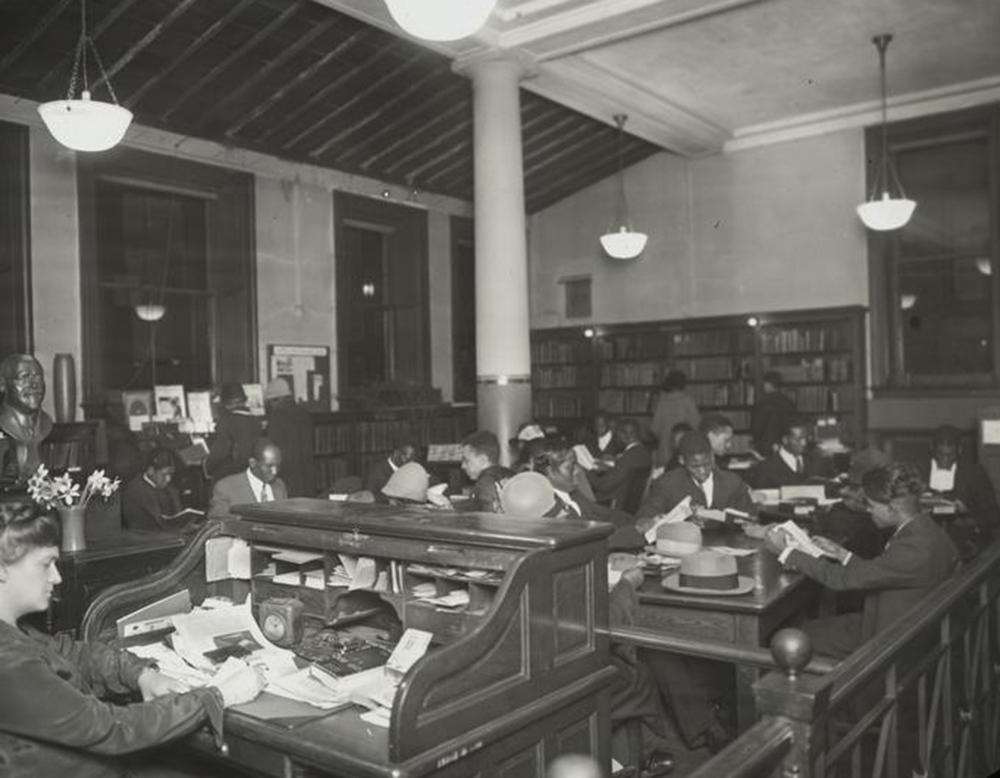

The 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library. The New York Public Library, Manuscripts and Archives Division.

Rain and books keep time in both of Nella Larsen’s novels, Quicksand (1928) and Passing (1929); many chapters begin with a note that the day is gray and damp—unless it is winter, when it is gray and cold—and her lonely characters pass the time between sessions of swampy, inescapable introspection about things they intend to ignore, avoid, or leave unsaid by heading to their bookshelves. The Harlem Renaissance novelist has faded in and out of focus over the years; her life, known in outline with little context left behind—along with the fact that she was a woman writing about women thinking about race—made it easier for history to forget her, although recent years have seen several biographies and an overdue obituary in the New York Times. Here is a list of books that flitted through her life.

Ten Books to Help You Become a Librarian

Nella Larsen was born in Chicago in 1891. Her mother was a white Danish immigrant, and her father was black. Little is known about him, and much of Larsen’s early life was spent mostly submerged in whiteness. After her mother married a white man, she eventually gave birth to Larsen’s sister, who, when told she had received $35,000 upon Larsen’s death, lied and said she didn’t have a half-sister. After stops at Fisk University in Nashville and the University of Copenhagen, Larsen eventually ended up in Harlem, the place that, thanks to biographical shorthand, would become her historical address. For five years, she worked as a librarian at the 135th Street branch of the New York Public Library, in a building that now houses the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. David Levering Lewis writes in When Harlem Was in Vogue that “the intellectual pulse of Harlem throbbed at the 135th library.”

The branch supervisor was Ernestine Rose, a white librarian who managed to integrate her staff—and ensure that all black employees weren’t only assistants—while holding on to her mostly conservative ideas about race. Rose pushed Larsen to attend library school, and the future author became the first black woman to be admitted to the New York Public Library’s program. Rose writes in her book The Public Library in American Life that

if a person does not love books, why on earth should she, or he, wish to become a librarian? There is little enough in the way of financial reward, the hours are long, vacations short, and work is hard, though this the beginner may not realize. But a real love and knowledge of books and all the paraphernalia and attributes of the world of books does constitute a passport into librarianship, while if to that is added a genuine interest in people, the prospective librarian has gone a long way toward meeting the requirements of a good public librarian.

The NYPL application asked Larsen for a list of ten books she had recently read. George Hutchinson includes it in his book In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line:

Knut Hamsun’s Scandinavian classic, Growth of the Soil; Max Beerbohm’s And Even Now; Lothrop Stoddard’s New World of Islam; Julian Street’s Abroad at Home; B.L. Putnam Weale’s Fight for the Republic in China; Lytton Strachey’s controversial modernist psycho-biography Queen Victoria; H.L. Mencken’s Prejudices (1 and 2); Hendrik Van Loon’s Story of Mankind (a bestselling, often satirical history of the world, written for children but immensely popular even with “highbrow” adults); Hamlin Garland’s Midwestern realist classic A Daughter of the Middle Border; and W.E.B. Du Bois’ scathing modernist hybrid memoir and indictment of white America, Darkwater.

She also listed many magazines—Bookman, Literary Digest, Asia, The Nation—and two now defunct newspapers, the Tribune and the Evening Post. Larsen also told the library she hoped would want her that she had just begun reading Library Journal.

The entrance examination to the school was lengthy and required much studying, Thadious M. Davis explains in her book Nella Larsen: Novelist of the Harlem Renaissance.

Her preparation for the examination disciplined and directed her reading. She expanded her range of interests and, quite possibly, her interpretive abilities. This experience of intense reading became one of her most valuable preparations for becoming a novelist, and it helps to explain the rich literary texture of her writing, which was different from the reticence of her speech. “Reading is a silent, private activity,” Elizabeth Flynn has observed, “and so perhaps affords women a degree of protection not present when they speak.”

Marmaduke Pickthall

Near the beginning of Quicksand, Larsen’s somewhat autobiographical novel, protagonist Helga Crane—born to a white Danish immigrant mother and a black father—reads a book by Marmaduke Pickthall called Saïd the Fisherman. The novel was Pickthall’s first; he was best known for traveling through the Middle East, translating the Quran into English, and publicly converting to Islam after a talk at the Muslim Literary Society in Notting Hill. The novel, set in Egypt, with a spiritually driven protagonist who will die by the book’s end, was enjoyed by H.G. Wells enough that he sent the author a letter that proved less than prophetic after finishing it: “I wish that I could feel as certain about my own work as I do of yours, that it will be alive and interesting people fifty years from now.”

Saïd the Fisherman was recommended to Larsen by her close friend Carl Van Vechten, the white photographer Lewis calls “white America’s guide through Harlem.” When Van Vechten’s fifth novel was published in 1926, Larsen gushed to him that her husband Elmer “thinks it shows the same understanding and deep insight as Saïd the Fisherman.” The terribly titled N----- Heaven—a slang term for the segregated balcony in theaters and churches—was despised by Countee Cullen and Ralph Ellison. James Weldon Johnson’s secretary Richetta Randolph wrote, per Lewis, “What Mr. Van Vechten has written is just what those who do not know us think about all of us.” No one was quite as effusive as Larsen—“It’s too close, too true, [it’s] as if you had undressed the lot of us and turned on one strong light”—but other prominent black writers, including Langston Hughes and Johnson, also said that they enjoyed the book. (“The book and not the title is the thing,” Johnson would insist.)

The novel is short, Kelefa Sanneh wrote in The New Yorker,

made shorter still by its stand-alone prologue, about a pimp known as the Scarlet Creeper, and by its split structure, which pairs two slim novellas, one for each protagonist. The first is given over to Mary Love, a perceptive but anxious young librarian; the second belongs to Byron Kasson, a stubborn and confused aspiring writer, whose brief love affair with Mary provides a hinge between the two halves. Both characters wrestle with Negro identity: Mary is too self-conscious to join the revelry she sees all around her in Harlem, while Byron is paralyzed and enraged by the humiliations of a segregated city. After a condescending white editor criticizes Byron’s work, he leaves Mary and takes up with a debauched socialite named Lasca Sartoris; when Lasca leaves him, he descends into fury, and the novel ends with a complicated spasm of violence. (It was Mr. Scarlet, in the night club, with the revolver—though it’s Byron who faces punishment.)

Mary is a librarian, just like Larsen used to be, Hutchinson notes.

Mary is likely a composite, but the contents of her bookshelf are Nella Larsen’s: James Branch Cabell, Anatole France, Jean Cocteau, Louis Bromfield, Aldous Huxley, Sherwood Anderson, Somerset Maugham, Elinor Wylie, James Gibbons Huneker, and inscribed copies of James Weldon Johnson’s Fifty Years and Other Poems, [Jean] Toomer’s Cane, [Claude] McKay’s Harlem Shadows, [Walter] White’s The Fire in the Flint, Du Bois’ Souls of Black Folk, Jessie Fauset’s There Is Confusion. On her writing table are books from the library “to keep abreast of the modern output.”

The New York Telegram’s Mary Rennels, interviewing the author shortly after Passing’s publication, writes that Larsen claimed John Galsworthy—author of The Forsyte Saga—and Van Vechten as her favorite authors, “the latter to some of us is a savior, to others a devil.” The novel, which appeared three years after Van Vechten’s most controversial work, was dedicated to him.

Anatole France

At the end of Quicksand, Helga Crane, suffering from postpartum depression and an accumulation of other pains and regretted choices, asks her nurse to read from a book high up on a shelf in the next room. It contains a short story by the nineteenth-century French poet Anatole France, “The Procurator of Judea.” The chapter ends with the last line of the story, delivered by Pontius Pilate: “ ‘Jesus?’ he murmured, ‘Jesus—of Nazareth? I cannot call him to mind.’ ” Her devout nurse, perplexed, decides the tale is dull. Crane, meanwhile, “had slipped into slumber while the superbly ironic ending which she had so desired to hear was yet a long way off.”

Langston Hughes

The epigraph to Quicksand comes from Langston Hughes’ poem “Cross”:

My old man died in a fine big house.

My ma died in a shack.

I wonder where I’m gonna die,

Being neither white nor black?

In 1930 the poet published his debut novel, Not Without Laughter, a portrait of black life in Kansas, a setting not too distant from Joplin, Missouri, where Hughes was raised. The New York Times reviewed it, deciding that

Hughes, in fact, is the first of contemporary Negro writers to treat successfully with the life of the lower-class Negro in town as well as city. Claude McKay in Home to Harlem dealt with bottom-rung Negro life in its urban forms, as also did Rudolph Fisher in The Walls of Jericho. Hughes, however, in turning to the country for his setting has exploited material that is even more picturesque. More than that, he has come closer grips with this material than have his white contemporaries. In other words, he has made it live as itself, without resort to artifice or literary stratagem.

Nella Larsen wrote to Hughes after she finished it.

I read Not Without Laughter some ten days ago and have been intending to get the letter off ever since. But it’s been too hot to hold a pen. And I “seen” your picture in the paper Sunday. You have done what I always contended impossible. Made middle-class Negroes interesting (or any other kind of middle-class people). And your prose is lovely.

Walter White

Passing may be the best remembered novel of the 1920s that revolves around characters “passing” as white, but it definitely wasn’t the only one. Plum Bun: A Novel Without a Moral by Jessie Redmon Fauset came out the same year as Passing and tells the story of Angela Murray, who leaves her black neighborhood in Philadelphia and heads to New York City, where she decides to pass as white while attending art school. In 1926, Walter White, future executive secretary of the NAACP—who later wrote a memoir titled A Man Called White—published his second novel, Flight, which also features a light-skinned protagonist who passes.

After reading a review of the book in the National Urban League publication Opportunity, Larsen wrote to Charles S. Johnson, the magazine’s editor, to list her objections to the reviewer’s criticism of Flight, using books she had read recently to bolster her argument.

I come now to your reviewer’s complaints about the author’s style. He grumbles about “lack of clarity,” “confusion of characters,” “faulty sentence structure.” These sins escaped me in my two readings, and even after they had been so publicly pointed out, I failed to find them. Even the opening sentence, so particularly cited, still seems to me all right. But then, I have been recently reading Huysmans, Conrad, Proust, and Thomas Mann. Naturally these things would not irritate me as they would an admirer of Louis Hémon and Mrs. Wharton. Too, there’s Galsworthy, who opens his latest novel with a sentence of some thirty-odd words.

Sheila Kaye-Smith

Later in 1930, Larsen went to Europe on a Guggenheim Fellowship. By the time she returned, her career was crumbling. Larsen’s short story “Sanctuary,” published in the magazine Forum before she left, is her last published work. Davis quotes writer Harold Jackman’s January 1930 letter to Countee Cullen about the story:

It has been found out…that it is an exact blueprint of a story by Sheila Kaye-Smith called “Mrs. Adis,” which is in a book called Joanna Goodens Marries and Other Stories. The only difference is that Nella has made a racial story out of hers, but the procedure is the same as Kaye-Smith’s, and…the dialogue in some places is almost identical.

Darryl Pinckney wrote of “Sanctuary” in 2002 that

it is better than “Mrs. Adis” by Sheila Kaye-Smith, the story, published in Century magazine in 1922 and set in nineteenth-century Sussex, that Larsen was accused of plagiarizing. But a comparison of the two makes Larsen’s explanation for the similarities—that the plot was common in Negro folklore—unconvincing. In any case, she never published the novel she’d gone to Europe to write.

Larsen said that she heard the story from a patient during her time as a nurse at Lincoln Hospital in Harlem between 1912 and 1915, before the publication of “Mrs. Adis,” adding that “it seems to me that anyone who intended to lift a story would have avoided doing it as obviously as this appears to have been done.”

In the years since, her defenders have said that she might have inadvertently lifted the plot during her years of absorbing words at the library—or that her short story was a bit of modernist experimentation, appropriating the plot of a white writer after watching generations of black writers enduring the reverse—but these retrospective assessments don’t change the end of Larsen’s story. She never published another word.

Read the other entries in our reading list series: Julia Ward Howe, Walt Whitman, Willa Cather, Virginia Woolf, Frederick Douglass, Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roosevelt, Flannery O’Connor, and Emily Dickinson.