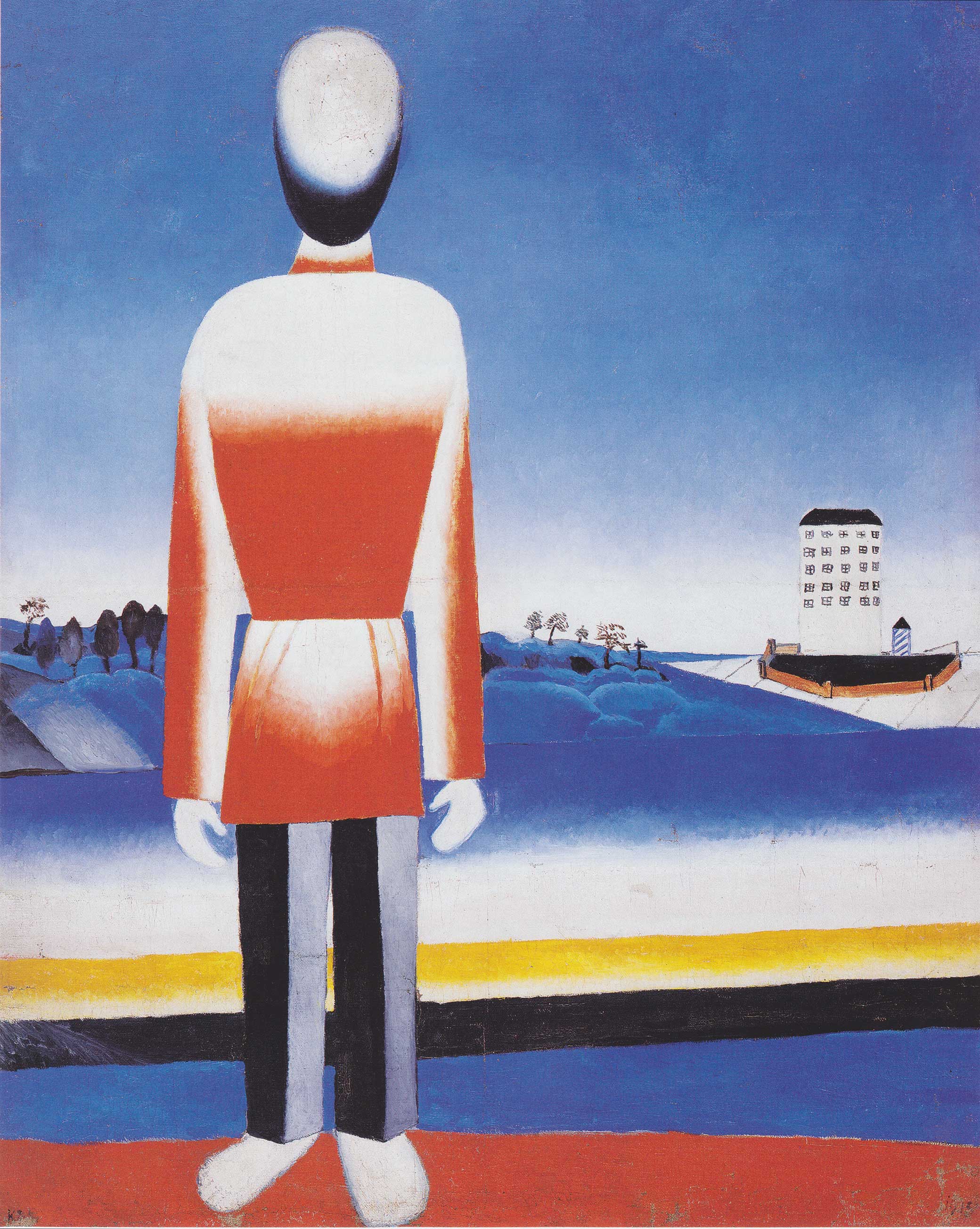

Man in Suprematist Landscape, by Kazimir Malevich, c. 1930. Wikimedia Commons.

This summer, Lapham’s Quarterly is marking the season with readings on the subject or set during its reign. Check in every Friday until Labor Day to read the latest.

The House of the Dead begins with its narrator, Aleksandr Petrovich Goryanchikov, already dead; his memoirs of ten years of hard labor in Siberia after being convicted of murdering his wife were found and published by an acquaintance who met Goryanchikov after his release. “The voice we hear,” the critic John Bayley wrote in 1987, “is thus disembodied, as if it came from under the floorboards of the huts, where the reader too feels himself to be. Unlike any other gulag book, and there have since been so many, The House of the Dead does not take us on a conducted tour, but seems to set up its horrors inside ourselves, to start and to finish there.” The novel was autobiographical, written after Fyodor Dostoevsky had spent four years imprisoned in a Siberian labor camp in the 1850s.

“I won’t even try to tell you what transformations were undergone by my soul, my faith, my mind, and my heart in those four years,” Dostoevsky wrote to his brother Mikhail in 1854 after his release—which also marked the start of his compulsory military service in Siberia.

It would be a long story. Still the eternal concentration, the escape into myself from bitter reality, did bear its fruit. I now have many new needs and hopes of which I never thought in other days. But all this will be pure enigma for you, and so I’ll pass to other things. I will say only one word: Do not forget me, and do help me. I need books and money. Send them me, for Christ’s sake…We shall see one another someday, brother. I believe in that as in the multiplication table. To my soul, all is clear. I see my whole future, and all that I shall accomplish, plainly before me. I am content with my life. I fear only men and tyranny.

Near the end of The House of the Dead, Goryanchikov reflects on how the arrival of summer makes him and his fellow convicts dream of escape, longing for a chance to “change their lot.”

We set about our summer tasks. The sun becomes hotter and more brilliant every day; the atmosphere has the spring in it, and acts upon our nervous system powerfully. The convict, in his chains, feels the trembling influence of the lovely days like any other creature; they rouse desires in him, inexpressible longings for his home, and many other things. I think that he misses his liberty, yearns for freedom more when the day is filled with sunlight than during the rainy and melancholy days of autumn and winter. You may observe this positively among convicts; if they do feel a little joy on a beautiful clear day, they have a reaction into greater impatience and irritability.

I noticed that in spring there was much more squabbling in our prison; there was more noise, the yelling was greater, there were more fights; during the working hours we would see a man sometimes fixed in a meditative gaze that seemed lost in the blue distance somewhere, the other side of the Irtysh, where stretched the boundless plain, with its flight of hundreds of versts, the free Kyrgyz Steppe. Long-drawn sighs came to one’s ear, sighs breathed from the depths of the chest; it might seem that the air of those wide and free regions, haunted by their thought, forced the convicts to draw deep respirations, and was a sort of solace to their crushed and fettered souls.

“Ah!” cries at last the poor prisoner all at once, with a long, sighing cry; then he seizes his pick furiously, or picks up the bricks, which he has to carry from one place to another. But after a brief minute he seems to forget the passing impression, and begins laughing, or insulting people near, so fitful is his humor; then he attacks the work he has to do with unusual fire, labors with might and main, as if trying to stifle by fatigue the grief that has him by the throat. You see they are fellows of unimpaired vigor, all in the very flower of life, with all their physical and other strength about them.

How heavy the irons are during this season! All this is not sentimentality, it is the report of rigorous observation. During the hot season, under a fiery sun, when all one’s being, all one’s soul, is vividly conscious of, and intimately feels, the unspeakably strong resurrection of nature going on everywhere, it is more difficult to support the confinement, the perpetual surveillance, the tyranny of a will other than one’s own.

Besides this, it is in spring with the first song of the lark that throughout all Siberia and Russia men set out on the tramp; God’s creatures, if they can, break their prison and escape into the woods. After the stifling ditch where they work, after the boats, the irons, the rods and whips, they go vagabondizing where they please, wherever they can make it out best; they eat and drink what they can get, ’tis all the time potluck with them; and by night they sleep undisturbed in the woods or in a field, without a care, without the agony of knowing themselves in prison, as if they were God’s own birds; their “Good night” is said to the stars, and the eye that watches them is the eye of God. Not altogether a rosy life, by any means; sometimes hunger and fatigue are heavy on them. Often enough the wanderers have not a morsel of bread to keep their teeth going for days and days. They have to hide from everybody, run to earth like marmots; sometimes they are driven to robbery, pillage—nay, even murder.

“Send a man there and he becomes a child, and just throws himself on all he sees”; that is what people say of those transported to Siberia. This saying may be applied even more fitly to the tramps. They are almost all brigands and thieves, by necessity rather than inclination. Many of them are hardened to the life, irreclaimable; there are convicts who go off after having served their time even after they have been put on some land as their own. They ought to be happy in their new state, with their daily bread assured them. Well, it is not so; an irresistible impulse sends them wandering off.

This life in the woods, wretched and fearful as it is, but still free and adventurous, has a mysterious seduction for those who have experienced it; among these fugitives you may find to your surprise people of good habit of mind, peaceable temper, who had shown every promise of becoming settled creatures—good tillers of the land. A convict will marry, have children, live for five years in the same place, then all of a sudden he will disappear one fine morning, abandoning wife and children, to the stupefaction of his family and the whole neighborhood.

One day, I was shown at the convict establishment one of these deserters of the family hearthstone. He had committed no crime—at least he was under suspicion of none—but all through his life he had been a deserter, a deserter from every post. He had been to the southern frontier of the empire, the other side of the Danube, in the Kyrgyz Steppe, in eastern Siberia, the Caucasus, in a word, everywhere. Who knows? Under other conditions this man might have been a Robinson Crusoe, with the passion of travel so on him. These details I have from other convicts, for he did not like talk, and never opened his mouth except when absolutely necessary. He was a peasant, of quite small size, of some fifty years, very quiet in demeanor, with a face so still as to seem quite without any sort of meaning, impassive almost to idiocy. His delight was to sit for hours in the sun humming a sort of song between his teeth so softly that five steps off he was inaudible. His features were, so to speak, petrified; he ate little, principally black bread; he never bought white bread or spirits; my belief is he never had had any money, and that he couldn’t have counted it if he had. He was indifferent to everything. Sometimes he fed the prison dogs with his own hand, a thing no one else was known to do (speaking generally, Russians don’t like giving dogs things to eat from the hand). People said that he had been married, twice even, and that he had children somewhere. Why he had been sent as a convict, I have not the least idea. We fellows were always fancying that he would escape; but his hour did not come, or perhaps had come and gone; anyhow, he went through with his punishment without resistance. He seemed an element quite foreign to the medium wherein he had his being, an alien, self-concentrated creature. Still, there was nothing in this deep surface calm which could be trusted; yet, after all, what good would it have been to him to escape from the place?

Compared with life at the convict prison, the vagabond age of the forests is as the joys of paradise. The tramp’s lot is wretched enough, but at least free. So it is that every prisoner all over the soil of Russia becomes restless with the first rays of the smiling spring.

Comparatively few form any settled plan for flight; they fear the hindrances in the way and the punishment that may ensue; only one in a hundred, not more, make up his mind to it, but how to do it is a thought that never ceases to haunt the minds of the ninety-nine others. Filled as they are with this longing, anything that looks like giving a chance of success is a comfort to them; then they set about comparing the facts with cases of successful escape. I speak only of prisoners after and under sentence, for prisoners not yet tried and condemned are much more ready to try at an escape. And those who have been sentenced rarely get away unless they attempt it in early days. When they have spent two or three years of their time, they put them to a sort of credit account in their minds, and conclude that it is better to finish with the law and be put on land as a free man rather than forfeit that time if they fail in escaping, which is always a possibility. Certainly not more than one convict in ten succeeds in changing his lot. Those who do are nearly always men sentenced to an extremely long punishment or for life. Fifteen, twenty years seem like an eternity to them. Then there is the branding, which is a great difficulty in the way of complete escape.

Changing your lot is a technical expression. When a convict is caught trying to escape, he is subjected to formal interrogatory, and will say he wanted to change his lot. This somewhat literary formula exactly represents the act in question. No escaped prisoner ever hopes to become a perfectly free man, for he knows that it is nearly impossible; what he looks for is to be sent to some other convict establishment, or to be put on the land, or to be tried again for some offense committed when on the tramp; in a word, to be sent anywhere else, it matters not where, so that he gets out of his present prison, which has become insufferable to him. All these fugitives, unless they find some unexpected shelter for the winter, unless they meet someone interested in concealing them, or if—last resort—they cannot procure—and sometimes a murder does it—the legal document, which enables them to go about unmolested everywhere; all these fugitives present themselves in crowds during the autumn in the towns and at the prisons; they confess themselves to be escaped tramps, pass the winter in jail, and live in the secret hope of getting away the following summer.

Read the other entries in this series: Charles Dudley Warner, I.A.R. Wylie, Jennie Carter, Virginia Woolf, Willa Cather, Thomas Jefferson, Fridtjof Nansen, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Izumi Shikibu, Hilda Worthington Smith, Mark Twain, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and William James.