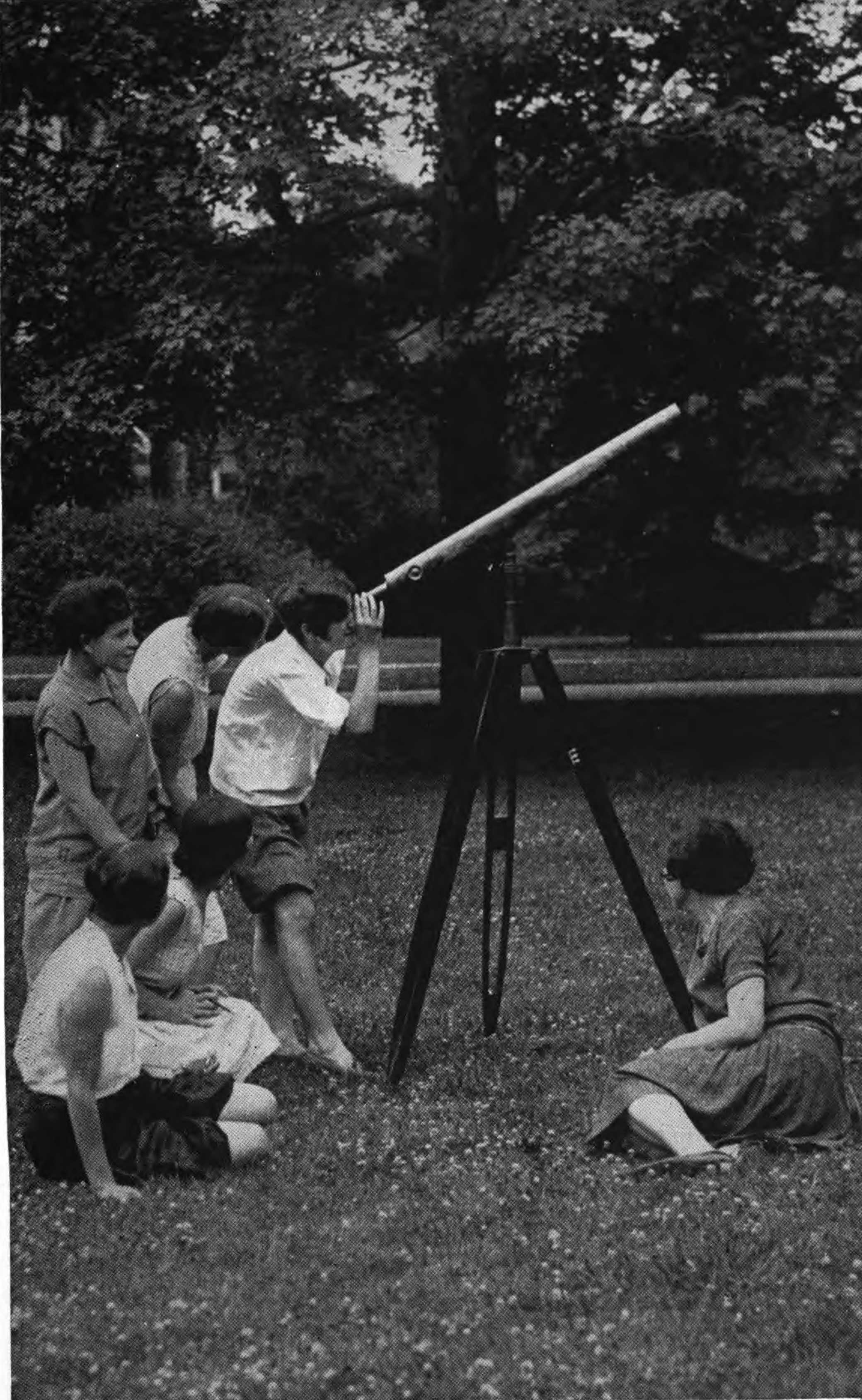

Photograph of students looking through a telescope at the Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry, from Women Workers at the Bryn Mawr Summer School, 1929. HathiTrust Digital Library.

This summer, Lapham’s Quarterly is marking the season with readings on the subject or set during its reign. Check in every Friday until Labor Day to read the latest.

The Bryn Mawr Summer School for Women Workers in Industry opened in June 1921, welcoming around eighty students to the college campus outside Philadelphia for eight weeks of instruction. M. Carey Thomas, Bryn Mawr’s president, had hired her former student Hilda Worthington Smith to serve as dean for the program, which aimed to provide factory workers access to an education that had nothing to do with their trade. “For this alone it has been worth losing eight weeks of pay and chancing the loss of my job!” one student said of her summer economics course. A few employers continued to pay students or forwarded money to families, but it seems most workers simply decided that the opportunity was worth the risk or had saved up enough money to make up for lost wages. A scholarship fund covered students’ on-campus expenses.

The school admitted its first Black students in 1926, overruling objections from administrators (including Thomas) at Bryn Mawr, which would not admit its first Black student until the following year. The student body included an increasing number of unionized workers over the years, which did not please college trustees like alumna Frances Hand, wife of the federal judge Learned Hand. The trustees found an excuse to evict the school from Bryn Mawr in 1934 after two summer school faculty members observed a farm strike in Seabrook, New Jersey. Economists Colston Estey Warne and Mildred Fairchild Woodbury had, according to historian Rita Heller, “gone to Seabrook as individuals and had taken few, if any, students. They had witnessed the use of tear gas against women and children, had spoken to strike protagonists, and had behaved as Good Samaritans calling in a doctor.” Heller wrote about the incident in her 1986 dissertation on the school’s history:

The strike crisis was the beginning of the school’s demise. The involvement of at least two faculty members as strike observers, and their subsequent identification in the Philadelphia Inquirer, enabled the college to allege a violation of a no-strike participation agreement with the school. This allegation was, at least, a “misunderstanding” as [Hilda Worthington] Smith always told it. At most it was a conscious distortion staged by Frances Hand giving the college the rationale to distance itself from an increasingly controversial institution…In the ensuing furor the facts were forgotten; instead the college and public understood that the school had participated in a celebrated communist strike. The 1934 session ended in a flurry of accusation with the college evicting it for 1935. [The school did not hold classes anywhere in 1935.] The college welcomed the school back for 1936–38 but for a variety of reasons the school was now past its prime.

Heller noted that Bryn Mawr was also in the middle of a fiftieth-anniversary endowment campaign in 1934: “Could the college raise funds from its capitalist constituency while harboring a school that encouraged radicalism?” The college clearly thought not.

In 1929 Smith had published Women Workers at the Bryn Mawr Summer School, which surveyed the program’s accomplishments and structure, as well as collecting students’ perceptions of the educational experiment. Near the beginning of the book she describes students arriving in June:

From the far West, these early arrivals, the Seattle, Portland, and Tacoma delegation, with a California representative reported on her way. As train after train comes in girls appear in the office: a group of New York garment workers; a Philadelphia milliner with her mother and two sisters who have come to see the college where Mary is to spend two months; the Southern group, timid and tired with their first experience of sleeping cars and night trains; two colored girls from Chicago, serene and well poised, but undoubtedly wondering in their own minds how they will be treated in the school; textile workers from New England, some with Scotch or Irish burrs; telephone operators from Cincinnati; a waitress from Colorado; Russians in khaki knickerbockers and blouses, who have hitchhiked to Bryn Mawr; Scandinavians from Minnesota; an Italian dressmaker rejoicing to find other Italian girls in the school, and hurrying off to telegraph her mother this reassuring discovery; Lithuanians, Poles, Pennsylvania Germans mingling in the halls with mountain whites from Kentucky, Canadians, Romanians, Czechoslovakians.

Later in the book, Smith describes the program’s curriculum in detail and gives space for students to rate their professors.

Science

The facts of the outdoors are unknown to most of the summer school students, and to become acquainted with the world they live in is an exciting process, furnishing new and startling facts. For a girl who has never seen a squirrel her first sight of one on the campus marks a red-letter day. “Picking bugs” is always an exciting occupation. As an instructor said when one student brought in a dead hornet, “She looked as if she had discovered an archangel.” Every tree is inspected by the eager nature study groups, and every song of thrush or robin calls for fresh comment. According to the instructors, the summer school is the only institution they know where a serious faculty meeting is stopped by a wild scramble for a june bug, a specimen anxiously awaited by the science department. A cocoon or a chrysalis in process of development is watched intently, even during assembly periods, and the first student to observe the emerging moth or butterfly soon gathers a crowd with her news. One student, on her way home after the school closed, returned from several stations up the line when she met a girl who told her her moth was coming out of its cocoon. It is a moving sight to see a city-born girl long handicapped by factory and home conditions come into the laboratory with a joyous look in her eyes and in her arms a great bunch of what she calls her “don’t forget-me-nots.”

That this new knowledge is not acquired without a series of mental adjustments on the part of many students is proved every year. The subject of the evolution of life brings many real shocks to girls who have never thought beyond the traditional story of creation. The story of the rocks, pictures of primitive man, and the development of animal life all present many new and unforeseen pitfalls to uninformed minds. “How did they take pictures of those prehistoric men?” asked one girl. “Evolution is one of my pet peeves,” said another. “It sounds so good that I have to believe it, but it goes against everything I have ever been taught.” On the other hand, the idea of gradual development in time is immediately applied by many girls to their own economic problems. At every point during a lantern-slide lecture on primitive man, there was a chorus of voices: “How long ago was that?” The instructor explained that she had been speaking of events hundreds of thousands of years ago. “It just shows you can afford to wait” was the comment of one student who had been expecting the millennium tomorrow. “What’s the labor movement to a hundred thousand years?” Bits of discussion from the science class float around the campus, many of them appearing from time to time collected by the editor of the humorous column in the school magazine:

“Since I looked through the telescope I am just disillusioned about the moon. Science has spoiled the moon for me.”

“Well, I tell you, I’m no mammal!”

“I liked everything in the museum but my own skeleton and that nearly killed me.”

English

English, oral and written, is another vital department in the life of the school. No student ever gets enough, and the reiterated demand for “more English” has become familiar in every faculty meeting or curriculum committee. Typical of the feeling on the part of the students was the passing comment of one girl overheard in a lonely corridor. “I want English,” she muttered to herself as she hurried along, “I need English, I must have English.” One girl writes, describing her difficulties, “It seems as if in making an outline the tutors have screwed down all the topic and summarizing sentences and have locked the screwdriver away out of reach.”

Each year more hours have been assigned to the English department, and an attempt made to add more instructors and tutors in order to provide for the varying needs of the students. This handicap in language is felt not only by the foreign-born girls, who have been struggling in night schools and evening classes, but also by many American-born workers whose previous schooling has been so inadequate that they are limited in any form of expression. Logical thought and clearness of expression are always emphasized over and above technical details of grammar and spelling. “What is it, and what of it?” are bywords in the English department, and to these two fundamental questions one student added another that shows the trend of classroom discussion: “What ought it to be?” It is always illuminating to realize the utter confusion of mind of any summer school English class at the beginning of each term, and correspondingly heartening to observe at the end that facts have emerged and have been sorted out into something like systematic thinking; that greater freedom of expression has brought increased confidence to many students and for the first time made them aware of their own powers; that, in a word, the English language has ceased to be a bugbear and has become to many a useful tool in the solution of everyday problems.

One student writes:

English composition helps us to think clearly. When we write a theme, we are taught to present reasons against as well as for a proposition. In this we train our minds to think on both sides of a question and get the other person’s point of view. Words are often misused because we do not know the real meaning of them. In writing in order to use the right words, we must first know what they mean. Take the word gorgeous, for instance: it means bright colored, or many colored, yet we look at a black dress and say, “Isn’t it gorgeous?”

Another student:

It has been argued that English composition would be of no use to the worker after leaving the school. We came here to study industrial problems and not to become writers. It is true we are here to study industrial problems, but we as workers have had industrial experiences that are an important contribution to the studying and the solution of industrial problems. If, however, we do not know how to express ourselves and make known to others our experiences, they will be of no use.

The public-speaking class is at first terrifying to many girls. It is surprising how knees can shake at the thought of a two-minute speech on a familiar subject in the friendly atmosphere of the classroom. In spite of previous help from patient tutors, and constant reassurances on the part of instructors and fellow students, the ordeal of that first speech casts a gloom over the best part of the week for many students. The girl who courageously marches up to face the class and without a complete breakdown struggles through those halting sentences deserves every bit of the hearty commendation given her by instructor and classmates.

“Did she make a point? If so, what was it?” These seem simple questions when asked in regard to such brief speeches, but the storm of discussion that follows brings out total disagreement among the listeners. Kindly criticism, analysis of strong and weak points in logic, structure, and expression do much in the course of two months, and this actual classroom practice is supplemented by practice in forums, at assembly meetings, and in the constant campus discussion. Irritation may be an aid to free expression, and when a girl finds herself in a minority, with her ideas of long standing trampled on and her prejudices held up to ridicule, it would be surprising if the most inarticulate student could keep quiet.

After the first few weeks, anger gives way to good-humored argument, and the girl who at first has been afraid to lift her voice in a crowd comes to the conclusion that her opinion is as good as anyone’s and that to express it is only fair to herself and to the groups she represents in her own community. On the other hand, the articulate girl who is sure of herself, and too sure of her own opinions, begins to realize that perhaps she has not secured all the facts to back these opinions; that other girls who disagree with her so violently may have other information; that a glib tongue is not the only thing needed to confound one’s adversary in an argument. So each group profits by contact with the other, and that first terrified classroom session becomes a forum of interested and fairly able speakers, eager to measure up to the standards set by the class itself.

One instructor hit upon a clever device for promoting understanding by means of her public-speaking classes. She explained to the whole class the functions of a chairman, that in introducing speakers and presiding she was supposed to create a favorable atmosphere for the speaker. She then appointed as chairman for one session of the class a girl from a southern YWCA and as speaker a Russian trade unionist. The chairman came in advance to the instructor with an inquiry as to what she could say in her introduction about the unions and their achievements. On the next day the chairman and the speaker reversed their functions. Again the chairman sought light on how she might create the atmosphere that would enable the speaker from the club to appear at her best, for, she said, “I don’t know one good thing about the YWCA.”

By such mutual processes of learning understanding is fostered. Words and their definitions are given a good deal of attention in many English classrooms. These definitions are laboriously looked up in dictionaries and textbooks and discussed with violent disagreement around the lunch table or in campus groups. “Conservative: a person of few ideas carefully expressed,” writes one girl, and another, evidently of the opposite opinion, defines a radical as “one going to extremes, continuing constantly, annoying others.” To build up a wide vocabulary in two months is difficult, but the desire to do this is often created in the English classes. And the importance of words, their beauty and their wealth of connotation, is for the first time brought into the consciousness of the summer school student.

One of them writes:

We open the dictionary anywhere and they pass before us: words that are meek, words that are haughty, pirate words, drab stay-at-home words, and merry words, the sad, drooping words, words that are carefree, words that are drudges; some with the color of many seas, others suggesting glamour of a faraway land; the noble words, the subtle words, others frank and bland, the creeping loathsome words, and the words of stately beauty.

Read the other entries in this series: Charles Dudley Warner, I.A.R. Wylie, Jennie Carter, Virginia Woolf, Fyodor Dostoevsky, Willa Cather, Thomas Jefferson, Fridtjof Nansen, Elizabeth Robins Pennell, Izumi Shikibu, Mark Twain, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, and William James.