Emily Dickinson, c. 1846. Amherst College Archives & Special Collections.

As much as Emily Dickinson is falsely portrayed as a recluse, her letters and reading habits show that she was constantly absorbing the world and transposing it into her poetry between en dashes. For all of those who have ever thought, “I wish a dead poet could recommend books to me” (this is probably a short list of people), here is a reading list drawn from some of the writers and books Dickinson mentioned most in her letters, or according to those who knew her.

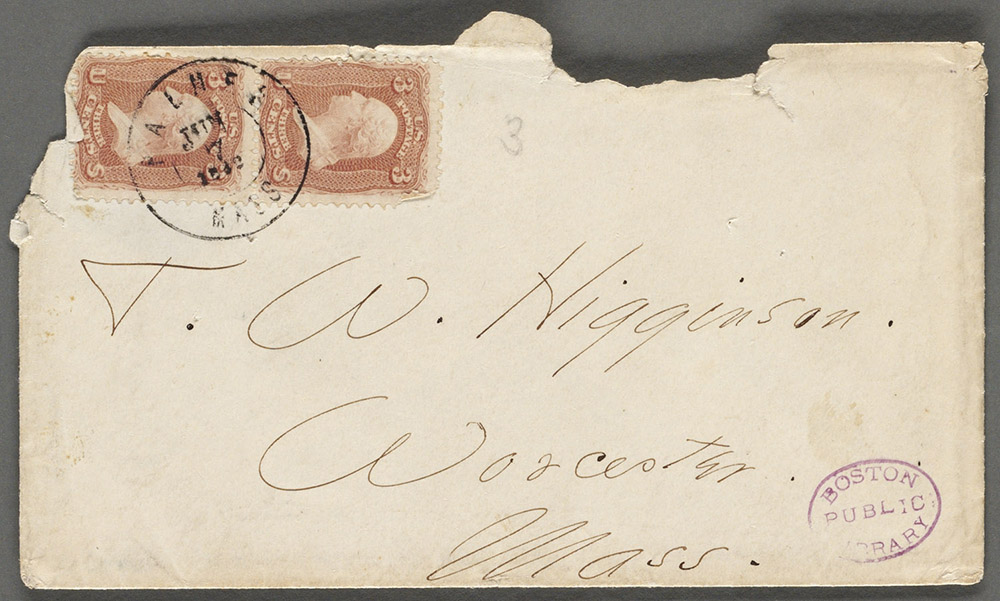

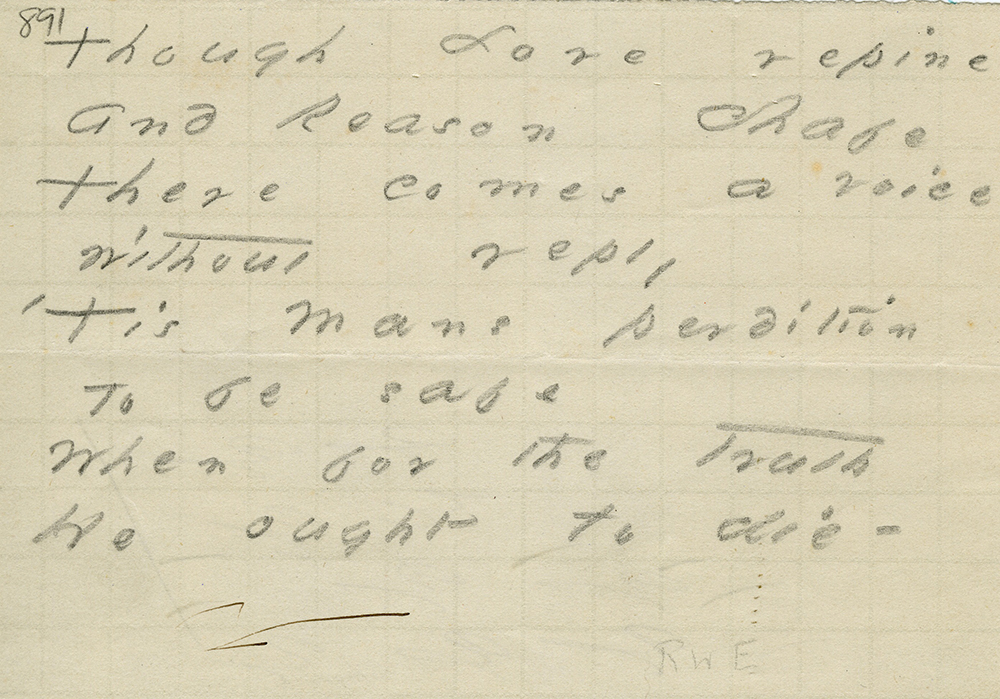

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

After Dickinson died in 1886, Thomas Wentworth Higginson—an abolitionist who, like Robert Gould, commanded a black regiment in South Carolina during the Civil War—described their decades-long correspondence in The Atlantic. She first wrote to him after he published lessons for young authors in the same magazine. Her short note began, “Are you too deeply occupied to say if my Verse is alive?” Over the years, the pair often swapped reading recommendations. She sent him a copy of Daniel Deronda, telling him that “to abstain from [the book] is hard.” (A picture of Mary Ann Evans hung in Dickinson’s room, and she often gushed about how much she loved the woman who wrote under the pen name George Eliot.) He, in turn, recommended the short story “Circumstance,” written by another one of the female authors he championed, Harriet Prescott Spofford.

After devouring it, she wrote him that “it followed me in the dark, so I avoided her.” In the same letter, she spoke of Whitman: “I never read his book, but was told that it was disgraceful.” She also often read Higginson’s own work. His first book, Outdoor Papers, she told him “is still as distinct as Paradise…It was Mansions – Nations – Kinsmen – too – to me.” Dickinson was perhaps flattering him a bit—she often did so, as Brenda Wineapple notes in White Heat: The Friendship of Emily Dickinson and Thomas Wentworth Higginson. But she kept reading his work and commenting on it. After the poet died, her own work was finally published, thanks in part to Higginson, who oversaw the death of many of the dashes essential to her art. It took decades before the public saw her words in the same pristine condition as Higginson did as they were first sent to him in the post.

The Complete Works of Shakespeare

After her eye troubles, potentially the result of inflammation from iritis, ended in 1865, Dickinson told several friends that she broke her reading fast with Shakespeare. “While Shakespeare remains,” she wrote to Higginson, “Literature is firm.” She lived at a time when few women were encouraged to read the playwright; as one writer put it, according to Emily Dickinson’s Shakespeare, abstaining might “keep out of the mind some rare and happy thoughts,” but it also “will keep out of the heart an unholy influence.” Less than perturbed by the dangers, Dickinson kept reading. Her niece Martha Dickinson Bianchi once wrote of Emily’s reading habits: “Shakespeare always and forever; Othello her chosen villain, with Macbeth familiar as the neighbors and Lear driven into exile as vivid as if occurring on the hills before her door.” The Dickinson family’s copy of The Complete Works of Shakespeare backs her up when you tally up the marginalia within; Othello is marked up the most. On page 292 of Volume 5—which is dog-eared—the part in Act III where Othello says,

I will deny thee nothing:

Whereon, I do beseech thee, grant me this,

To leave me but a little to myself.

is highlighted in pencil. In one of the last letters she ever wrote, Dickinson quoted Romeo and Juliet to her aunt: “‘I do remember an Apothecary,’ said that sweeter Robin than Shakespeare, was a loved paragraph which has lain on my Pillow all Winter…”

The Bible

The Word was the well Dickinson drew from most. She received her first Bible from her father at age thirteen, after years of attending services with her Calvinist family at Amherst’s First Congregational Church. She told Higginson in 1840 that her father “did not wish [his children] to read anything but the Bible.” However, she eventually stopped going to church, preferring not to profess her faith in public, as required by the times. The religious text that underpinned the waves of revival undulating across the country stuck around, however, if not as a guide, at least as literary fodder, reappearing in her letters and verse. “Excuse my quoting from the Scripture,” she wrote to her Amherst Academy friend Abiah Root on September 10, 1845, near the beginning of her teenage religious rebellion, “for it was so handy in this case I couldn’t get along very well without it.” Her personal copy of the Bible, available to view online, is filled with evidence of Emily’s hand. Half a page in Job has been clipped out, disappearing the lines near “Hath the rain a father? Or who hath begotten the drops of dew?” and “Behold, I am of small account; What shall I answer thee? I lay my hand upon my mouth.” A flower was once pressed between the pages of Psalms, and page 241 of the Revelation of St. John the Divine has been dog-eared.

Representative Men

In 1876 Dickinson sent Representative Men, a collection of seven lectures given by Ralph Waldo Emerson, to Thomas Wentworth Higginson’s wife as a Christmas present. “I am bringing you a little Granite Book you can lean upon,” she wrote, describing the sturdy weight of the text with her trademark literary efficiency. In 1882 she brought the Transcendentalist up in another letter to Otis Philip Lord: “Today is April’s last – it has been an April of meaning to me. I have been in your Bosom. My Philadelphia [Charles Wadsworth] has passed from Earth, and the Ralph Waldo Emerson – whose name my Father’s Law Student taught me, has touched the secret Spring. Which Earth are we in?” Emerson lectured at Amherst College several times during Dickinson’s life and occasionally dined at her brother’s house, but it’s not clear if she ever heard him speak. All seventeen copies of Emerson’s books owned by members of the Dickinson family are marked up liberally, so the speeches were at least digested by them, if not transmitted aurally.

“No Coward Soul Is Mine”

In the Dickinson family’s copy of the poems of Currer, Ellis, and Acton Bell—remembered now as the Brontë sisters—there is a big X next to the words “The following are the last lines that my sister Emily ever wrote.” The poem that follows, “No Coward Soul Is Mine,” was allegedly chosen by another Emily to be read at her funeral. Dickinson called Emily Brontë “gigantic.”

Elizabeth Barrett Browning

“Should anybody where you go, talk of Mrs Browning,” Dickinson wrote to Springfield Republican editor Samuel Bowles before his trip to Italy in 1862, “you must hear for us, and if you touch her grave, put one hand on the head, for me—her unmentioned mourner.” Dickinson unsurprisingly vacuumed up contemporary verse, enjoying near peers who had published when she had not. Elizabeth Barrett Browning was perhaps her favorite, judging from the fact that a portrait of the poet hung in her room. In fact, she had more than one portrait, as she told Higginson: “Have you the portrait of Mrs Browning? Persons sent me three – If you had none, will you have mine?” Dickinson praised Barrett Browning in her work: “I went to thank her,” for example, imagines a trip to her idol’s grave, and, after the poet died in 1861, she wrote, “Silver perished with her tongue.”

Kavanagh

Dickinson did not inherit her love of literary experimentation from her father, who once got angry with Austin and Emily after they read Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s novel Kavanagh in secret—her brother had stashed it away from view under the piano lid. The book is mostly unknown to posterity, although Dickinson often referenced it in letters. A literary manifesto hidden within may have resonated with Dickinson: “In a word, we want a national literature altogether shaggy and unshorn, that shall shake the earth, like a herd of buffaloes thundering over the prairies!”

Read the other entries in our reading list series: Julia Ward Howe, Walt Whitman, Willa Cather, Virginia Woolf, Frederick Douglass, Sylvia Plath, Theodore Roosevelt, Nella Larsen, and Flannery O’Connor.