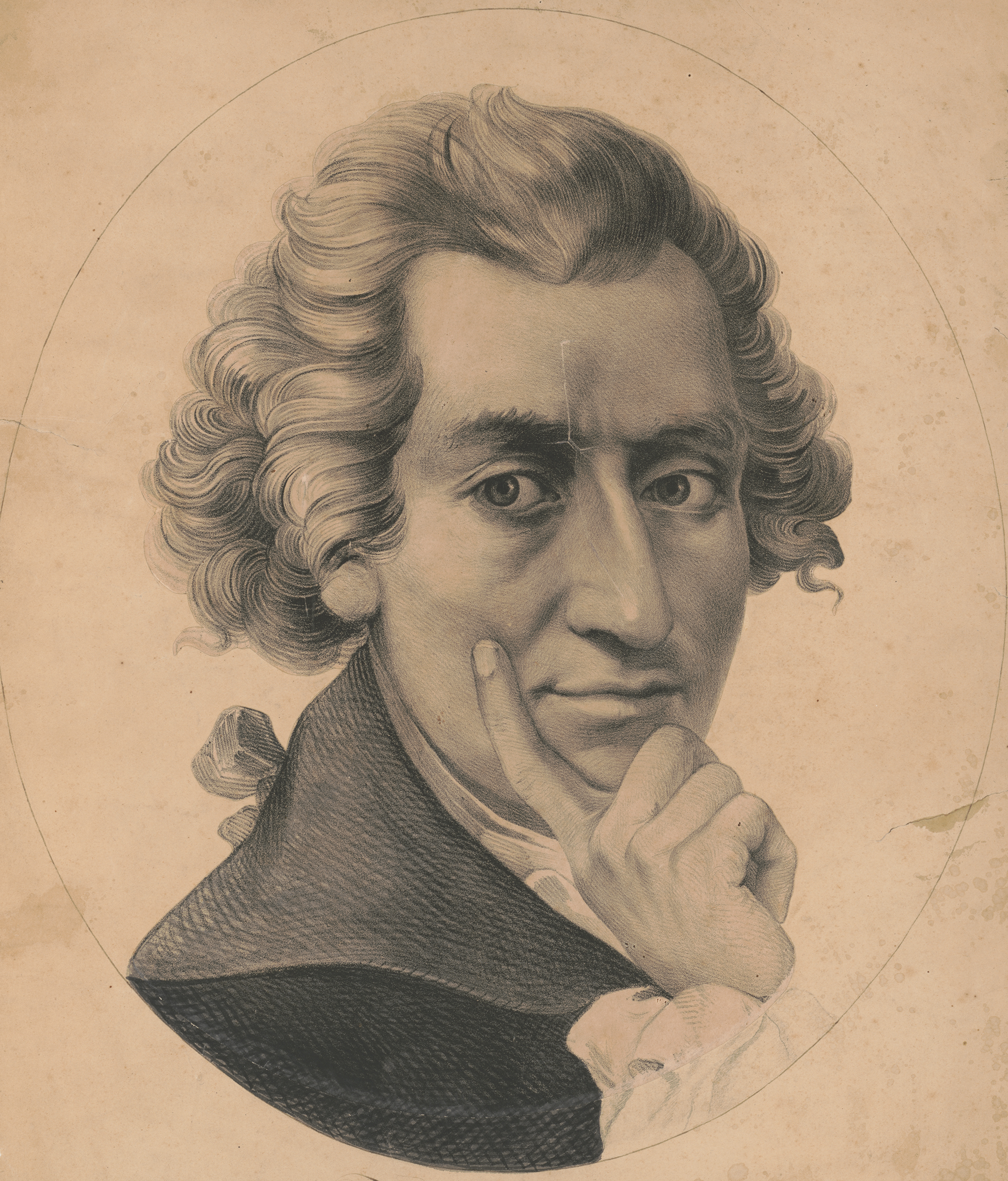

Thomas Paine, by Peter Kramer, c. 1851. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Jeff Biggers, author of Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition, out now from Counterpoint Press.

In 1782, as peace negotiations began in Paris between representatives of the United States and the British Crown, Thomas Paine sat down to write a response to the Abbé Raynal in France, who had published his own long-distance narrative of the American Revolution. Anguished that the Frenchman had reduced the “justifiable resistance” to a nationalistic spat over tea and taxes, Paine characterized his letter as one “in which the Mistakes in the Abbé’s Account of the Revolution of America are Corrected and Cleared Up.”

A letter from Paine was no small event. He may have once identified himself as the secretary in the Foreign Department of Congress, but Paine’s numerous revolutionary pamphlets, such as Common Sense, had ensured his legacy as the literary instigator of the American resistance. The very name of our nation—the United States of America—first appeared in Paine’s handwriting. He was the nation’s most widely read author—though not its bestselling one. While all of Paine’s works went viral, in modern terms, none put a single penny in his pocket: they were freely distributed. Even the envious founding father John Adams bitterly admitted to Thomas Jefferson, “History is to ascribe the American Revolution to Thomas Paine.”

In Paris, an American traveler reported, Paine’s translated work was “everywhere.” His Letter to the Abbé Raynal had “sealed his fame,” the traveler added. “Even those who are jealous of, and envy him, acknowledge that the point of his pen has been as formidable in politics as the point of the sword in the field.”

Far from being an armchair revolutionary, Paine had insisted on taking a role on the front lines. “As I was with the troops at Fort Lee, and marched with them to the edge of Pennsylvania, I am well acquainted with many circumstances, which those who live at a distance know but little or nothing of,” he had written from the camps of George Washington’s Revolutionary forces.

But the misinformation about military tactics and strategies did not interest Paine now. His letter to the abbé sought to define the transformative impact of the resistance movement on Americans in the aftershock of their triumph. “Our style and manner of thinking have undergone a revolution more extraordinary than the political revolution of the country,” he explained to the French. “We see with other eyes; we hear with other ears; and think with other thoughts, than those we formerly used. We can look back on our own prejudices, as if they had been the prejudices of other people. We now see and know they were prejudices and nothing else; and, relieved from their shackles, enjoy a freedom of mind, we felt not before.”

High-minded perhaps, but hardly delusional, Paine claimed this new way of thinking had “opened itself toward the world” and brought Americans into the world of nations. He didn’t trumpet the military triumph of Washington and his French allies; nor did Paine make an inventory of the natural resources and wealth now at American disposal. The future of the United States of America—and consequently the world—rested in the hands of “science, the partisan of no country, but the beneficent patroness of all,” which served as the great “temple where all may meet.”

Paine’s message to the abbé reflected the ongoing negotiations in Paris—and a clear admonition to its leaders. Instead of pursuing that “temper of arrogance,” he warned, “which serves only to sink” a country in esteem and to “entail the dislike of all nations,” Paine called on all leaders to find a way for the world to live in peace.

Here's an excerpt from the letter:

Letters, the tongue of the world, have in some measure brought all mankind acquainted, and by an extension of their uses are every day promoting some new friendship. Through them distant nations became capable of conversation, and losing by degrees the awkwardness of strangers, and the moroseness of suspicion, they learn to know and understand each other. Science, the partisan of no country, but the beneficent patroness of all, has liberally opened a temple where all may meet. Her influence on the mind, like the sun on the chilled earth, has long been preparing it for higher cultivation and further improvement. The philosopher of one country sees not an enemy in the philosopher of another: he takes his seat in the temple of science, and asks not who sits beside him.

From Resistance: Reclaiming an American Tradition. Used with permission of Counterpoint Press. Copyright © 2018 by Jeff Biggers.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Sander L. Gilman, author of Stand Up Straight! A History of Posture

• Alastair Bonnett, author of Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Stuart Kells, author of The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing