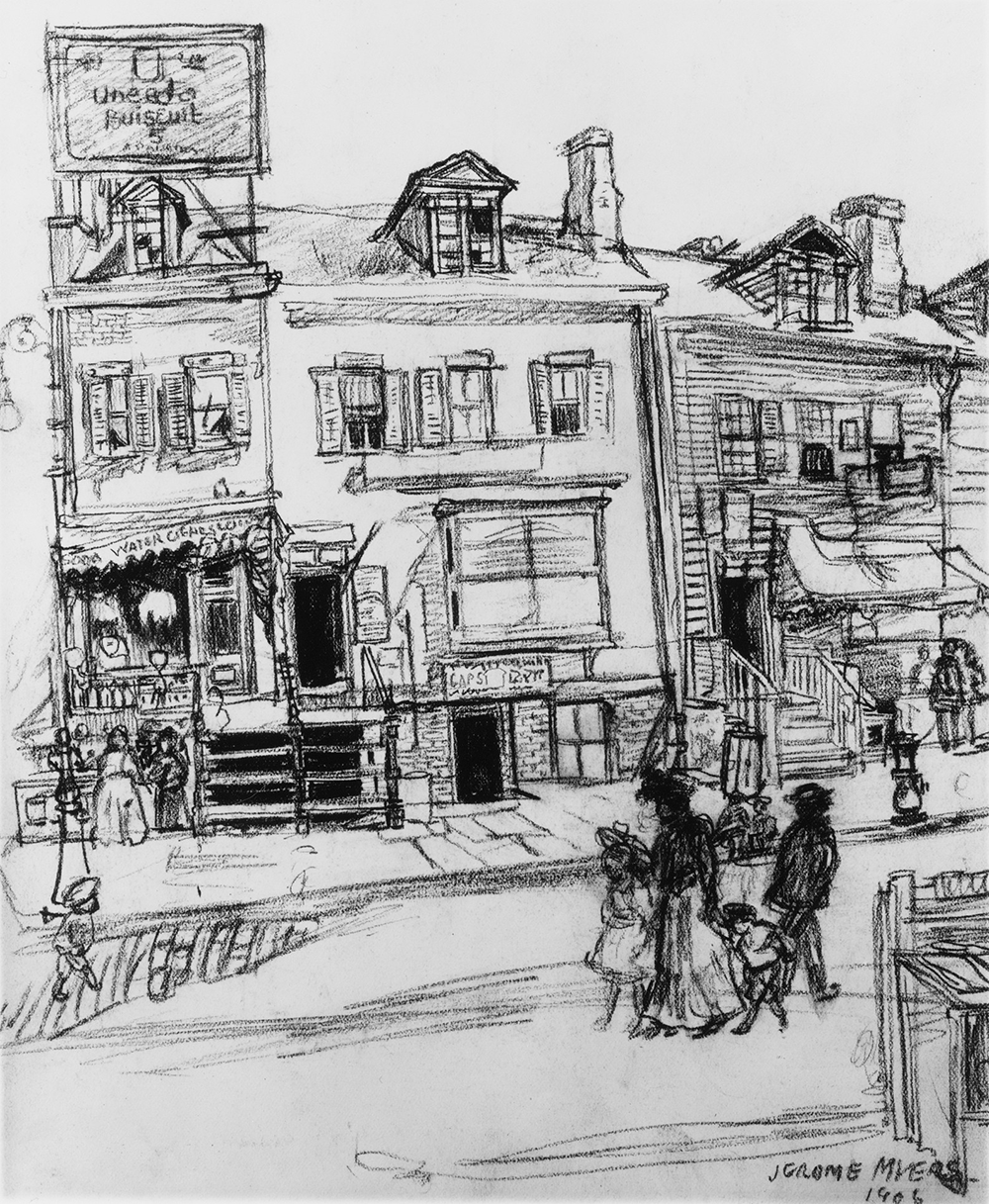

Street Scene (Hester Street), by George Benjamin Luks, 1905. Brooklyn Museum.

My ninety-seven-year-old father Julius recently amazed me by describing how, when he was hungry during the Great Depression, he would get an occasional free slice of salami from Izzy Pinkowitz, the “official” mayor of East Broadway, who happened to own the Hebrew National sausage factory on his Lower East Side block. How official? “Back then it was official,” he answered, after finishing his favorite old-fashioned cookie, the chocolate-covered Mallomar. “Look into it if you are so curious. The old street mayors of New York would make a good story.”

Father knows best. It is a good story.

New Yorkers are used to hearing some local power players called the “mayor” of their streets, but not all know the time and place where the idea was invented: during the Civil War, in the immigrant-heavy Lower East Side.

Although the Oxford English Dictionary cites some neighborhood “mayors” in England from the nineteenth century, the first credited use I’ve tracked down on the American continent was by an Irish American journalist named Charlie Lynch, writing on spec for the anti-elitist New York Sun. Lynch cleverly built up the eccentrics on his downtown beat to gain inches and dollars, and when, in 1864, he dubbed young saloonkeeper Pat Connolly “the Mayor of Poverty Hollow,” the nickname delighted the public as well as Connolly.

During the Civil War the streets bounded by Pitt, Grand, Cannon, and Rivington did form a hollow on the Lower East Side. At the foot of a hilly block of Grand Street was a site crowded with poor Irish workers from County Tyrone who had relocated there after the Great Famine. The gabby Connolly, whose pub was on the ground floor of his shanty at 245 Delancey Street, had cultivated connections with his regulars and local politicians. It was likely Lynch who later christened downtown marriage broker Max Hahn the mayor of Avenue C and bestowed mayor of Second Avenue on Simon Steingut, a wealthy Tammany Hall captain who had built up a real estate and insurance business from tenement roots and gave Christmas blankets to the poor.

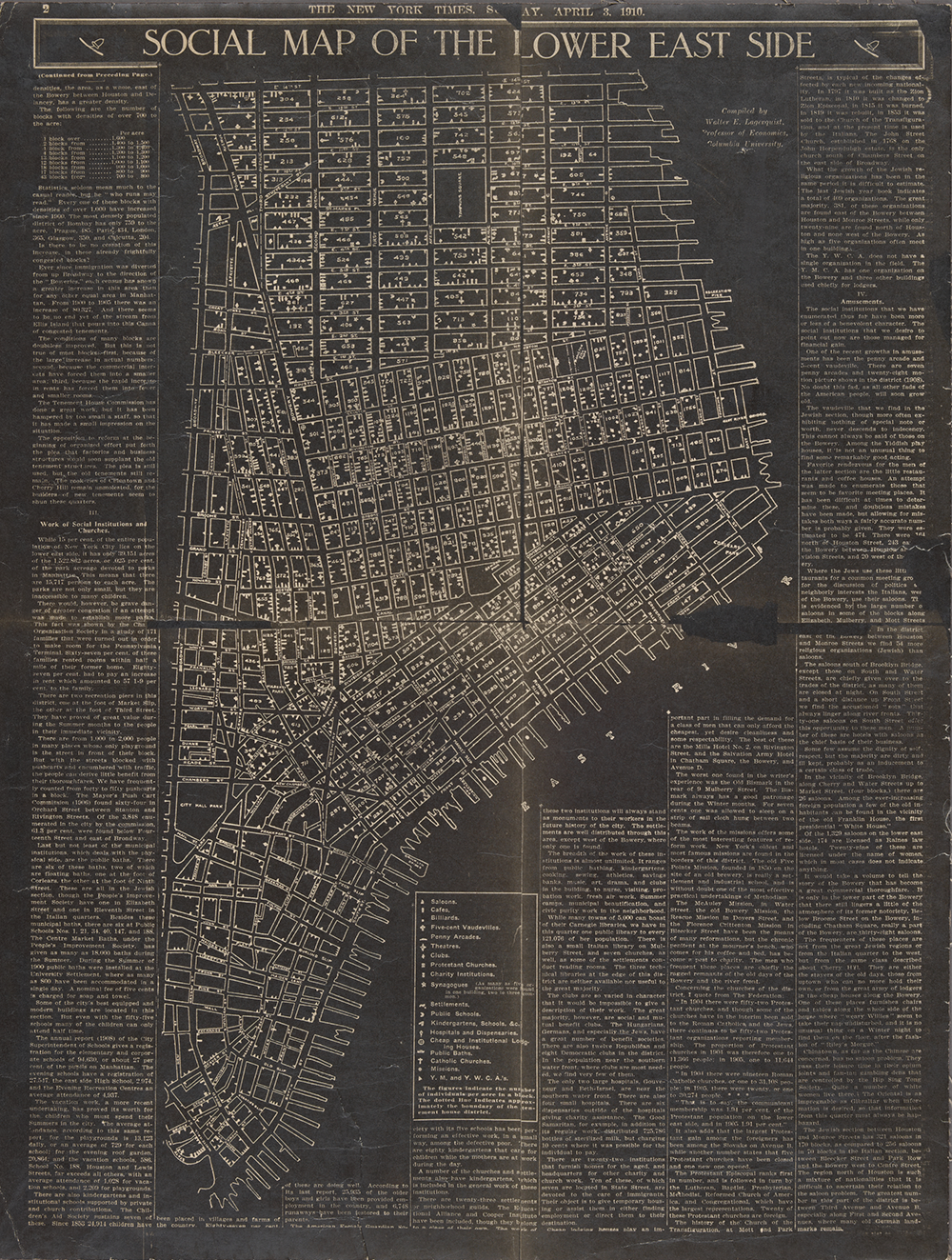

The immigration density of the old Lower East Side allowed neighborhoods to feel like different cities, if not distinctive worlds. The spread of newspapers in local dialects or languages also fueled the popularity of “street mayors,” as well as the business benefits that these civic ciphers got from their honorary titles. Some of the local mayors lived conspicuously beyond their means; since they could deliver local votes by granting favors, they were often suspected of being paid off the books by those in power at Tammany Hall.

These mimeographed mayors might be easy to dismiss as Pickwickian characters, but the titles actually did increase respect for these already locally influential men. Street mayors were likable fixers who cut through red tape and might settle between fifteen and twenty neighborhood disputes a day. They served social and even political functions, reflecting in part the graft and inefficiency of elected politicians.

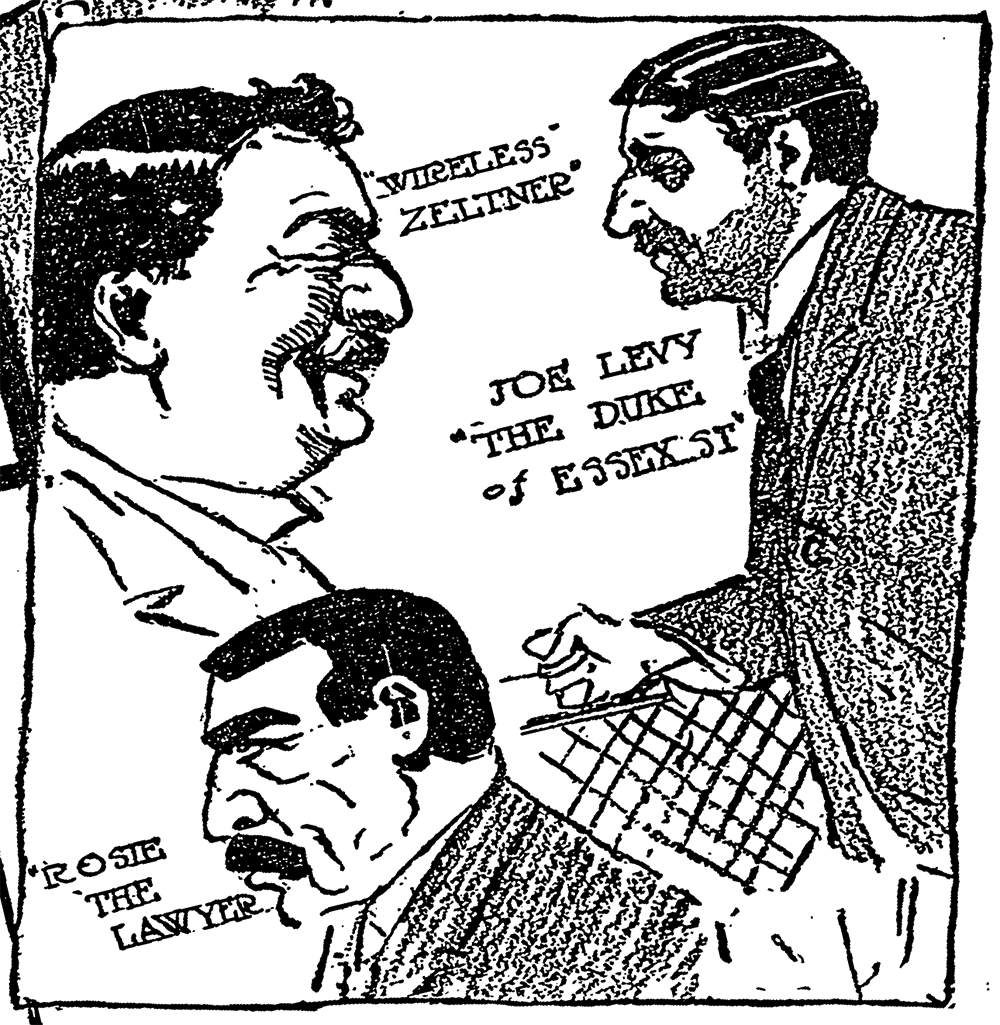

The history of street mayors takes a turn three decades after Charlie Lynch made Connolly a mayor. In 1895 a Jewish writer on the Lower East Side had a brainstorm that changed his life. Twenty-year-old Louis “Wireless Louie” Zeltner remembered reading Lynch’s character-driven articles in the Sun. (Zeltner’s Sun editor gave him the nickname “Wireless Louie” for his speed in filing a story about Essex Street Court lawyers chasing the Ludlow Street prison warden Charlie Anderson’s escaped pet parrot for the reward. “How did you get this so fast?” his editor marveled. The answer: “By wireless!”)

After a stint as a copy boy for the Sun, Zeltner pursued a more lucrative freelance career, placing amusing local stories in the New York Herald, the New York Tribune, and the Daily News, as well as in the Yiddish papers. Bilingual in Yiddish and English, he became the most trusted tipster for a now predominantly Jewish neighborhood. Its ethnicity had shifted when almost two million Jews passed through Ellis Island between 1880 and 1924. Three quarters of them settled in New York City, and most found a first home on the Lower East Side—including all four of my grandparents.

The Associated Press was formed in 1846 thanks to the rise of the telegraph, and by the Civil War news might be syndicated nationally. After the mass of Jews arrived, newspaper readers across the United States soon expected humor in stories coming from looked-down-upon immigrants trying to better themselves on the Lower East Side.

Zeltner took it upon himself to become Lynch’s heir apparent (and make more money) by focusing on a fresh crop of local players. With national syndication, Zeltner’s stories had greater impact than Lynch’s. Zeltner worked two ways, either charging other writers for access to a story or by writing it himself and then placing it. Even if he didn’t expect the national coverage he got for his new batch of street mayors—including John Leppig, mayor of Avenue A, and Louis Cohen, mayor of Seventh Street—he wouldn’t have been surprised that the local mayor concept worked on his Lower East Side streets. The immigrant community had no society columns, and just as a gentleman on Fifth Avenue might want to read who was making the biggest donations, those living below Fourteenth Street were fascinated by men with financial power living among their families.

“New York is the greatest city in the world,” Wireless Louie explained to another reporter amused by his ability to place stories when others were left frustrated. “But in reality, it is a lot of small towns knit together—only we must call them neighborhoods. We must keep the neighborhood spirit.”

When choosing block mayors, Zeltner looked for the men with the best backstories to capitalize on; all appreciated the significant free press and proof of their influence. The more colorful the man anointed, the better. Colorful sold papers. Colorful brought even more useful friends.

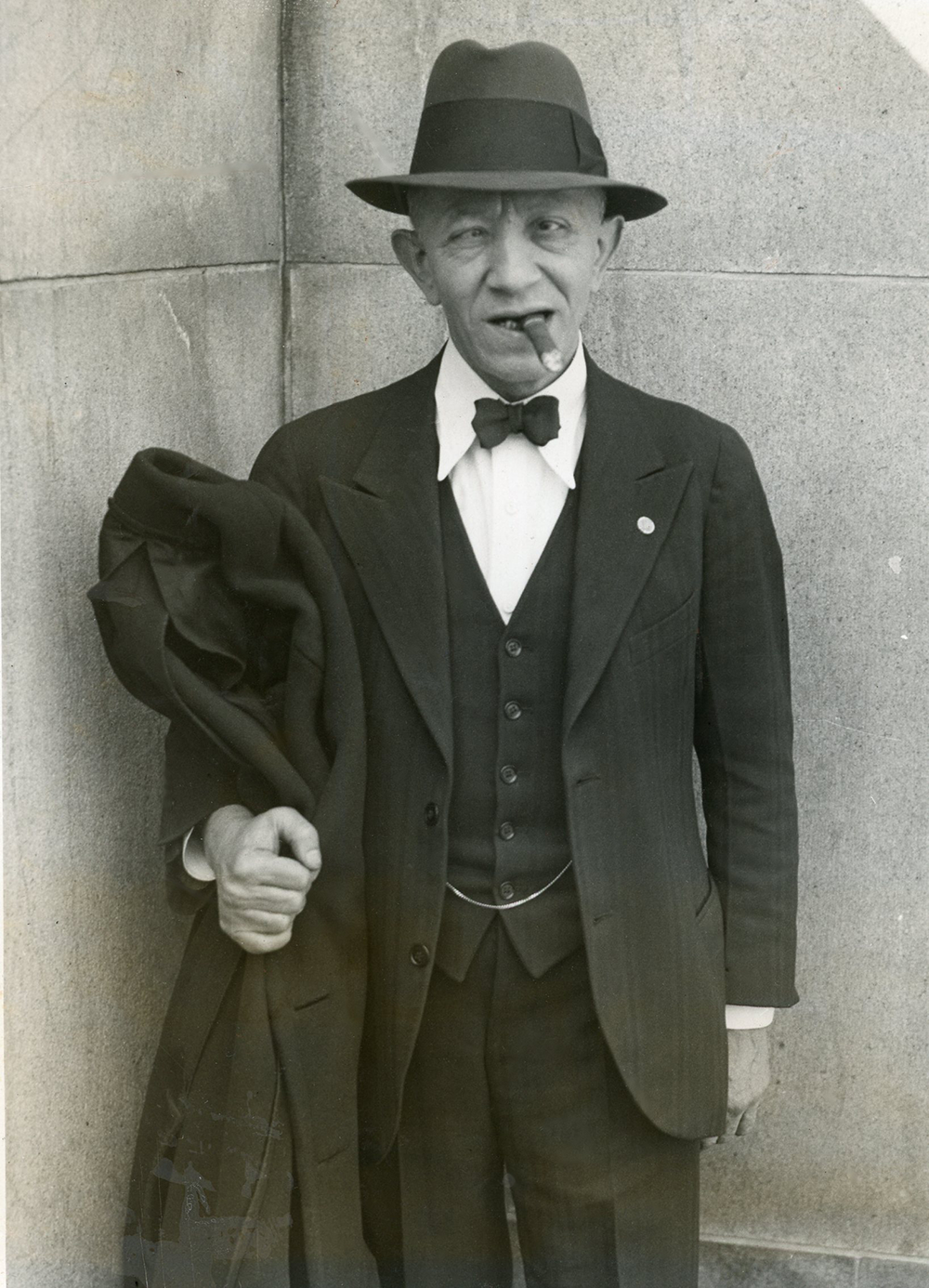

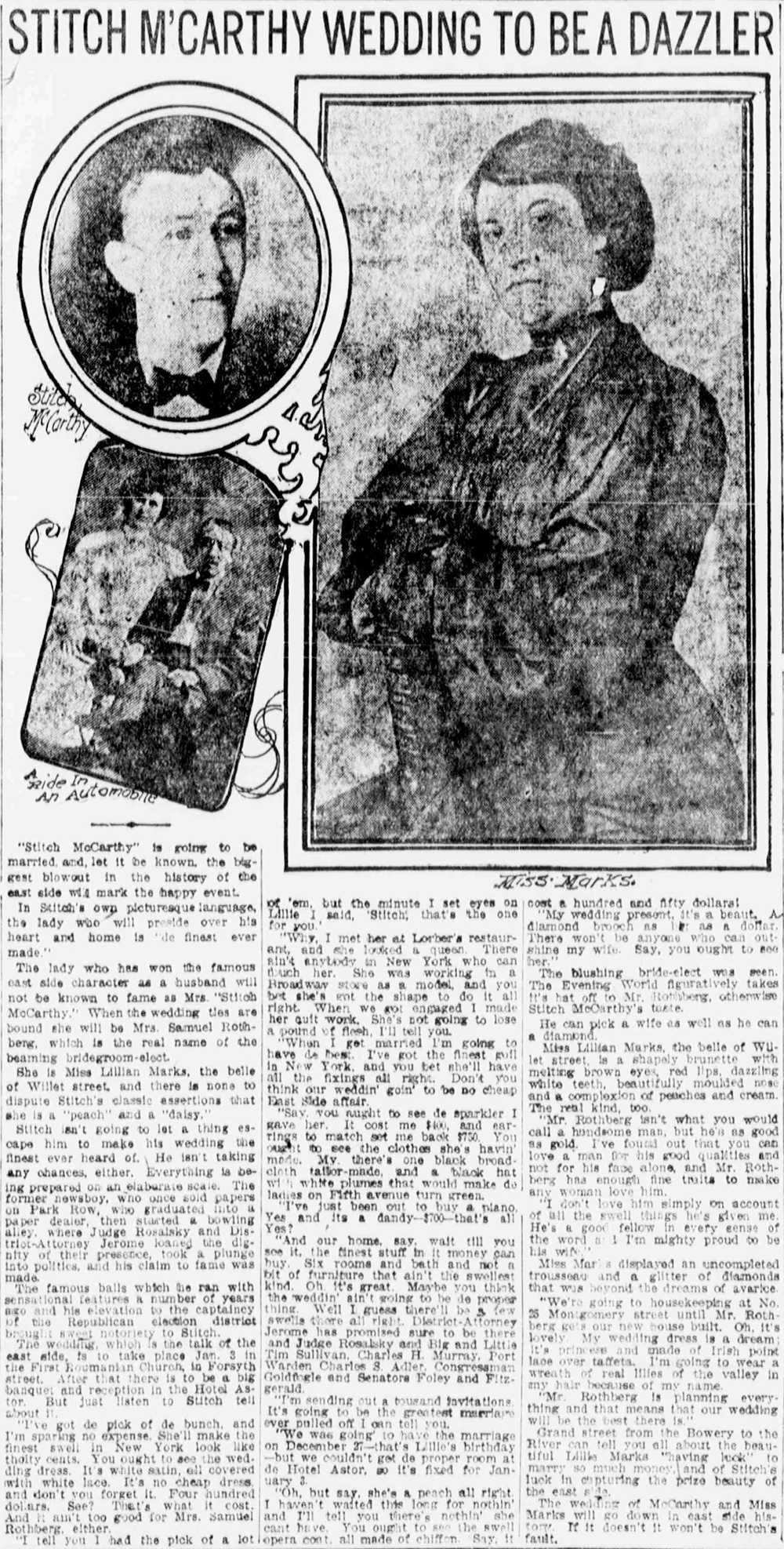

Perhaps the most flamboyant of the new bunch of street mayors was Stitch McCarthy, the mayor of Grand Street. McCarthy was a five-foot-tall cross-eyed Romanian Jew born Samuel Rothberg, always seen with a cigar in his mouth. He had arrived in New York at age five and was working by age six, growing up in the unsavory Mulberry Bend where Gangs of New York was set. By his teen years, Rothberg was tough as nails. He ran a newsstand at Broad and Wall streets in lower Manhattan, using his fists to claim his choice location.

At night he managed a small-time boxer who once was scheduled to fight a bantamweight named Stitch McCartney in Jersey City. As he later told the story (no doubt over and over), his client fled in fear at the sight of McCartney and the crowd booed. He went in the ring himself, flattened McCartney, and took a version of his opponent’s name for his own. McCarthy then used his money from the news business and boxing gigs to open a poolroom and bowling alley on Grand Street. That enterprise did so well he opened a bigger place at Forsyth Street called Stitch McCarthy’s Apollo Saloon. Next door he opened Eagle Bowling Alley, where his loyal customers included gangsters such as Harry Horowitz aka Gyp the Blood, “Dago Frank” Cirofici, and Whitey Lewis.

Prohibition closed McCarthy’s Saloon in 1919, and then McCarthy lost $25,000 investing in a new kind of bowling ball. But he eventually found financial salvation in the Volstead Act that had doomed his saloon. Men who violated the rules for a drink here and there rarely skipped town; they were a sound investment. He opened an office at 91 Centre across from the courts and handled bail bonds for many people, including, by his later account, such Jewish mobsters as Legs Diamond, Dutch Schultz, and Arnold Rothstein. His success as a bail bondsman soon put him in a chauffeured Hispano-Suiza town car that elicited gasps. Forget a Rolls-Royce—this was as glamorous a ride as you could get in the 1920s.

By 1907 over 76,000 votes came from the Lower East Side’s eleven subdistricts. These astounding numbers attracted attention at Tammany Hall—where under-the-table cash gifts to bolster support from the street mayors were of course never mentioned by Zeltner or reporters. Perhaps Zeltner got cash from shady sources, too. Over time the street mayors organized into formal “benevolent” groups, and their dinners and outings made great copy.

To gain the trust of local residents who despised elected authorities, street mayors did everything from giving urchins coins for needy mothers to stopping dogs from barking at three a.m. They funded excursions for the poor, helped with the rent, and paid coal bills. Sometimes the mayors were wealthy, but whether the money came from Tammany Hall or from their own pockets is hard to determine, though the former seems more likely. Those with saloons had a telephone used by their entire block. Those with floral shops made sure every funeral had a wreath. Mayors were called on as philanthropic boosters at the most boring of events; they were unpaid marriage brokers. Over time Zeltner and his “titled” mayors likely believed they were the epitome of noblesse oblige.

Maintaining the right to be called mayor of a street was no joke, and street mayors believed it required years of civic duty to deserve their designation. I haven’t come across a mayor who had his title stripped due to disgrace or inactivity. Being named a street mayor by Zeltner was considered a lifetime appointment unless a mayor moved far away. Stitch McCarthy was known to say that a true mayor would always see to it that a poor man on his block was properly buried. (Fortunately, several of Zeltner’s mayors, such as mortician Angelo Rizzo, mayor of Mulberry Street, owned burial grounds in local cemeteries.)

By the 1920s, after a brief stint as an alderman, Zeltner left reporting behind and settled on a full-time career as a press agent. He continued to place stories about the city’s street mayors, even organizing them into a group called the New York League of Locality Mayors that held banquets at the long-gone Hotel Astor, where they picked a chief mayor. An earlier version of a street-mayor community, the East Side Mayors Association run by Max Hahn at the turn of the century, was never as fancy or formal as Zeltner’s coalition.

One of Zeltner’s banquet regulars was Frank Dostal, the mayor of Avenue B, born on East Third Street near B in 1892. As a kid, Dostal bought roses that florists had discarded, cut off the stems, and sold them on the street; eventually he made enough money to open his own shop at 42 Avenue B. This florist (who was also a city alderman from 1914 to 1916) got mighty rich in the age of Tammany Hall; the money trail is impossible to confirm now. When Dostal moved to Hollywood in 1930, he relinquished his mayorship to Dr. Sam Wagner, an ophthalmologist. The ceremony marking the changing of the guard occurred at the Pump, a Lower East Side fire hydrant at Avenue B and Third Street. Here Dostal was given farewell gifts, including a ram’s horn walking stick and an umbrella inscribed in gold, and a gaggle of mostly Jewish mayors of other streets sang Irish folk songs like “Mother Machree” and “Where the River Shannon Flows.” The mayor of Delancey couldn’t come and telegrammed, “Stay away from Clara Bow!”

The mayor of Delancey Street was born Phillip Kardonick in 1877. He owned a popular Jewish Bavarian cabaret called Phillip’s Russian Bavarian at 48 Delancey Street, where an orchestra in Russian blouses played old-country Yiddish tunes. Since his customers often called him Mr. Phillips because of the Phillip’s Russian Bavarian sign, he switched the order of his names and got in the papers as Mr. Kardonick Phillips. He had come to America in 1902, running away from anti-Jewish rioting in Kishinev, then the capital of Bessarabia Governate in the Russian Empire, around Easter. During the riots many Jewish women were raped, forty-nine Jews were killed, and 1,500 Jewish homes were damaged. After this early pogrom, a group of Jews living on the Lower East Side began to organize financial aid for Jews in Russia, publicizing their persecution. Phillips took up the cause, speaking publicly about the growing crisis and raising money for loved ones back home trying to escape. While Phillips may have accepted undeclared currency, as all the mayors did, several of his restaurants on Delancey Street prominently displayed signs reading let no hungry man pass twice through this door. He made good on it, feeding the impoverished for free. A 1929 article notes that he offered two thousand homeless men from the Bowery a nine-course meal in his restaurant.

Max Dick, mayor of Allen Street, seems to have been the most truly benevolent of the many street mayors. Born in the part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that became Poland, Dick was evicted from 69-73 Rivington Street in November 1891; standing on the street, he vowed to own the building one day. Dick kept his word and became a real estate owner who continued to charge only $5 a room per month even after property values rose in the Jazz Age. He turned his former home into what Zeltner called the “House of Babies”: reporters were told the benevolent landlord gave a $50 cash bonus for every child born to his tenants, and if a ninth child was born at the address, the parent was presented with $150. No one was ever evicted.

During a dinner meeting in September 1929, just before the stock market crash, Jack Spero was elected chief mayor of the New York League of Locality Mayors. The meeting became briefly chaotic when someone stole the hat belonging to Abe Fagin, the “Mayor of Hunt’s Point,” a crowd-pleasing detail Zeltner fed to the press.

The street mayors were about to face far greater complications than a missing hat. They were needed more than ever during the Great Depression, as saviors of last resort. They came through as best as they could. Izzy Pinkowitz, the mayor of East Broadway who sent me down this rabbit hole, owned the biggest kosher factory in the neighborhood, the Hebrew National Kosher sausage factory at 155 East Broadway. He ran a salami and bologna breadline during the Depression and had five hundred nonpaying customers a day, including my father.

On April 18, 1932, all the street mayors marched together behind the real mayor of New York, Jimmy Walker, in a ceremony marking the widening of Allen Street after the First Avenue elevated tracks came down. It’s hard not to wonder what the playboy Walker made of his little mayors, but I’ve found no record of any New York City mayor commenting on a street mayor. Did the elected leaders prefer to ignore their populist competition?

The first little mayor of Brooklyn was added to the New York League in June 1932, when Louis Zeltner named Morris Morrison the mayor of Borough Park on the steps of the Borough Park Talmud Torah. Chomping his cigar, Stitch McCarthy spoke for the ten mayors present for the occasion: “There would have been more of us, but some of us are undertakers and had to work this morning. Four of them are playing pinochle over at Essex and couldn’t leave the game.” Then Zeltner, the man one paper jokingly called “Lord Mayor,” presented a golden locality mayor badge to Morrison and proclaimed it a great day for Brooklyn.

This decade saw even more mayors outside of the Lower East Side added to the League. Poy T. Yee, the first Chinese mayor of the group, was elected mayor of Chinatown on February 4, 1934, over a fifteen-course dinner at the Port Arthur Restaurant on 7 Mott. The mayors wore novelty hats with pigtails. (Cringeworthy, yes.)

Tap dancer Bill Robinson, better known as Bojangles, became the first black mayor of Zeltner’s league. Robinson’s first “official” act as mayor of Harlem was to bid adieu to Cab Calloway and his band, who were heading to London on the SS Majestic in February 1934.

In 1935 the locality mayors voted to make the real mayor of Dublin, Alfred “Little Alfie” Byrne, an honorary member. McCarthy, who was Jewish, declared (with a terrible attempt at a brogue), “We Irishers have to stick together.” Izzy Pinkowitz said he would make sure Byrne had his best kosher bologna before departing for Dublin on the SS Olympic.

When the mayor of Grand Street died days after suffering a heart attack in 1937, he was perhaps the only McCarthy ever laid in his casket with a white yarmulke and prayer shawl. Thirty cars, which carried fourteen street mayors, drove out to a cemetery in Queens. According to the papers, McCarthy got his long-stated wish: “Here Lies a Good Guy” was engraved on his headstone.

In the wartime years there were arguments about how the organization could continue to play a significant role. Usually when mayors weren’t talking to one another, it was just an amusing riff Zeltner staged for publicity and public entertainment. But after disagreements between the mayors and Zeltner grew into an actual feud in 1946, Saul Graff, the mayor of Crown Heights, took over the New York League of Locality Mayors, and Zeltner left to form the Old Time Locality Mayors Inc. It seems the street mayors were building up a bureaucracy of agencies to rival an actual government. Street mayors also ceased to be solely local characters, with Hollywood entertainer Danny Kaye cast as mayor of Brooklyn. The social and political forces that had made those mayors important figures had begun to die out. Already established celebrities were a better bet for making the news.

After Zeltner died in 1952, the Old Time Mayors group was at a loss. In 1957 Bronx businessman Dominick Della Rocca reorganized the group as the Community Mayors, an organization that nobly focuses on kids with special needs and remains around today. Still, it boasts much less vibrant characters and little public recognition—has anyone even heard of one of their mayors?

I talked to Louis Zeltner’s sixty-five-year-old grandson David Zeltner in his New York law office near midtown. Though he never met his grandfather, David Zeltner did know that Louis (who had eleven children) had made significant money during Prohibition years but would rather not find out how, “lest we are in Michael Cohen territory.” David Zeltner grew up with Paul Bunyanesque stories of his grandfather and marveled at how much I’d found that corroborated them. “I always thought the limos and the dinners were legend, but I guess what I always heard about him turned out to be true. Fact is stranger than fiction! And we all know politics remain the same.”

While the idea of a local mayor turned into more of an exercise in branding after World War II, the idea of knowing your local New York City fixer stuck around—and still does today. Those who live in my neighborhood of Corlears Hook, once nicknamed Poverty Hollow, would agree that politics relies on who and what you know. Until recently, the most powerful man who lived on my street was Sheldon Silver, the longtime speaker of the New York State Assembly. My Corlears Hook voting bloc knew he might be rotten to others but he was loyal to his constituents, so they kept electing him.

In 2015 Silver was tried and convicted of corruption, including receiving nearly $4 million in unlawful payments for helping secure government funds for a prominent cancer researcher, Dr. Robert N. Taub of Columbia University, and two New York real estate development firms, Glenwood Management and the Witkoff Group. Yet he still has his supporters. While he was stealing money from other New Yorkers, Silver was also securing funds for Lower East Side schools and hospitals and helping the elderly fight eviction. More than once, he wound up as savior of last resort, like the Lower East Side street mayors before him. A local might whisper in your ear, “Go ask Shelly’s office, and tell them you grew up on Grand Street.”

First sentenced to twelve years in prison, Silver had his conviction tossed out after the Supreme Court redefined political corruption. In a 2018 retrial, he was again found guilty and sentenced to seven years in prison. It is not yet clear who will be the new unofficial mayor of Grand Street. There is a turf war going on between possible successors, including the leaders of the progressive Grand Street Democrats and the Harry S. Truman Democratic Club; the latter had reliably delivered votes for Silver. Residents of the far east Lower East Side are familiar with rambling photocopied letters from riled-up neighbors slipped under doors and name-calling in private hyperlocal Facebook groups—including one for my apartment complex. (It’s Silver’s home, too—at least until October 5, 2018, when he is scheduled to begin his prison term.) Posts about local politics can get as heated as a discussion in the Lower East Side’s Garden Cafeteria during the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917.

A powerful elected official may not be an exact match to the jolly old street mayors, but there’s no denying Silver filled the “I’ll fix it for you” role. Nobody ever called Shelly Silver jolly, though, and it’s too bad he never took a likability lesson from Stitch McCarthy or Izzy Pinkowitz. Until his power was stripped by criminal conviction, he was famously not a man it was wise to cross.

You probably wouldn’t want to cross the old locality mayors either. I searched for a juicy anecdote about a street mayor getting back at an enemy, but perhaps it is not surprising Zeltner never let that kind of story into print.