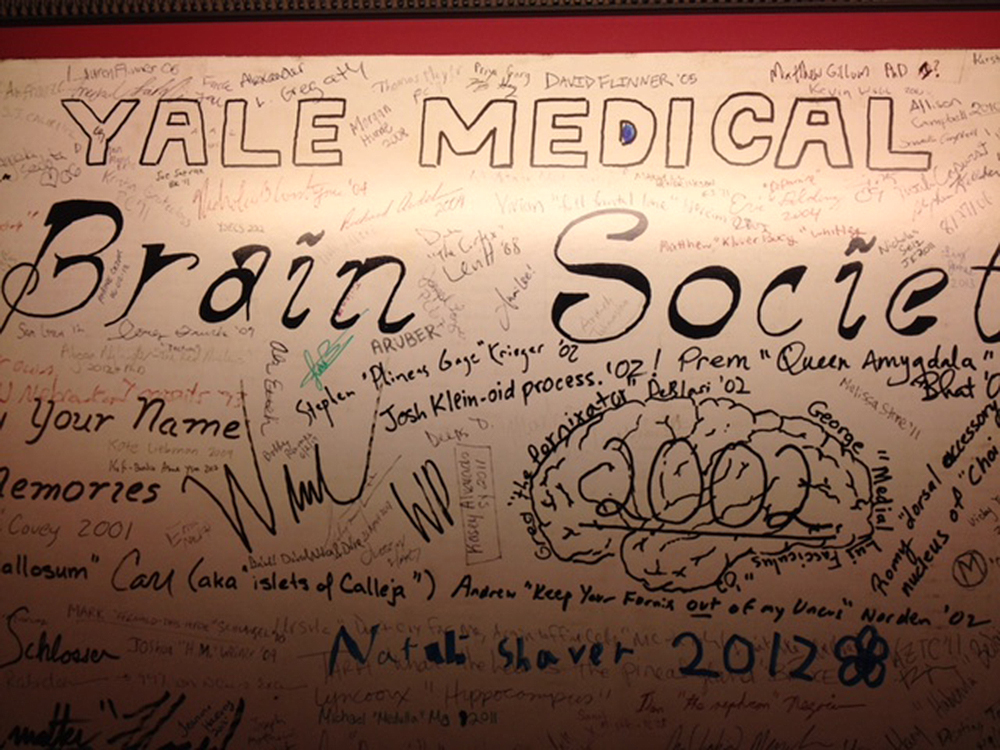

Brains stored in a college dorm basement at Yale Medical School. Photograph by Terry Dagradi.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Randi Hutter Epstein, author of Aroused: The History of Hormones and How They Control Just About Everything, out now from W.W. Norton.

From 1906 through 1932, Dr. Harvey Cushing, a founder of the fields of neurosurgery and endocrinology, collected brains from his patients and stored them in jars. Sometimes he took a tiny piece of a tumor retrieved during surgery, sometimes a large chunk. Often he’d get the rest of the brain after the patient died. Eventually he amassed more than 660 jars.

For years after Cushing’s death in 1939, these jars were stacked in the basement of the dorms at Yale Medical School. During the 1990s, it became a rite of passage for students to sneak down and see the creepy collection. There you could sign a poster labeled “Brain Society.” The club didn’t do anything except provide bragging rights.

Today, thanks to a massive renovation effort, 550 of the jarred brains have been restored and are now displayed in the Cushing Center, two floors below the main reading level of the Cushing/Whitney Medical Library at Yale University. These pickled brains—along with Dr. Cushing’s medical sketches, his photographs of patients, and other medical paraphernalia—provide a unique view into the earliest days of hormone research, one in which Cushing proposed a theory connecting mind and body. His research helped to catapult endocrinology from an inchoate science into a flourishing profession.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Sander L. Gilman, author of Stand Up Straight! A History of Posture

• Alastair Bonnett, author of Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Stuart Kells, author of The Library: A Catalogue of Wonders

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing