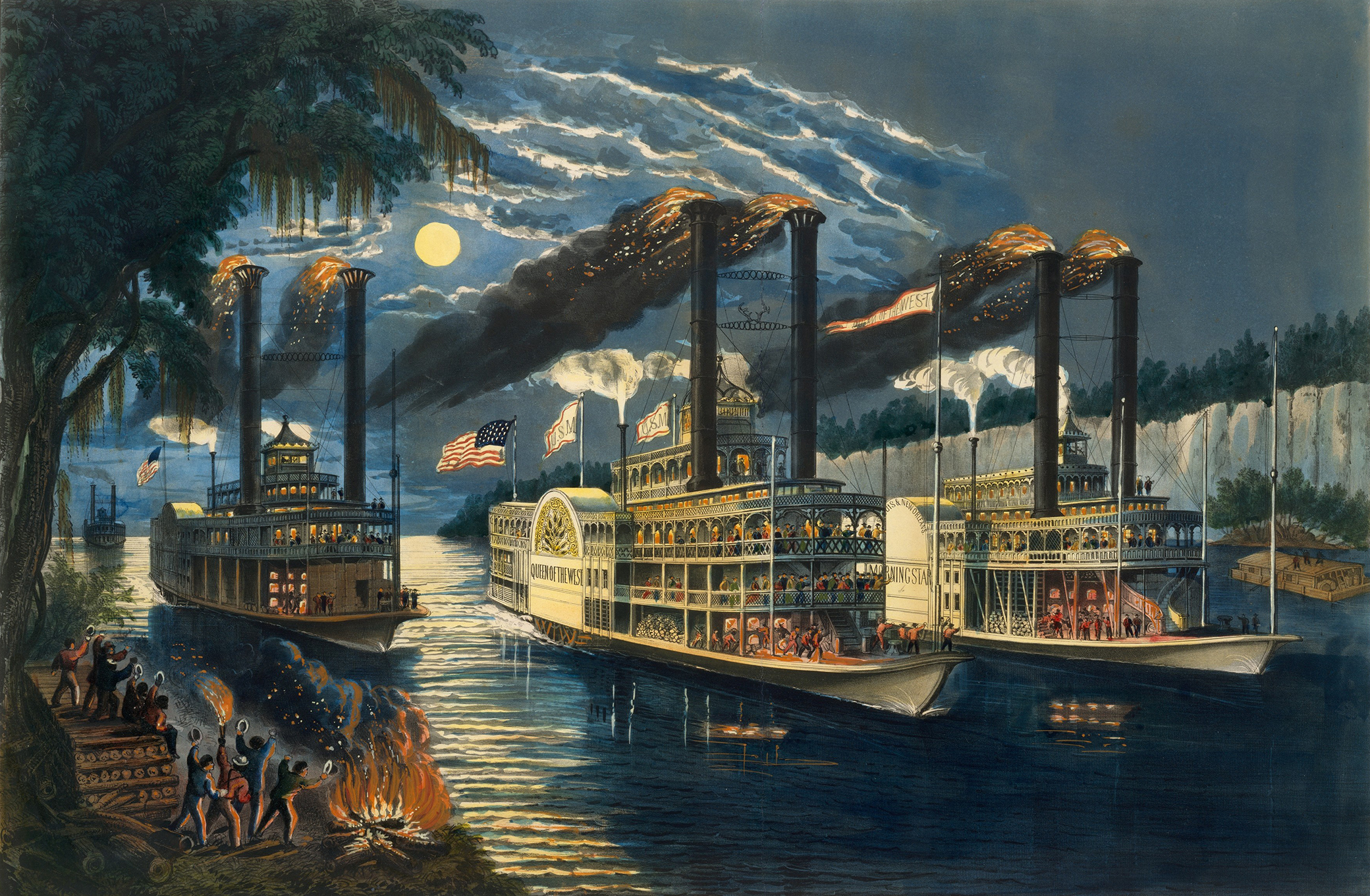

The Champions of the Mississippi, by Frances Flora Bond Palmer, 1866. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Adele S. Colgate, 1962.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America, out now from Basic Books.

Two intriguing aspects of my research for The Fair Chase concerned sport hunting’s persistence as a subject for both fine and decorative arts in the nineteenth century and the influence of women on the hunt—from the trick-shooting prodigy Annie Oakley to Martha Maxwell, the “Colorado Huntress,” whose dioramas of taxidermy were a crowd favorite at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia.

Another fascinating figure was the gifted illustrator and lithographer Frances Flora Bond Palmer, considered the first woman to make a living as an artist in America. Fanny, as she was known, and her husband Edmund, a printer, started in England as commercial illustrators of monuments, churches, farms, and railway viaducts—her efforts were hailed by one critic for “a boldness and freedom not often exhibited by a female pencil.” In 1844 the couple moved to New York to expand their business but met entrenched competition. Edmund opened a tavern in Brooklyn while Fanny tried her hand at everything from giving singing lessons to serving as a governess. She eventually resumed her artistic career, obtaining work with printer Nathaniel Currier.

Sporting scenes of hunting became a specialty (Edmund and his dogs served as her models). She also drew trains, tableaux of gardens, rustic homes, scenes of westward expansion, majestic river views, and young people in sleighs or ice skating—popular (and now iconic) images of a dynamic, confident America at mid-century. Her work’s high quality was likely due to the fact that she was both artist and lithographer, and thus able to ensure the most accurate renderings. “From nature and on stone,” she would sign those works she herself had sketched from life (or sometimes simply “F.F. Palmer”); however, her most recognized work, A Midnight Race on the Mississippi, the depiction of the legendary 1854 race between the steamboats Natchez and Eclipse, was based on news accounts.

Edmund died in 1859, apparently after an inebriated tumble down a flight of stairs. Fanny, who needed to support a sickly son and a daughter who was a young widowed mother, intensified her efforts for Currier, who had now been joined by a partner, James Ives. She ultimately produced about two hundred prints for the firm of Currier & Ives, more than any other single artist. Although alone of her sex in an industry in which largely anonymous artists created art intended chiefly to be ornamental, she has long been relatively unknown. “It is likely,” concludes one historian, “that during the latter half of the nineteenth century more pictures by Mrs. Fanny Palmer decorated the homes of ordinary Americans than those of any other artist, living or dead.”

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Stuart Kells, author of The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Sarah Henstra, author of The Red Word

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing

• Louise W. Knight, author of a forthcoming book on the Grimké sisters