Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

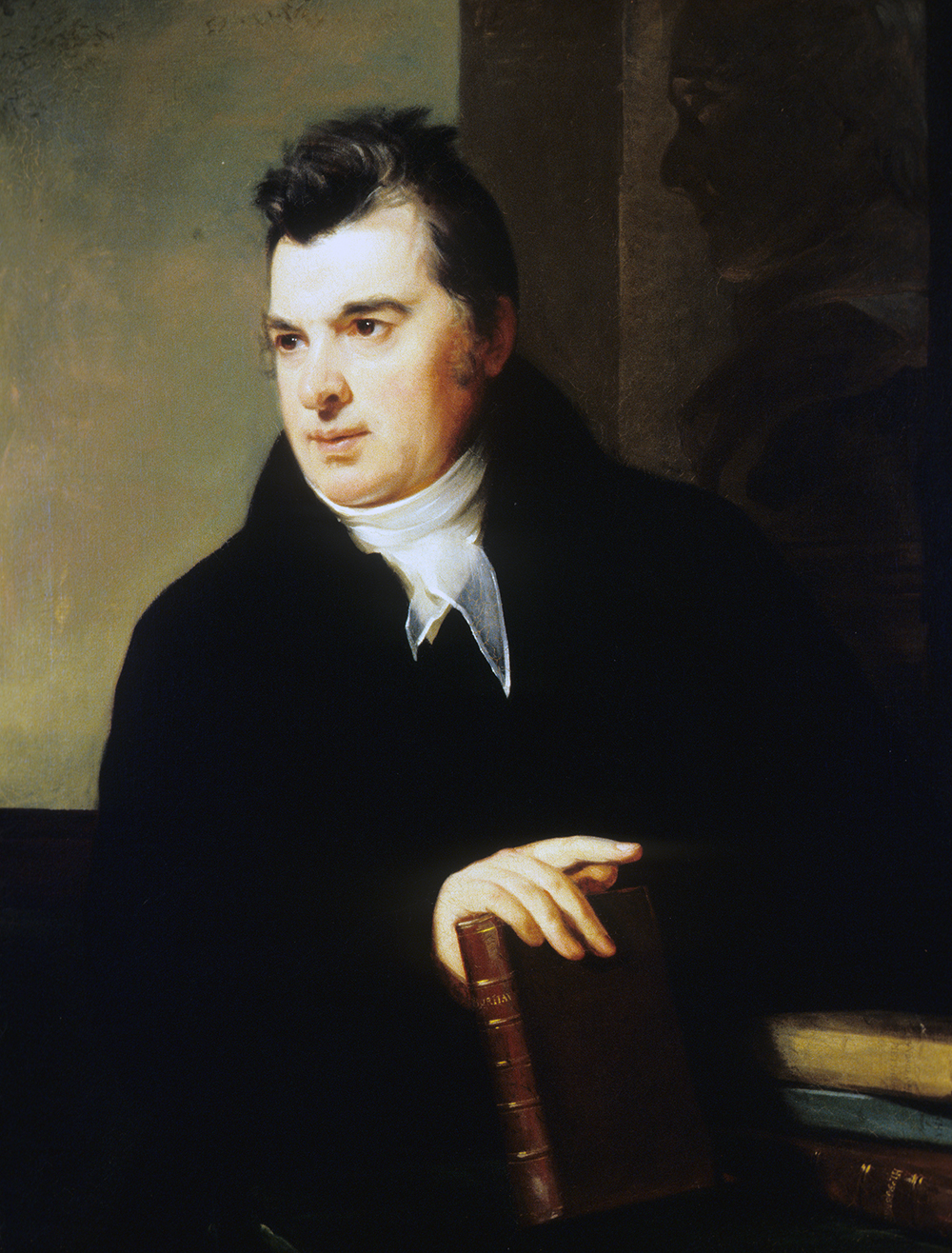

This week’s selection comes from Victoria Johnson, author of American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic, now out from Liveright.

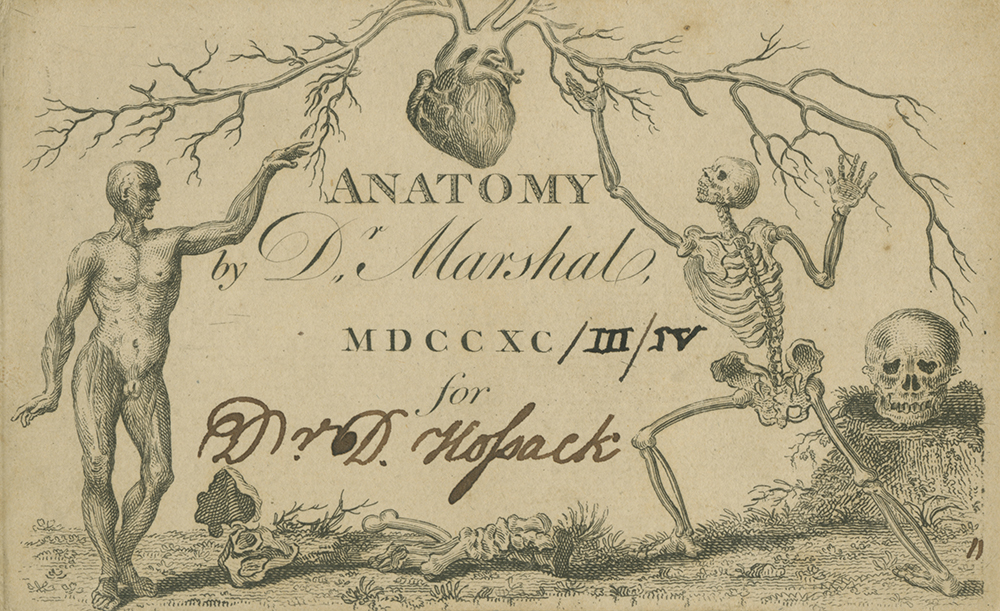

The above ticket gained young American doctor David Hosack entrance to the lectures of Dr. Andrew Marshal, one of late eighteenth-century London’s foremost anatomists.

Hosack had grown up in occupied Manhattan during the Revolutionary War. Soldiers bore their wounded down the streets to the impromptu field hospital inside King’s College. Out in the harbor, disease-ridden British ships held dying American prisoners. When New York became the first capital of the United States in 1785, the teenage Hosack found himself crossing paths with the men who had won the war and brought the new nation into being. For Hosack and his peers—the first post-Revolutionary generation—the challenge was to invent a new sort of heroism. Hosack decided to devote himself to saving American lives.

A century before the discovery of X-rays, autopsies were the only way doctors could see what lay beneath the human skin. (Autopsy means “seeing for oneself.”) In 1788, as a student at Columbia College—the new name for King’s College—Hosack risked his own life to help protect the college’s anatomical specimens from a mob enraged by the practice of corpse dissection. He was bashed on the head with a rock and narrowly escaped becoming one of the riot’s fatalities.

Hosack decided to pursue advanced studies in London, a city where dissection was less controversial. When he sailed back to New York in 1794, he brought home a sophisticated knowledge of the human body and new surgical procedures that he would be the first to perform on U.S. soil. He also discovered botany in Great Britain, returning as the best-trained American medical botanist. In 1797 Hosack saved the life of Alexander Hamilton’s fifteen-year-old son Philip with a medicinal plant, Cinchona officinalis. Soon after, he founded the nation’s first public botanical garden on twenty acres of Manhattan farmland—now the site of Rockefeller Center.

Hosack’s medical prowess earned him the trust not only of Alexander Hamilton but also of Aaron Burr, and in 1804 they both chose him to serve as the attending physician at their duel. Burr’s bullet lodged in Hamilton’s spine, and Hamilton died the next day. Hosack was asked to conduct an autopsy on the man he admired more than any other. Under his fingers, Hosack could feel the little spikes of shattered bone in Hamilton’s spine.

Hosack would conduct many autopsies during his long career, writing case notes to share with other doctors in an effort to help save American lives. When he lost one of his own sons to a mysterious ailment at the age of six months, he conducted the autopsy. He found the baby’s spleen terribly malformed, and in a letter to a fellow doctor, he wrote that had the baby survived, he “would have been a constant sufferer.” Seeing for himself—no matter how painful—was the only choice for Hosack.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Emily Ogden, author of Credulity: A Cultural History of U.S. Mesmerism

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Alastair Bonnett, author of Beyond the Map: Unruly Enclaves, Ghostly Places, Emerging Lands and Our Search for New Utopias

• Philip Dray, author of The Fair Chase: The Epic Story of Hunting in America

• Elaine Weiss, author of The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote

• Daegan Miller, author of This Radical Land: A Natural History of American Dissent

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing