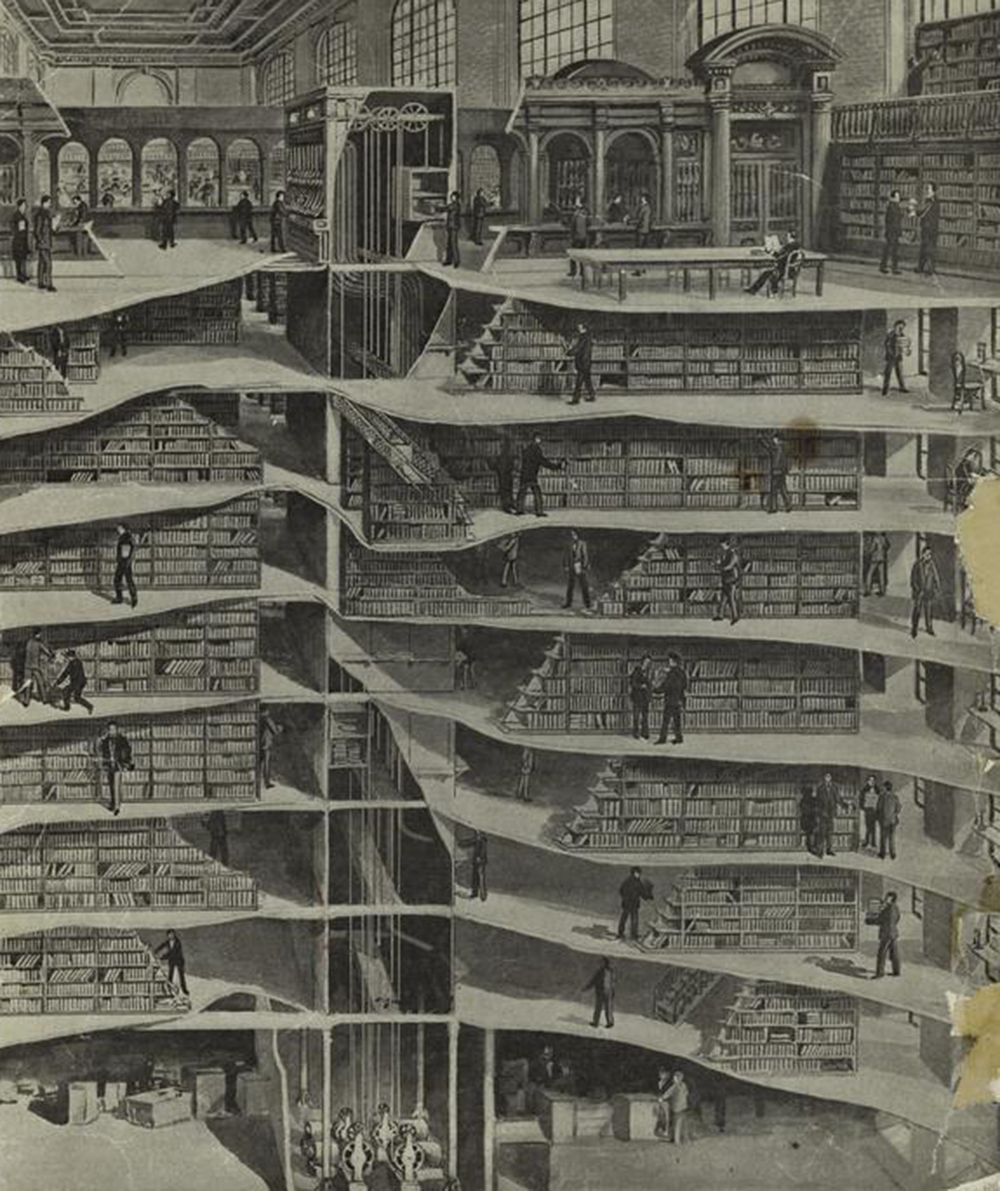

On a recent tour of great libraries, I encountered spaces and pages that told pungent truths about the past. But when the time came to write about the libraries, the most useful source text was a work of fiction. Real libraries, it turns out, have rich and reciprocal relationships with fanciful ones.

The most fanciful library ever imagined is the endless labyrinth of Jorge Luis Borges’ “Library of Babel.” In that story, the universe is a honeycomb of hexagonal rooms containing an infinity of books with a standardized format but randomized contents. This fantastical vision was grounded in the most mundane reality: Borges’ dead-end job of cataloguing books at a municipal library. J.R.R. Tolkien’s Middle Earth is another fantastical vision: a land of dragons, dwarves, and elves. Paradoxically, though, Middle Earth’s many libraries are fastidiously plausible. Elias Canetti’s 1935 novel, Auto-da-Fé, is set in a very different world, but there are dwarves again—along with pickpockets, hustlers, and murderers. The novel metaphorically reimagines the tragic end of the most famous ancient library: the Great Library of Alexandria. The history of that library is a muddle of contradictory facts and myths. Its true story remains to be told.

Composed over the better part of a decade, Umberto Eco’s novel The Name of the Rose blends fantasy and reality in spectacular fashion. Like Borges, Eco was a master of intertextual connections and verbal play. Like Tolkien, he was a formidable medievalist. (When interviewed about his novel, he remarked: “I know the present only through the television screen, whereas I have direct knowledge of the Middle Ages.”) The novel had multiple inspirations. A nineteenth-century book on poisons, found at a bookstall on the Seine. Real libraries, too, and real manuscripts, such as the oldest extant plan of a monastery. That plan is the treasure of St. Gall, Switzerland. Only one part of it was ever built: the library, a perfect cube.

The core of Eco’s book, and the fulcrum for its plot, is the most remarkable library ever captured in words:

the place of a long, centuries-old murmuring, an imperceptible dialogue between one parchment and another, a living thing, a receptacle of powers not to be ruled by a human mind, a treasure of secrets emanated by many minds, surviving the death of those who had produced them or had been their conveyors.

St. Gall’s cube influenced the monolithic and geometric design of Eco’s library, as did Borges’ hexagons. Borges is also present in the library in the person of the blind librarian, “Jorge from Burgos.” Alexandria is there, too; the library ends in fire.

A hub in a web of texts, Eco’s novel blends traditions as diverse as classical philology, heterodox theology, and the English detective story. It is an all-encompassing essay on the power and danger of books, and on their radical, fractal nature. And it is a hymn to the enduring wonder and potent magic of libraries.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Sarah Henstra, author of The Red Word

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing

• Louise W. Knight, author of a forthcoming book on the Grimké sisters

• Roxanne Dunbar Ortiz, author of Loaded: A Disarming History of the Second Amendment

• Fiona Sampson, author of In Search of Mary Shelley: The Girl Who Wrote Frankenstein