The Edison Kinetogram Catalogue, 1910. Wikimedia Commons.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

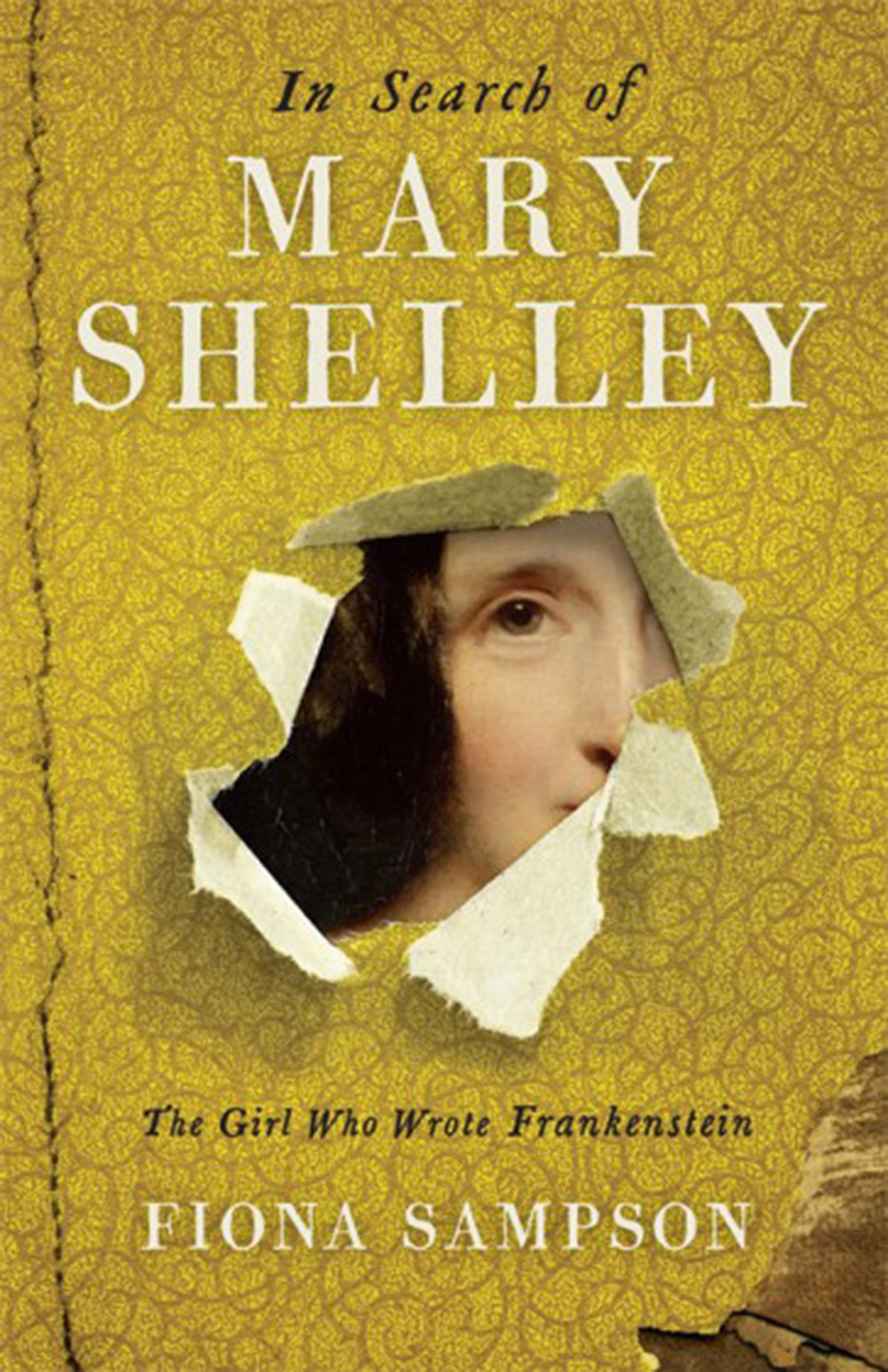

Our first selection comes from Fiona Sampson, author of In Search of Mary Shelley: The Girl Who Wrote Frankenstein, out this month in the UK from Profile Books and forthcoming in June in the U.S. from Pegasus Books.

Most of us know of James Whale’s 1931 film of Frankenstein, which created the simplified iconography we associate with the story today. It was Whale and his scriptwriters, not the author he styles “Mrs. Percy B. Shelley,” who came up with those clichés of kitsch sci-fi: the gleaming lab, the hunchback assistant, electrocution by lightning, Boris Karloff’s stiff-legged, bolt-necked monster.

But altogether closer to Mary Shelley’s intensely psychological, ultimately mysterious original is the silent movie that preceded Whale’s big picture by more than two decades. In 1910 Edison Manufacturing Company released a fourteen-minute melodrama directed by the thirty-three-year-old J. Searle Dawley. Dawley, who had worked his way up from the backroom of the movie industry, modestly described it as a “liberal adaptation” of the novel. In fact it’s a fascinating work of translation and abridgment that makes Frankenstein into a kind of Jekyll and Hyde, torn between good and bad. You almost expect a split screen, then the film goes and provides early versions of just this: the anteroom visible through French windows, the large mirror propped between floor and ceiling.

Does this represent good and evil, or the conscious and unconscious worlds? Chemistry flirts with alchemy as Frankenstein’s creature burns into being on Dawley’s reversed film stock, arms flapping with horrifying lack of meaning. Hatched, he’s even more ambiguous. Is this Frankenstein’s hubris, personified literally as well as symbolically? At the film’s uncanny end he surrenders to the mirror, disappearing into it. Was it all a dream? We can’t be sure. But the blurry, jerky film stock that makes us feel we’re watching through tears, or in a high wind, only adds to the effect. Not brilliant trompe l’oeil, but the smurred glimpse of something half-remembered, an old anxiety or superstition, lingers with us. As myths will.