Two Women with Hats, by William H. Johnson, c. 1939. Smithsonian American Art Museum, gift of the Harmon Foundation, 1967.

This summer, Lapham’s Quarterly is marking the season with readings on the subject or set during its reign. Check in every Friday until Labor Day to read the latest.

Days after the end of the Civil War, the Black journalist Philip Alexander Bell, who began his career at William Lloyd Garrison’s newspaper the Liberator, founded the Elevator in San Francisco. Serving the largest Black population in the American West, the Elevator printed the motto equality before the law in its masthead and published many editorials on Black suffrage, which Bell continued writing until the ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment in 1870. California was not one of the twenty-nine states that passed the amendment, but that didn’t stop Black leaders in San Francisco from closing schools and businesses so that locals could celebrate, as Frank H. Goodyear described in his 1999 study of the Elevator’s advocacy for Black enfranchisement. Bell kept producing the newspaper until 1885, four years before his death.

Jennie Carter was a frequent correspondent for the newspaper, filing dispatches under the bylines Ann J. Trask and Semper Fidelis—while sometimes fudging her biographical details and increasing her age by two decades, perhaps to lend her added gravitas and an air of expertise (or further conceal her identity)—on politics and rural life from her home in Nevada County, California, where she moved to from either New Orleans or New York circa 1860, when she was around thirty. Bell knew Carter’s true identity, because he refused to publish work under a pseudonym unless he knew who was behind it. He also tipped off his readers on at least one occasion, writing in 1868 that “Mrs. Trask is ‘Semper Fidelis,’ and ‘Semper Fidelis’ is Mrs. Trask.” Not much is known about Carter’s life outside her columns, which are not entirely reliable given that she treated herself as a composite character. Even her maiden name is unknown, as Eric Gardner notes in the introduction to a 2007 collection of Carter’s work.

Yet no matter how ghostly her historical presence, she created undeniably vivid documents of the time. Among her subjects were local celebrations of the Emancipation Proclamation, which at the time were often held on January 1, the day Lincoln’s decree was issued, or August 1, Emancipation Day for former British colonies. Eventually June 19—the day in 1865 that enslaved people in Texas won their freedom—surpassed these dates as the most popular time to celebrate Emancipation Day. In 2021 Juneteenth became a federal holiday.

On January 17, 1873, Carter reported, “A friend in Marysville”—a city in nearby Yuba County—“told me he was opposed to a first of January celebration, believing we ought to let all recollection of former years die out.”

I have thought much of his words since, and I must say I think them altogether wrong. It is an established fact that our appreciation of everything is commensurate with its cost, and our fathers well understood that fact, and so gathered every item of the great struggle that gave America her independence, gave it to us in history—for our schools, in paintings, for our parlors and monuments for our public squares, and still fearing or forgetful they even keep the great anniversary day, July 4th. And decreed it should be celebrated by American citizens to all coming time. Now have we not more to remember than they? What was the oppression of the British yoke compared to slavery, taxation to stripes? Was there ever anything so unhuman, so devilish as American slavery? Could the graves of its victims open and their dead come forth—think you they would say, “Cease to remember”? No! Their words would be “Cry aloud to your children, and let children’s children never forget what liberty cost, never forget Emancipation Day.”

Below is one of Carter’s earliest contributions to the Elevator, published on August 30, 1867, under the Ann J. Trask byline. One of the paper’s running jokes involved Bell mislaying his eyeglasses; Carter joined the game by poking fun at his forgetfulness in her letter to him.

Letter from Nevada County

Mud Hill, August 20

Mr. Editor: I have been repeatedly asked “how I have preserved summer in my heart all through my sixty years.” Hoping my experience may benefit others, and especially the children, I note a few facts.

In the first place, I had a childhood (which many children do not have nowadays). I did not assume a young lady’s position in society until I was somewhat prepared by years. Yes, I absolutely played with dolls when I was fourteen years of age; and one time a gentleman called to see me and I fled with my family of dolls to the attic and hid myself.

When a child I was very fond of reading, and read many things which now afford me great pleasure, for I am now living my youth over again by the aid of memory. I still read a great part of my leisure time, when I can keep my spectacles in sight. (By the by, Mr. Editor, have you found your spectacles? I will tell you where I found mine yesterday. After searching the house over, I found them perched above my eyes.)

In youth I was passionately fond of music, and today I can make music to suit myself. I cannot sing in operative style, although I get off some very good shakes.

I never drank tea, coffee, or wine—nothing stronger than water. I believe that is the reason why my face is so free from wrinkles. I awake in the morning feeling all right—not like many old ladies, cross until they get their tea, and many men so like bears their children run away from them until they get their bitters. Some women and children cannot get out of bed until they have got a cup of coffee.

I rise early. Summer and winter I am up at five, and endeavor to get to bed early. I try to “live peaceably with all” and preserve a good conscience; then I can sleep as soon as my head rests upon the pillow.

I am not the least dignified. I can play with the children today at hide-and-seek, or skip rope, and enjoy myself with them, and at times I almost forget my years and am only reminded of age by looking at my spectacles and not being able to see well without them.

I have always tried to be cheerful, able to give and take a joke, and have found a good laugh better than drugs from apothecaries.

I have always had a firm reliance on Providence, and although God has sorely tried me—separating me from many loved ones—I firmly believe it is all for the best, and when time shall end we shall all “walk the golden streets” together in “a city not made with hands, eternal in the Heavens.”

I have done a great many things through my life I should like to undo, and think if I could live my sixty years over again I could improve. I am endeavoring to grow “wiser and better as life wears away.”

In my childhood an old man told me if I would observe three things I would enjoy good health. I will say they proved useful to me, and may others who read your paper. First, keep the head cool and calm. Second, keep the feet dry and warm. Third, keep the heart free from anger.

Now, Mr. Editor, you have quite enough of this. Old ladies are garrulous, and I am no exception. I hope you will come and see us. Peaches are ripe, and we have an abundance, and would be pleased to extend to you our hospitality.

—A.J.T.

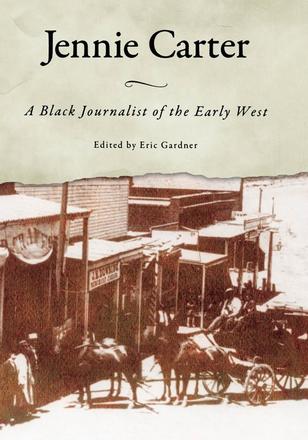

Letter excerpted from Jennie Carter: A Black Journalist of the Early West, edited by Eric Gardner. Copyright © 2007 University Press of Mississippi. Reprinted by permission of University Press of Mississippi.

Read the other entries in this series: Charles Dudley Warner, I.A.R. Wylie, Virginia Woolf, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Willa Cather, Thomas Jefferson, Fridtjof Nansen, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Izumi Shikibu, Hilda Worthington Smith, Mark Twain, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and William James.