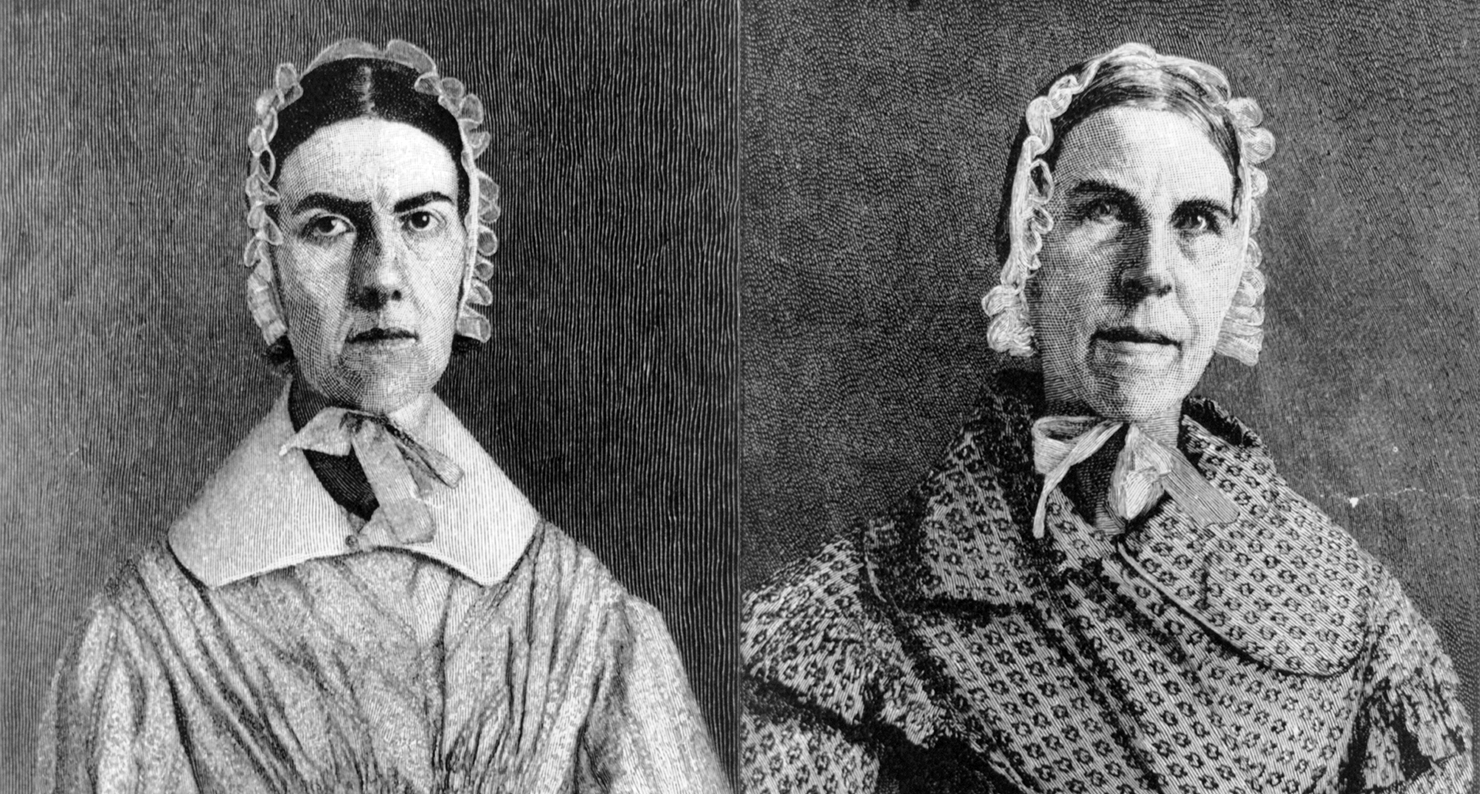

Angelina Emily Grimké (1805–1879) and Sarah Moore Grimké (1792–1873). Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Louise W. Knight, who is writing a book about Angelina and Sarah Grimké. The sisters traveled the country in the early nineteenth century giving talks on women’s suffrage and the abolitionist movement. Angelina Grimké would have celebrated her 213th birthday on February 20.

In the summer of 1837, Angelina and Sarah Grimké were traveling in eastern Massachusetts. The white, South Carolina–born sisters were working on behalf of the American Anti-Slavery Society, lecturing and organizing to end slavery immediately in the southern United States. During their travels in New England, they drew the ire of the conservative wing of the Massachusetts Congregational ministry, which opposed the immediate abolition movement. In July a pastoral letter was read from Congregational pulpits across the state condemning women who entered what was called the “public sphere” to give speeches supporting “reform.”

The attacks did not surprise the sisters. When they first began speaking in public about slavery six months earlier in New York City, many privately told them that they should stop. The sisters’ actions were indeed groundbreaking. While Frances Wright and Maria Stewart had given reform lectures earlier, neither had taken to the road on behalf of a single controversial reform. Catharine Beecher, prominent female educator, did not approve. Like the conservative Massachusetts Congregational clergy, she and her famous father, the Congregational minister Lyman Beecher, supported sending African Americans to Africa as a solution to slavery and opposed the immediate abolition movement.

In May 1837 Catharine published a pamphlet criticizing that movement as seriously misguided and Angelina Grimké, with whom she had been friends in the 1820s, for violating woman’s God-given place as subordinate to men. In response to Beecher’s pamphlet, Angelina published her own, in the form of a series of letters. The first letter was published in June in several reform newspapers. Two of the last three letters dealt with women’s equality and were as much a response to the pastoral-letter controversy as to Beecher’s limited vision for women. In the second-to-last letter, the first half of which is reprinted here, Angelina sets aside Beecher’s arguments and forthrightly states her own regarding women’s full human equality.

The investigation of the rights of the slave has led me to a better understanding of my own. I have found the Anti-Slavery cause to be the high school of morals in our land—the school in which human rights are more fully investigated, and better understood and taught, than in any other. Here a great fundamental principle is uplifted and illuminated, and from this central light, rays innumerable stream all around. Human beings have rights, because they are moral beings: the rights of all men grow out of their moral nature; and as all men have the same moral nature, they have essentially the same rights. These rights may be wrested from the slave, but they cannot be alienated: his title to himself is as perfect now, as is that of Lyman Beecher: it is stamped on his moral being, and is, like it, imperishable.

Now if rights are founded in the nature of our moral being, then the mere circumstance of sex does not give to man higher rights and responsibilities, than to woman. To suppose that it does, would be to deny the self-evident truth, that the “physical constitution is the mere instrument of the moral nature.” To suppose that it does, would be to break up utterly the relations, of the two natures, and to reverse their functions, exalting the animal nature into a monarch, and humbling the moral into a slave; making the former a proprietor, and the latter its property. When human beings are regarded as moral beings, sex, instead of being enthroned upon the summit, administering upon rights and responsibilities, sinks into insignificance and nothingness. My doctrine then is, that whatever it is morally right for man to do, it is morally right for woman to do. Our duties originate, not from difference of sex, but from the diversity of our relations in life, the various gifts and talents committed to our care, and the different eras in which we live.

This regulation of duty by the mere circumstance of sex, rather than by the fundamental principle of moral being, has led to all that multifarious train of evils flowing out of the anti-Christian doctrine of masculine and feminine virtues. By this doctrine, man has been converted into the warrior, and clothed with sternness, and those other kindred qualities, which in common estimation belong to his character as a man; whilst woman has been taught to lean upon an arm of flesh, to sit as a doll arrayed in “gold, and pearls, and costly array,” to be admired for her personal charms, and caressed and humored like a spoiled child, or converted into a mere drudge to suit the convenience of her lord and master. Thus have all the diversified relations of life been filled with “confusion and every evil work.” This principle has given to man a charter for the exercise of tyranny and selfishness, pride and arrogance, lust and brutal violence. It has robbed woman of essential rights, the right to think and speak and act on all great moral questions, just as men think and speak and act; the right to share their responsibilities, perils and toils; the right to fulfill the great end of her being, as a moral, intellectual, and immortal creature, and of glorifying God in her body and her spirit which are His.

Hitherto, instead of being a help meet to man, in the highest, noblest sense of the term, as a companion, a co-worker, an equal; she has been a mere appendage of his being, an instrument of his convenience and pleasure, the pretty toy with which he wiled away his leisure moments, or the pet animal whom he humored into playfulness and submission. Woman, instead of being regarded as the equal of man, has uniformly been looked down upon as his inferior, a mere gift to fill up the measure of his happiness. In “the poetry of romantic gallantry,” it is true, she has been called “the last best gift of God to man”; but I believe I speak forth the words of truth and soberness when I affirm, that woman never was given to man. She was created, like him, in the image of God, and crowned with glory and honor; created only a little lower than the angels—not, as is almost universally assumed, a little lower than man; on her brow, as well as on his, was placed, the “diadem of beauty,” and in her hand the scepter of universal dominion. (Gen: i. 27, 28) “The last best gift of God to man!” Where is the scripture warrant for this “rhetorical flourish, this splendid absurdity?” Let us examine the account of her creation. “And the rib which the Lord God had taken from man, made he a woman, and brought her unto the man.” Not as a gift—for Adam immediately recognized her as a part of himself—(“this is now bone of my bone, and flesh of my flesh”)—a companion and equal, not one hair’s breadth beneath him in the majesty and glory of her moral being; not placed under his authority as a subject, but by his side, on the same platform of human rights, under the government of God only.

This idea of woman’s being “the last best gift of God to man,” however pretty it may sound to the ears of those who love to discourse upon “the poetry of romantic gallantry, and the generous promptings of chivalry,” has nevertheless been the means of sinking her from an end into a mere means—of turning her into an appendage to man, instead of recognizing her as a part of man—of destroying her individuality, and rights, and responsibilities, and merging her moral being in that of man. Instead of Jehovah being her king, her lawgiver, and her judge, she has been taken out of the exalted scale of existence in which He placed her, and subjected to the despotic control of man.

I have often been amused at the vain efforts made to define the rights and responsibilities of immortal beings as men and women. No one has yet found out just where the line of separation between them should be drawn, and for this simple reason, that no one knows just how far below man woman is, whether she be a head shorter in her moral responsibilities, or head and shoulders, or the full length of his noble stature, below him, i.e. under his feet. Confusion, uncertainty, and great inconsistencies, must exist on this point, so long as woman is regarded in the least degree inferior to man; but place her where her Maker placed her, on the same high level of human rights with man, side by side with him, and difficulties vanish, the mountains of perplexity flow down at the presence of this grand equalizing principle. Measure her rights and duties by the unerring standard of moral being, not by the false weights and measures of a mere circumstance of her human existence, and then the truth will be self-evident, that whatever it is morally right for a man to do, it is morally right for a woman to do. I recognize no rights but human rights.

From “Letter XII: Human Rights Not Founded on Sex,” by Angelina Emily Grimké Weld, in Letters to Catherine E. Beecher, in Reply to an Essay on Slavery and Abolitionism, Addressed to A.E. Grimke (I. Knapp, 1838).