La Lecture, by Norbert Goeneutte, c. 1880. The British Museum, Prints and Drawings.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Emily Midorikawa and Emma Claire Sweeney, authors of A Secret Sisterhood: The Literary Friendships of Jane Austen, Charlotte Brontë, George Eliot, and Virginia Woolf.

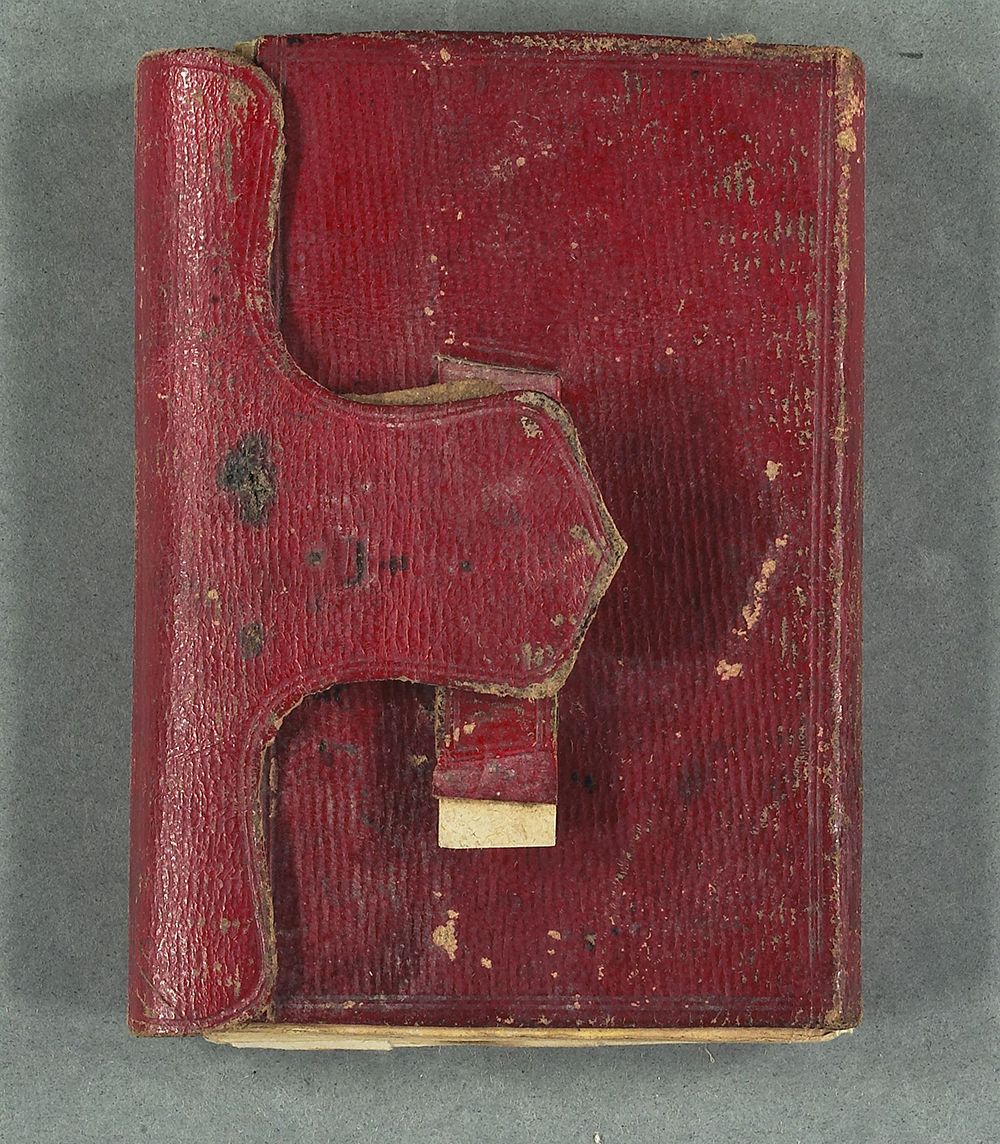

Between them, Jane Austen’s sister and niece destroyed most of her letters, leaving generations of readers wondering what the novelist’s family might have felt so compelled to hide. Miraculously, however, the pocketbooks of Jane’s niece escaped the cull. These crimson calfskin diaries—in which Fanny made meticulous entries from the age of ten—have been passed down to us unscathed. Stowed deep in an archive in rural Britain, this stash of pocketbooks remains curiously unmined by literary critics. These pages reveal intriguing details of Jane’s friendship with a mysterious woman named Anne Sharp, who sustained the Pride and Prejudice author both in her struggle towards publication and during the high points of her writing career.

Anne, an amateur playwright, was employed as the governess of young Fanny. This unlikely bond between Jane and a member of Austen domiciliary staff calls into question the family’s portrayal of their famous relative as a lady scribbler whose refined acquaintances “constituted the very class from which she took her imaginary characters.”

Sadly, Anne’s scripts have been lost to history. But Fanny’s diaries reveal that during the new year celebrations of 1806, Anne rehearsed a series of plays and monologues in the Austen household. In between carol singing, treats of Spanish liquorice, and games of snapdragon, apple bobbing, and blind man’s bluff, she prepared the children for a festive performance.

In the small space her diaries allowed for reports of each day, Fanny mentioned that she had made a detailed description of Anne’s theatricals on separate pieces of paper. These supplementary documents are absent from any library records, and, when we mentioned them to archivists, we were told that they must not have survived.

But, in fact, hidden within Fanny’s 1806 diary, we discovered a secret pouch, its card as brittle as late autumn leaves. The glue that had originally attached it to the inside covers had long lost its grip, but tucked inside was an account of Anne’s theatricals—hidden there for well over two hundred years.

These descriptions of Anne’s play, Pride Punished or Innocence Rewarded (named before Jane changed the title of her most famous novel from First Impressions to Pride and Prejudice) allow us to eavesdrop on Anne—the woman on whom the great Jane Austen always relied for candid feedback, an unknown female writer whose voice had, until now, been all but lost.