Norwegians Land in Iceland in 872, by Oscar Wergeland, 1877. National Gallery of Norway, The Fine Arts Collections.

There are some forty “sagas of Icelanders,” and close on fifty þǽttir, or short stories about Icelanders, but of them all only one gives a full and plausible picture of a Viking hero—that is, one who makes his reputation and does his most famous deeds outside Iceland, in Scandinavia itself and in the raiding grounds of the British Isles. Most Icelandic heroes are essentially homebodies. Their sagas may contain some dreamed-up adventures abroad, in which they show up the Norwegians and compensate for the Icelandic colonists’ “cultural cringe.” But they then come home to become involved in the main events of their lives as described in their sagas, which is fighting with their relatives and neighbors.

The exception to the rule is Egils saga Skallagrímssonar, “The Saga of Egil Skallagrimsson,” or Egil’s Saga for short. This brings its hero, with some of his friends and enemies, into the relatively well-recorded milieu of Anglo-Saxon England during the Viking wars of the mid-tenth century. But even more important than the saga’s relative historical verifiability is the fact that Egil shows the dark as well as the admirable side of the Viking ethic better and in more detail than any other. He was mean, in every sense of the word: so mean even the other Vikings noticed.

This did not prevent him from being also the greatest named poet, or skald, of the Viking world. Viking poetry was not a matter of daffodils and nightingales and soulful private epiphanies.

But what made him so mean?

Egil’s Saga describes him physically like this:

He sat upright, but with his head bowed low. Egil had very distinctive features, with a wide forehead, bushy brows, and a nose that was not long but extremely broad. His beard grew over a long, wide part of his face, and his chin and entire jaw were exceptionally thick. With his thick neck and broad shoulders, he stood out from other men. When he was angry, his face grew harsh and fierce. He was well built and taller than other men, with thick wolf-gray hair, although he had gone bald at an early age.

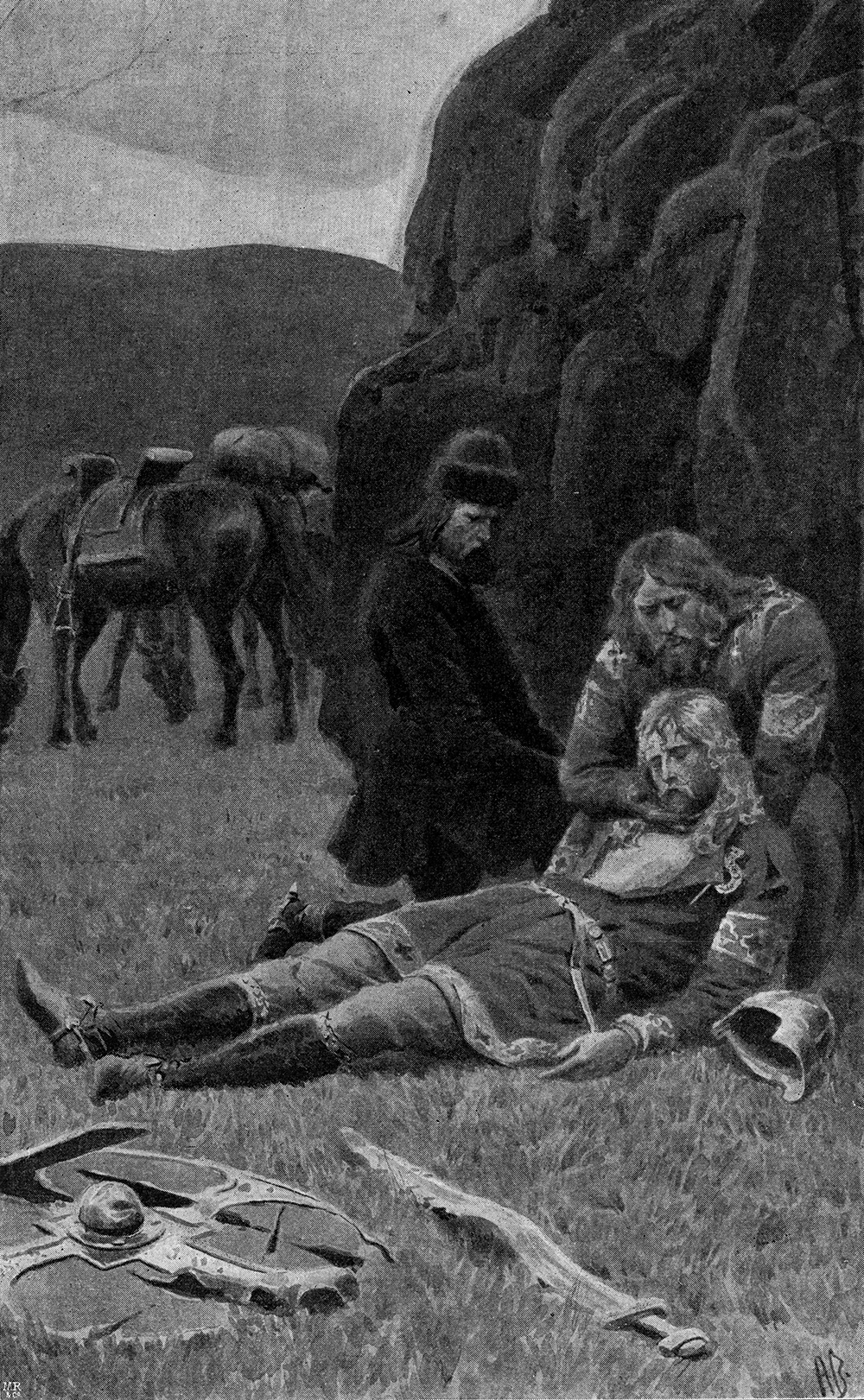

The description comes from a moment just after Egil has (according to the saga) won a vital battle for the English king Athelstan, at the cost of his brother Thorolf, who is not only Egil’s brother but also something like his minder: the sensible one who can keep his dangerously unpredictable brother under partial control. As he sits at the victory feast, Egil puts his sword across his knees and starts half-drawing it, then slamming it back in its sheath. He says nothing amid the merriment, and—very unusually for him—refuses drink, while he “just raised and lowered his eyebrows in turn.” The significance of the last gesture is not at all clear, but it is clear that he is in a temper over something and liable to lash out. King Athelstan sensibly, if silently, draws his sword, puts a large gold ring on it, walks over, and extends it to Egil, who likewise takes it on the point of his sword. He clasps it on his arm, puts down his sword and helmet, takes a drink, stops playing with his eyebrows, and composes an extempore poem.

Athelstan later hands over two chests of silver as payment for Thorolf—there will be trouble over these later—and says some kind words, further mollifying Egil. Sagas very rarely explain what people are thinking, or explain what we are to think about their actions, but it looks as if Egil has been feeling underappreciated, thinking that he has won someone else’s battle at too high a family cost. But is it Athelstan’s recognition or his money that cheers him up? The saga also notes that Egil (again very much unlike his normal behavior) has buried his brother with clothes and weapons and a gold ring on each arm. Was he sulking about losing his brother or losing the gold rings? And did he bury them under pressure from social convention or as a gesture of love and respect, which he then regrets?

Of course, the saga is just a story, written three hundred years after the events in it, and much of it should be considered as a historical novel, not a history. Nevertheless, it does offer a consistent and highly individualized picture: Egil, it tells us, was (1) fierce, (2) poetically talented, (3) greedy for money, and (4) bitter ugly. “Fierce” is common enough for saga heroes, though there are exceptions. There are other sagas about skalds, too, though an unusual amount of poetry said to be composed by Egil has been preserved, and the claims for its authenticity are likely to be true.

Greed for money is more unusual. While the point of raiding is, obviously, to make a good haul, as the sagas often say, what is really respected in most sagas about Icelanders is generosity, readiness to help out—if not with outright gifts of money then with hay or food or assistance in paying compensations. Rich people are good people, because they can afford to be.

But Egil is not like that, and his notorious stinginess is a family trait. Very late in life, his father, Skalla-Grímr—meaning “bald Grim”—suddenly asks his son what happened to the silver King Athelstan gave him. Grim obviously thinks he should have a share of it as payment for the death of his other son. Egil replies evasively, saying he will let his father have money any time he needs it, but “I know you have kept a chest or two aside, full of silver.” After Egil has ridden off on a visit, Grim brings out a large chest and a cauldron and rides off with them. He comes back without them—he is thought to have buried them in a bog—and dies sitting on the edge of his bed.

This is an extreme case of “spending the kids’ inheritance,” as the only fun Grim gets out of it seems to be the knowledge that no one else will get the money, in particular his chiseler of a son. Egil in extreme old age does much the same thing. His first plan, the saga says, was to take Athelstan’s silver to the Lögberg, or “Law Rock” at the Althing, or national assembly, and then throw it into the crowd for the pleasure of seeing the assembly fight for it. When this is vetoed by his son-in-law, also called Grim, who has been looking after him for years, Egil waits until he and his daughter are out of the way and then rides off with the famous two chests, and two slaves to do the digging.

Neither the money nor the slaves come back, and Egil admits freely that he killed the slaves so no one would know where the money was. (People in Iceland are still looking for it in the Mosfell ravine, where old coins have occasionally washed up.) Grim buries his father-in-law, like Thorolf, with his clothes and weapons, but unlike Thorolf, without gold rings. If you spend the kids’ inheritance you must expect a minimal funeral.

Nor does the matter end there, and it was not only the author of Egil’s Saga who knew about the stinginess of the Myramenn family (the Miremen, the Fen-people). In reading Icelandic sagas it is a good rule always to try to figure out who is responsible for the main event or disaster, and it is never easy. Most sagas describe what modern air-crash investigators would call an “error chain,” with several opportunities to break the chain, none of them taken. In the Laxdæla Saga, “The Saga of the People of Laxardal,” the central event is the killing of Kjartan by his cousin Bolli. What causes it? Certainly, the fact that Bolli told lies to Gudrun Osvifsdottir and persuaded her to marry him when her preferred lover Kjartan was out of the country. Gudrun may then have sent Bolli off to kill his cousin out of mere anger and jealousy—though it certainly crosses Bolli’s mind that she might have expected Kjartan to win the fight, which would have left Gudrun, not for the first time, a widow and free to make new arrangements, possibly involving Kjartan. But then why was Bolli so anxious to cut out his cousin, with whom he was on very good terms, by stealing his intended?

The trouble there started two generations back, when their grandfather Hoskuld bought an expensive Irish slave girl from a Russian. The really galling things about this were, first, that she turned out to be a princess, the daughter—though this looks very like the usual Icelandic brag about noble origins—of someone plausibly identified as King Muirchertach na gCochall gCroicenn, Muirchertach “of the Leather Coats” (d. 941); and second, that her illegitimate but unexpectedly well-born son Olaf the Peacock, father of Kjartan, turns out to be smarter, richer and more favored than his legitimate half-brother Thorleik, father of Bolli. He is furthermore held to have inherited much more than he should have done, including the intangible but vital family “luck.” So there is a grudge there from way back, a feeling on the part of everyone in Bolli’s family of having been demoted unjustly to number two.

However, an even more immediate reason involves the Myramenn and their avarice. In the Laxdalers’ Saga, Olaf the Peacock, the concubine’s son, marries Egil’s daughter Thorgerd: in view of her family pride a very good way of showing he has arrived. A Norwegian called Geirmund then asks for their daughter Thurid, and Olaf, who can see the future, turns him down. Geirmund then bribes Thorgerd to talk her husband round, which she does. The marriage is a disaster. Geirmund, predictably, runs out on Thurid, and Thurid decides to arrange her own childcare and alimony settlement by dumping their baby on Geirmund and stealing his precious sword with the razor edge and the walrus-ivory handle, “Legbiter.” Geirmund tries to buy it back, but Thurid refuses out of spite, and Geirmund puts a curse on it.

This is the sword that Bolli uses to kill Thurid’s brother Kjartan. While the killing is therefore partly Bolli’s fault and partly Gudrun’s, and Hoskuld’s fault from way back, as well as Thurid’s for giving the precious sword to the wrong man, one contributor to the whole chain is certainly Thorgerd, with her ignoble and short-sighted sacrifice of family prospects for money. That’s just like her father and grandfather, some would say, and so is the savage way in which she drives her remaining sons on for vengeance for their brother.

And then there is the ugliness. The saga explanation is clear. Like the greed for money, it’s in the family. Egil’s great-great-grandfather is Ulf the Fearless, of whom nothing else is known. His son Bjalfi, however—about whom even less is known, since he does not have so much as a nickname—married a wife called Hallbera, and she is the sister of Hallbjorn Halftroll, the father of Ketil Hængr (Salmon or Trout?), himself the progenitor of another famous family, the Hrafnistumenn, the men of Hrafnista. There are four sagas and a þáttr about him and his descendants. All are in effect fairy tales, about fighting legendary monsters, giants, and trolls.

Hrafnista, however, is a real place, an island off the coast of northern Norway, in Hålogaland; its modern name is Nærøy, from the earlier *Njar∂ar-ey, the “island of [the god] Njorth.” It has to be remembered that Norway is an extraordinarily long-drawn-out country, more than a thousand miles south to north, and Hrafnista is very close to the Arctic Circle and the limit of possible Norse habitation. Or should that be possible human habitation? In Ketil’s Saga, it is clear that while the Hrafnistumen are the furthest people to the north, there are other creatures beyond them; and it’s also fairly clear, though never at any point admitted, that Ketil’s father, Hallbjorn Half-troll, has some kind of arrangement with them. When Ketil, like all saga heroes, starts showing signs of restlessness, his father tells him very carefully which fjords he can go into and which he cannot.

Ketil, of course, again like all saga heroes, takes no notice and goes into one of the forbidden fjords. There he finds smokehouses and blubber pits, and in them not just walrus meat and polar bear meat but human meat too. He lies in wait for the mighty, intelligent, man-eating hunter, who is of course a troll, and kills him. After this, Ketil too starts making his own arrangements with the trolls, including marrying one of them and reinforcing the troll bloodline, which he himself has from his father.

What all this means is not clear. Some suggest that by “trolls” the Norse meant to indicate the Sami hunters who do indeed live to the north of Hålogaland. But the Sami are quite familiar in sagas and in nonfictional works—an important part of Norwegian kings’ income came from the Sami tribute of furs and hides and other high-value items like walrus ivory, and no one calls them trolls. Nor does Sami ancestry square with the reputation for unusual size and strength of part-troll families like Egil’s.

Maybe the whole idea is a projection of the natural fears of people living in the unusually hostile landscape and climate of sub-Arctic Norway, something well understood also by their Icelandic descendants. But in any case we can see that the author of Egil’s Saga meant to indicate that the troll blood inherited from what must have been Hallbera’s troll mother runs true, but not consistently, in the Myramen. Egil’s grandfather is called Ulf, like his great-great-grandfather, but where the latter’s nickname was “The Fearless,” the former is called Kveld-Ulf, “Evening Wolf.” What this means is that it is not a good idea to visit him when it’s getting dark. He is thought to be a shape-shifter, a were-thing of some kind—visitors don’t hang around to investigate further.

The next two generations both show the same pattern. In each there are two brothers, and while one is the typical saga hero, handsome, gifted, cheerful, generous, and so on—what in the wrestling world used to be called a “blue-eyes”—the other is dark, ugly, bald, and (overwhelmingly) mean. Both the “nice guy” brothers, that is to say, Egil’s brother and his father’s brother, are called Thorolf. Egil himself takes after his father, Skallagrim, in looks and temperament. Some of the Hrafnistumen emigrated to Iceland as well, and Egil carries the sword Dragvandil, which came to him from Grim Hairy-cheek, son of Ketil Hæng (himself presumably a quarter troll) and his full-blood troll wife Hrafnhild. Egil is the way he is because he’s part-troll.

Reprinted with permission from Laughing Shall I Die: Lives and Deaths of the Great Vikings by Tom Shippey, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2018 by Tom Shippey. All rights reserved.