Dorothy and Lillian Gish and D.W. Griffith at the White House, 1922. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Helen Klein Ross, author of The Latecomers, now available from Little, Brown & Company.

The year 1915 marked the fiftieth anniversary of the end of the Civil War. Monuments to Confederate and Union heroes were being dedicated all over the country. Woodrow Wilson, a fan of Jim Crow laws, was president. He had allowed federal workplaces to segregate again.

Enter Thomas Dixon Jr., Wilson’s classmate from Johns Hopkins. A film had just been made of Dixon’s second novel, “the true story” of the South under Reconstruction. Would the president, he wondered, be interested in viewing it? (He would.)

“History written with lightning,” Wilson declared of The Clansman, the second film ever to be screened in the White House. It was an endorsement guaranteed to head off resistance from town censor boards charged with shutting down entertainment deemed unsuitable or incendiary to the public.

The Clansman was a silent movie with title cards. It depicted whites as victims and blacks as villains. Benevolent former masters were denied votes and subjugated by newly freed blacks taking over the country. In an early scene, black legislators sit at desks, shoeless and drunk, too busy stuffing their faces with fried chicken to work. The title card read: “An historical facsimile of the State House of Representatives of South Carolina in 1870.” South Carolina had been the first state to elect a majority-black legislature and that the card implied that the apish behavior depicted was historically accurate, too.

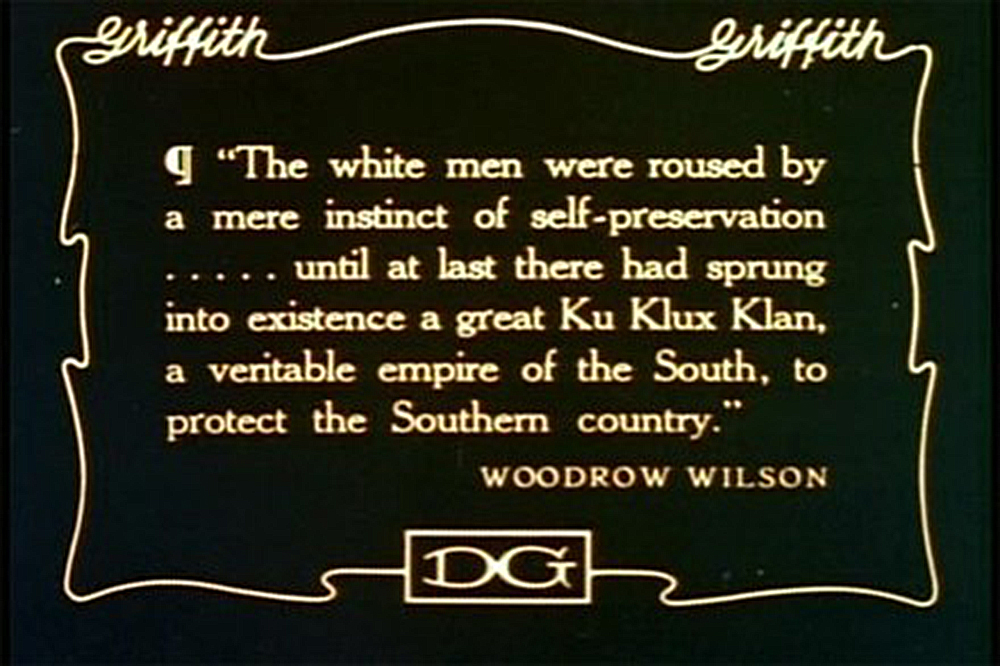

In a later scene, the white heroine (played by Lillian Gish) is threatened by a black man unable to contain his urge to “mongrelize” the white race. Before she is ravaged, a savior army rides in: The Ku Klux Klan. The title-card copy comes straight from the president’s five-volume History of the American People, published in 1902:

The white men were roused by an instinct of self-preservation…until at last there had sprung into existence a great Ku Klux Klan…to protect the Southern country.

The newly formed NAACP protested the film, to little effect. Filmgoers were dazzled by the film’s length (twelve reels instead of the usual six) and directorial breakthroughs by D.W. Griffith that changed the way movies were made: dramatic close-ups, fade-outs, a cast of hundreds made to seem thousands, the first music score written for a film, and sheet music to be played in sync with the reels, instead of letting movie-house pianists play what they wished.

Griffith accused protesters of intolerance and violations of freedom of speech. He was, however, persuaded to change the title of his film to the less inflammatory The Birth of a Nation. (The title conveyed the film’s underlying theme: former enemies reuniting in defense of “their Aryan birthright.”)

By 1915 the Ku Klux Klan had largely disbanded, but now that a movie had made heroes of its members, it revived, adopting the look that had been invented by the film’s set designers, who had used 25,000 yards of white muslin to outfit the cast in pointed hoods with eyeholes. Even the horses in The Birth of a Nation wore them.

The movie became a blockbuster, the biggest hit of the silent-film era, spurring merchandisers to hawk Ku Klux hats and kitchen aprons, theater ushers to dress in Klan robes for openings, and New York matrons to host KKK costume balls.

Ten years later, in 1925, a “modern” Ku Klux Klan marched in Washington, parading down Pennsylvania Avenue, thirty thousand strong, wearing the white robes and pointed hoods designed for the movie.

Want to read more? Here are some past posts from this series:

• Monica Muñoz Martinez, author of The Injustice Never Leaves You

• Tatjana Soli, author of The Removes

• John Wray, author of Godsend

• Imani Perry, author of Looking for Lorraine

• Ken Krimstein, author of The Three Escapes of Hannah Arendt: A Tyranny of Truth

• Katherine Benton-Cohen, historical adviser for the film Bisbee ’17

• Nicholas Smith, author of Kicks: The Great American Story of Sneakers

• Anna Clark, author of The Poisoned City: Flint’s Water and the American Urban Tragedy

• Christopher Bonanos, author of Flash: The Making of Weegee the Famous

• Elizabeth Catte, author of What You Are Getting Wrong About Appalachia

• Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing