Susan B. Anthony sitting and reading a book, c. 1900. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Sander L. Gilman author of Stand Up Straight! A History of Posture, out now from the University of Chicago Press.

We demand of our children, our students, and secretly of ourselves that they and we “Stand Up Straight!” This is as much a moral imperative as a demand that we fulfill the expectations of our society in the way we sit and stand. Be upright and don’t simply posture, we say, act morally not hypocritically. All societies have systems of posture: how to stand when addressing the leader, how you sit at meals, formal and informal, and what arrangement your limbs take when you walk, march, or dance. These are also signs of our moral lives, but do they reveal them or mask them?

In my book, I trace the Western history of the upright body at rest and in movement, from the way we imagined how our tangential ancestors the Neanderthals stood to how we continue to use our understanding of posture to define who we are—and who we are not. Traversing theology and anthropology, medicine and politics, from discarded ideas of race and the most modern ideas of disability, theories of dance and concepts of national identity, I try to show how our posture informs or disguises not only who we are but essentially also who we are not! Our bodies are not fixed. They expand and contract with variations in diet, exercise, and illness. They alter as we age, changing over time to be markedly different at the end of our lives from what they were at birth.

In a similar way, our attitudes to bodies, and especially posture—how people hold themselves, how they move—are fluid. We interpret stance and gait as healthy or ill, able or disabled, elegant or slovenly, beautiful or ugly. The history of posture means seeing bodies as we imagine them, not as they are. Thus the history is fully illustrated with an array of striking images from medical, historical, and cultural sources illustrating our changing attitudes toward stiff spines, square shoulders, and flat tummies through time.

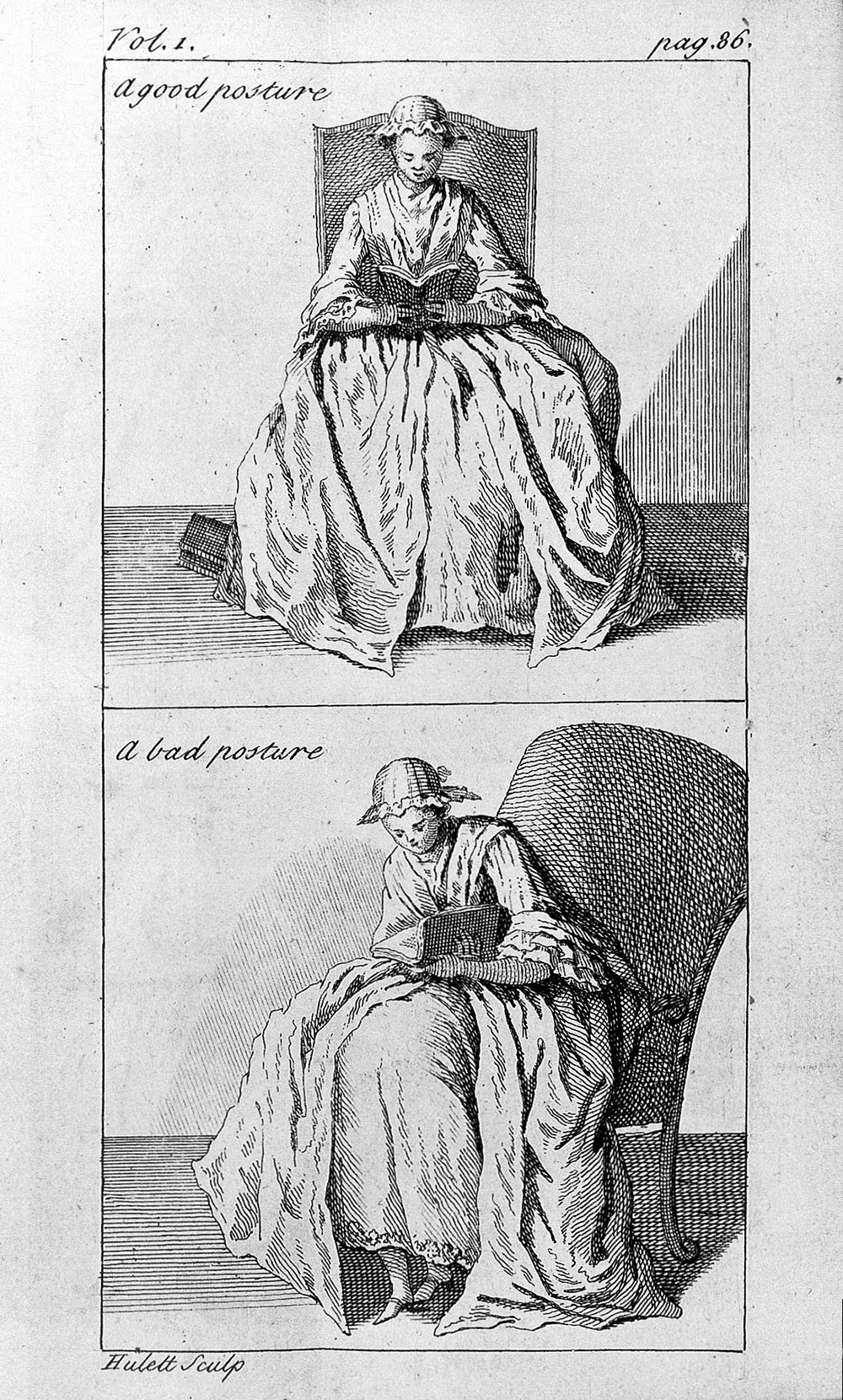

Reading my history of posture means being self-conscious even about our posture as readers. In 1741 the aged former dean of the Faculty of Medicine at Paris, Nicolas Andry de Bois-Regard, then eighty-two, published what comes to be the first exhaustive account of correcting posture, his L’orthopédie ou l’art de prévenir et corriger dans les enfants les difformités du corps. He argues that most of man’s ills were caused by the poor posture he developed in childhood, including our stance while reading.

Are you reading in a correct posture? Perhaps you should, given our recent fascination with standing desk, be standing? But even that act of standing to read has an ancient pedigree reaching back to the dark ages.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Alastair Bonnett, author of Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

• Scott Samuelson, author of Seven Ways of Looking at Pointless Suffering

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Stuart Kells, author of The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Sarah Henstra, author of The Red Word

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing