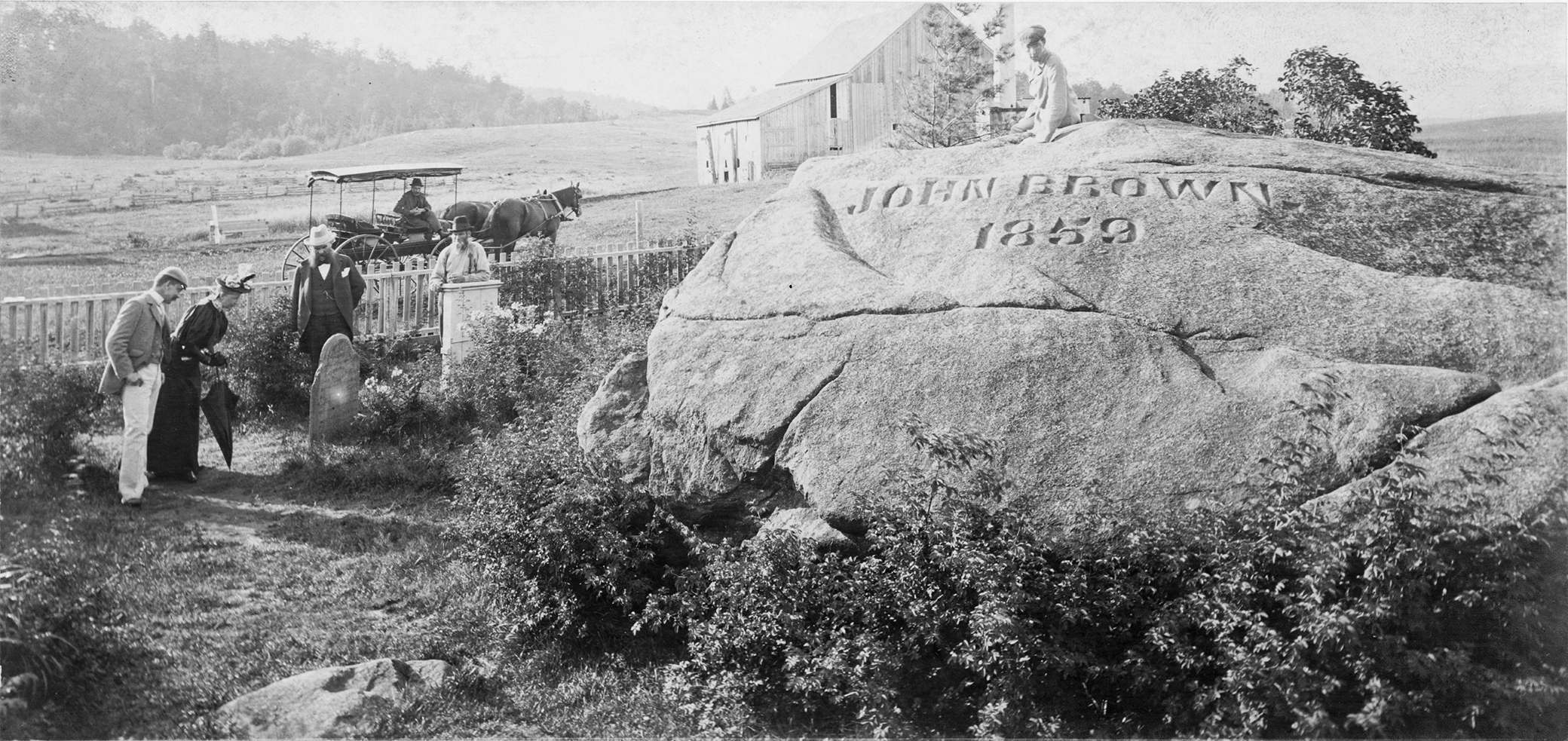

John Brown’s grave and the “Big Rock,” North Elba, New York, c. 1896. Photograph by Seneca Ray Stoddard. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent.

When John Brown moved to the Great Northern Wilderness of New York State—a place we now call the Adirondack Park—he hadn’t yet committed the 1856 murders of five proslavery Kansans that would catapult him to fame. He hadn’t staged his 1859 assault on the arsenal at Harper’s Ferry. And he hadn’t been hanged for treason, murder, and inciting slave rebellion. In 1849 John Brown was neither martyr nor madman; he was just a footnote, a recently failed farmer and wool merchant who came to the Adirondacks looking for Timbuctoo.

The American Timbuctoo was a community of black abolitionists who sought a complete social and economic transformation of the United States. It has now been all but forgotten, but, in the decade immediately preceding the Civil War, Timbuctoo was a well-known radical experiment in land redistribution, agrarianism, and nonviolent civil liberation.

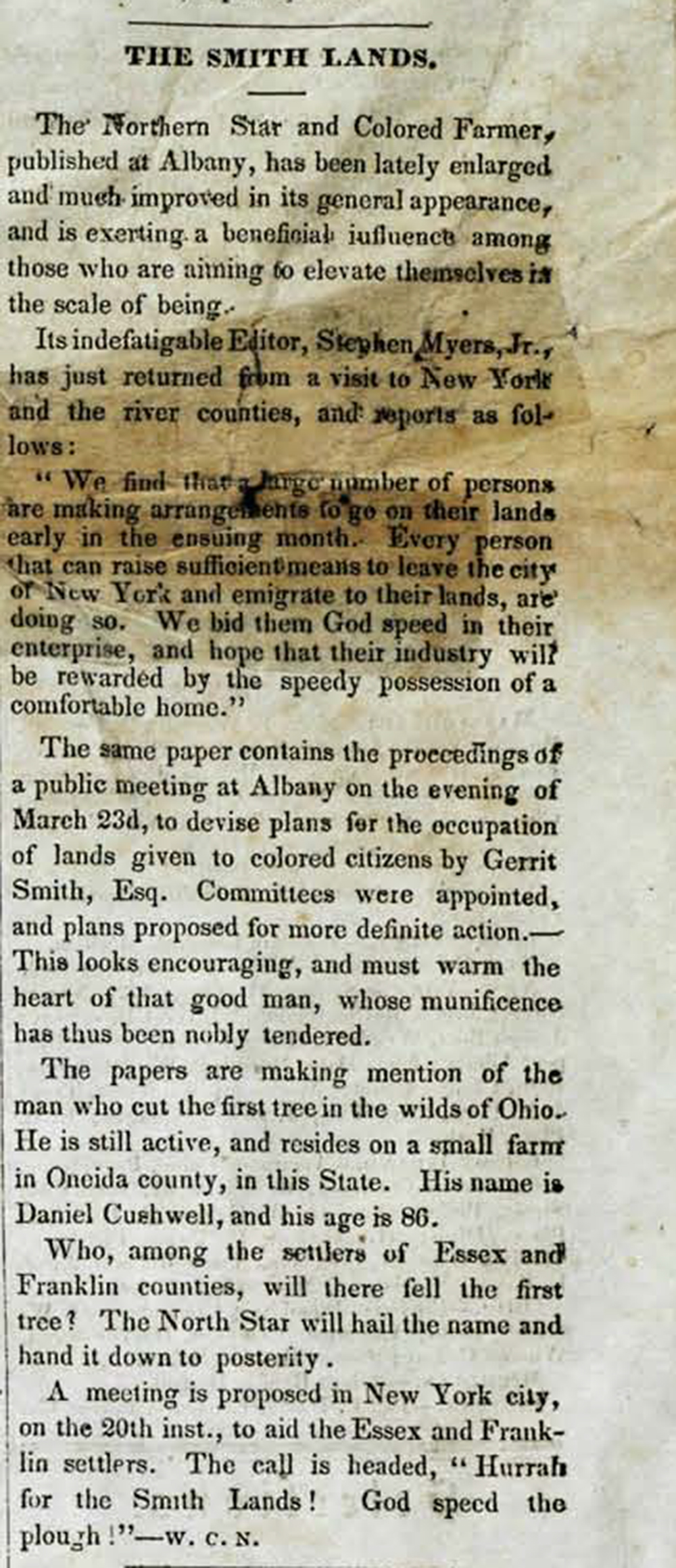

Timbuctoo hatched from the wallet of the wealthy white abolitionist Gerrit Smith. In 1846 he gave 120,000 acres of his Adirondack land to three thousand African American New Yorkers, but it was really his black abolitionist comrades—chief among them the doctor, writer, and anti-racist theorist James McCune Smith—whose care nursed the community to health. Though never more than a few score families settled this land, the venture drew intense interest from across the abolitionist universe. It even had the support of Frederick Douglass, whose newspaper, The North Star, profiled Timbuctoo numerous times between 1848 and 1860.

But neither Brown nor the community would survive the all-consuming violence of war. Once Brown’s body was cut down from the gallows pole, it was sent back north, to his Adirondack homestead, and laid to rest near the Big Rock that would come to be his tombstone. And the black settlers—bereft of abolitionist support—trickled back to wherever they had lived before coming to Timbuctoo.

Below is a letter from James McCune Smith to Gerrit Smith. McCune Smith was touring the Adirondack settlements, and he spent some time at his own forty-acre plot. You can still visit Timbuctoo, which is now a forested part of the High Peaks Wilderness Area, as well as John Brown’s homestead, which, more than a century and a half later, now sits in the shadow of an Olympic ski jump complex.

In September last…I visited Essex & Franklin Counties…

We found in North Elba about sixty colored persons in all, of all ages and sex. As a general thing the parties has not enough money at the outset, and had failed in making up the deficiency partly from the backwardness of the season and partly from having waited too long for Mr. John Brown’s team. They were however cheerful, many of them hardy and industrious: a fine talk they made too, about their feeling of independence, when I fear they were a little too dependent upon Mr. Brown’s meal bin. They had put up several good log houses, and I suppose by this time have made a pretty fair [illegible]. What struck me most was the evident impulse the old settlers had received: I think more clearing has been done within a year…then in any three years together of late…

I felt myself a “lad indeed” beneath the lofty spruce and maple and birches, and by the baubling brook, which your deed made mine, and would gladly exchange this bustling anxious life for the repose of that majestic country, could I see the day clear for a livelihood for myself and family. I am not afraid of physical labor: but do not think it would be prudent to risk sustenance in my [illegible] labor in the farming line: and the country is yet too sparse to give support to a physician. Unless therefore, and until, I can make enough to secure an income of $400 per annum, I must defer settling in Essex County.

As we went north thro’ township 11 and 10, we found (over a superbly rough stump and corduroy road) here and there colored settlers making their woods ring with the music of their axe strokes; of course we broke down, got lost in the woods, and became deeply indebted to Mr——— of lot 204 To 10 for assistance and direction…

To return to Township 12. Mr Henderson, a shoe-maker from Troy, has his sign hanging out (the first and only in the township) and appeared to do a good business. Mr. [illegible] had cleared about two acres…Could we get about 200 settlers in North Elba, and then cut off all communication with the city (burn the galleys) things could be made to prosper.