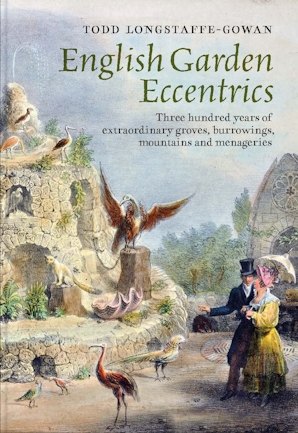

Rockwork, Lawn, and Camellia House at Hoole House from the Northeast, from the Gardener’s Magazine, 1838.

In the early 1860s the celebrated American horticulturist and landscape gardener Henry Winthrop Sargent, who had a “taste for horticultural oddities and freaks,” made a special pilgrimage to Hoole House in Cheshire to catch a glimpse of a garden which he had longed to see for over a quarter of a century. In his 1865 Impressions of English Scenery he remarked that he had been “astonished,” and his appetite whetted, by an 1838 article in the Gardener’s Magazine in which the landscape gardener and horticultural writer John Claudius Loudon supplied a “very elaborate account…of a visit he paid to Hoole House, near Chester, then belonging to Lady Broughton.” Sargent was determined to ascertain if the house still existed, “and if so, where was it, and did the rock garden still exist…?”

On leaving the gardens at Eaton Hall to set off on his journey, Sargent asked three gardeners and the landlord at his hotel whether they could direct him to Hoole. None had ever heard of it. Finally, an “old cabman” recollected the whereabouts of Lady Broughton’s house in the Liverpool Road. After “much trouble” Sargent discovered what he believed to be his destination—a garden with “a short but exceedingly well-kept avenue, the verges and sides beautifully cut, and densely planted with large masses of rhododendrons, laurel, yews, deodars, araucarias, all, except the araucarias, being closely clipped.” He observed that “this formal treatment of the trees augured favorably for the rock garden, but I saw no evidence of it.” After venturing further into the pleasure ground he met an “old gardener striking some geraniums,” who informed him that the garden he was seeking still flourished and was “kept up just as Lady Broughton had left it…when he had helped build and unbuild it (as a young man) as Lady Broughton was continually altering it.” Having been granted permission to see the garden, Sargent was led up to the house and through a small postern immediately adjoining the front entrance, whereupon, he exclaimed, “a perfect scene of enchantment suddenly broke upon”:

Imagine a little semicircular lawn, of about half an acre, of most exquisite turf, filled with twenty-eight baskets, about six feet in diameter, of the most dazzling and gorgeous flowers. Each basket a complete bouquet in itself, of three different colors, in circles; for instance, the lower circle would be coleus, the second, yellow calceolaria, the third, or upper, white-leaved geranium. On the top, as a sort of pinnacle, a group of scarlet gladiolus…These twenty-eight baskets seemed a succession of circular terraces, each color was so vivid, so gay, and so continuous.

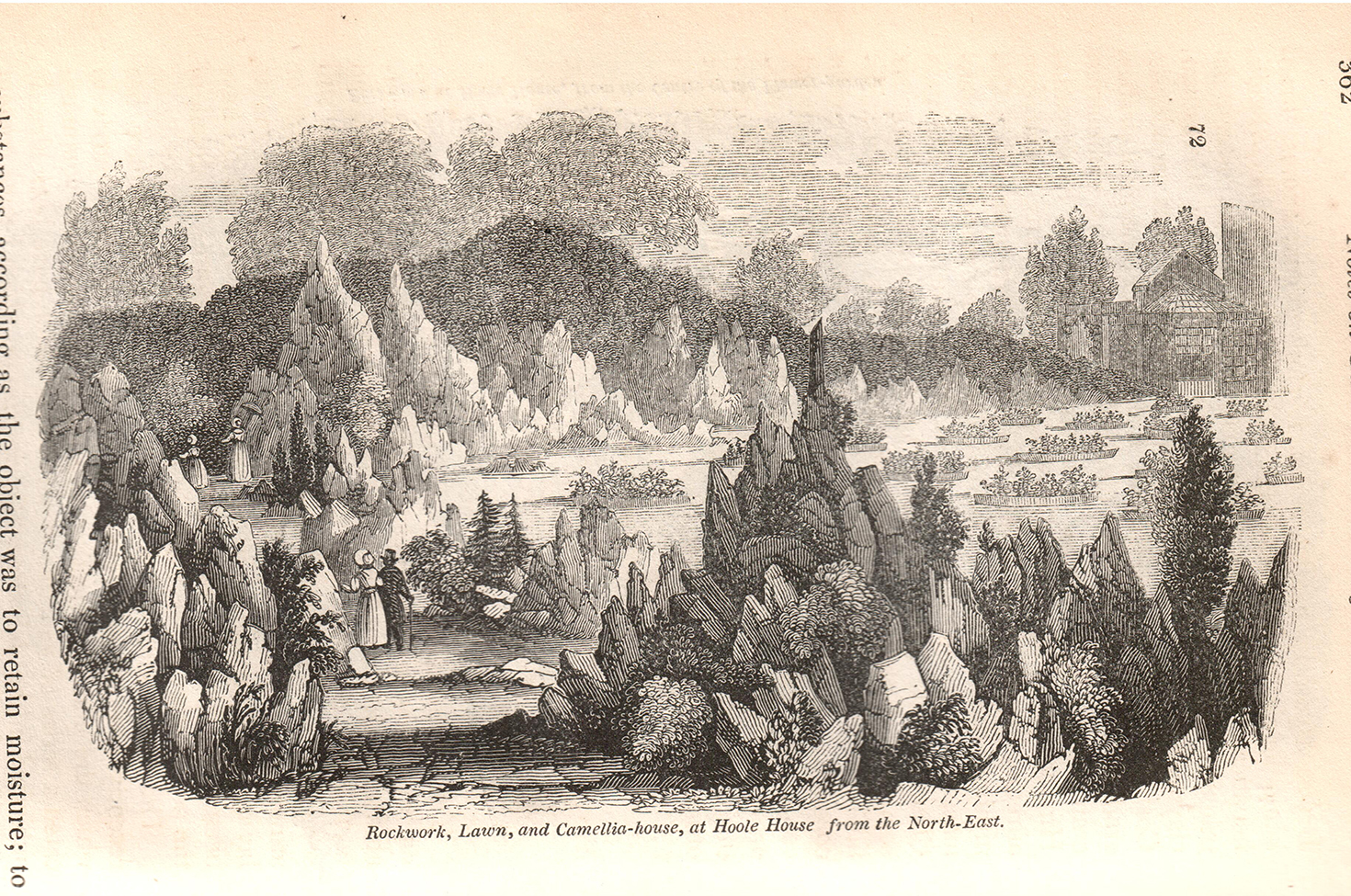

This “bright parterre” was laid out upon an emerald lawn that was surrounded by the famous rockwork, which ranged “from fifteen to thirty feet high, built up against the stables and offices, as support, and brought down irregularly to the lawn in front, filled with every variety of fern and rock plant that would stand the summer climate of England; most of the more delicate being removed in winter to green and even orchidaceous houses.” The visitor was overwhelmed:

I thought nothing could have been gayer than the twenty-eight circular beds, until I looked up and saw a much more gorgeous scene in this semicircle of rock, thirty feet high, crammed to overflowing, with every sort of palm, cactus, cereus, yucca, gladioli, geranium, etc. etc., in full flower, interspersed with deodars, clipped into pyramids, Irish yews, golden yews, abies cephalonica, pinsapo, normandiana, etc., all clipped into pyramids. The object being not only to keep them in harmony in size, with the rocks and the garden, but in appearance; since the highest pinnacles were intended to represent the Alps, for which purpose white spar was used to represent the glaciers and snow peaks, and small pinus cembra (the pine of the Alps) were interspersed along the edges, and near some yawning crevice, over which Alpine rustic bridges were thrown; through the whole of this rich and intricate maze ran a little wild path, bordered with heath and furze and broom, which crept up the rocky sides of the cliffs, among the wild distorted-looking firs, some eight to fifteen feet high, though thirty years old many of them, until they disappeared among the icy summits, apparently, of the Alpine heights.

Sargent concluded his account by affirming that “the whole thing was an extraordinary caprice, wonderfully carried out, and admirably described and illustrated, if I remember at this distance, by Mr. Loudon.” Loudon was certainly impressed by the tout ensemble when he made his first visit to Hoole in July 1831, and had been “exceedingly desirous of giving some account of it” in the Gardener’s Magazine. He could not, however, then “prevail on Her Ladyship to accede to our wishes.” Although Loudon professed that the garden was then “very perfect,” it is likely that the owner was of the opinion that it was still a work in progress.

Hoole House had become the home of Lady Broughton—born Elizabeth Egerton in 1771—in 1814, after she had become estranged from her husband, Sir John Delves Broughton, 7th Baronet. It was then a “modern mansion,” and Dame Eliza, as people came to title her, had only begun creating her garden in the 1820s.

In 1838 Loudon renewed his application, having seen some “exquisitely beautiful watercolor drawings (by Mr. Pickering of Chester) of the flower garden and rock fence.” This time Lady Broughton “reluctantly consented,” supplying Loudon with original drawings by “Mr. Harrison of Chester, the late celebrated architect” for the veranda, geranium house, greenhouse, and conservatory, and permitting him to take a general plan and views of the garden for publication. Loudon was delighted, and told his readers that the flower garden “has been by far the most celebrated garden of the kind in that part of the country for the last ten years; and, as will shortly appear, it is in design altogether unique.” The resultant article was published in August 1838, and the description was “rendered more perfect” by “beautiful woodcuts, in the superior style for which this magazine is famous.”

Loudon admired the distant views to the Welsh mountains, the Peckforton Hills, and Beeston Castle. The design of the rockwork, we are told, was “taken from a small model representing the mountain of Savoy, with the valley of Chamouni: it has been the work of many years to complete it, the difficulty being to make it stand against the weather”:

Rain washed away the soil, and frost swelled the stones: several times the main wall failed from the weight put upon it. The walls and the foundations are built of red sandstone of the country; and the other materials have been collected from various quarters, chiefly from Wales; but it is now so generally covered with creeping and alpine plants, that it all mingles together in one mass.

Although lushly planted, the “outline” was “carefully preserved”; and the part of the model that represents la Mer de Glace was “worked with gray limestone, quartz, and spar.”

It has no cells for plants; the spaces are filled up with broken fragments of white marble, to look like snow; and the spar is intended for the glacier. On the small scale of our engravings, and without the aid of color, it is altogether impossible to give an adequate idea of the singularity and beauty of this rocky boundary; and we may add that it is equally impossible to create anything like it by mere mechanical means.

By setting the garden in contrast to one produced by “mere mechanical means,” Loudon presumably set out to emphasize that a landscape so personal, and so dependent upon a willingness to experiment and take risks, could hardly have been produced through the more conventional method of employing an architect or a landscape gardener to ensure a degree of structural safety and soundness. Loudon, eager to praise Dame Eliza, then states firmly—and flatteringly: “There must be the eye of the artist presiding over every step; and the artist must not only have formed an idea of the previous effect of the whole in his own mind but must be capable of judging of every part of the work as it advances with reference to that whole”:

In the case of this rockwork, Lady Broughton was her own artist; and the work she has produced evinces the most exquisite taste for this description of scenery. It is true it must have occupied [a] great part of her time for six or eight years past; but the occupation must have been interesting, and the result, as it now stands, must give Her Ladyship the highest satisfaction.

Jane Loudon—who presumably accompanied her husband on his 1838 tour—was equally effusive when she described the Savoyard set piece in an 1842 issue of Ladies’ Magazine of Gardening as producing “a scenic illusion perfectly unique of its kind”:

[It]…is perhaps the most remarkable and best executed rock garden in existence. It is formed on a level surface, and consists of an imitation or miniature copy of the Swiss glaciers; with a valley between, into which the mountain scenery projects and retires, forming several beautiful and picturesque openings, which are diversified by scattered fragments of rock of various shapes and sizes, and by mountain trees and shrubs, and other plants.

The “open part” of the rockwork was planted with a collection of the “most beautiful Alpine plants, particularly those of low growth; each is placed in a little bed of suitable soil, the surface of which is covered by broken fragments of stone, clean-washed river gravel, the remains of decaying moss, etc., according as the object is to retain moisture around those plants which are liable to be injured by drought.” The heady climax of the scene of “wild irregularity” was the “part representing the Mer de Glace, where the imitation of the glaciers is so complete that a sensation of coolness is felt even in the midst of summer.”

Despite the eccentricity of Dame Eliza’s decision to embosom her flower garden in a crystalline landscape, her fascination with the glacier and its setting near Chamonix was not in itself surprising or unusual. It is possible that she visited the glacier during the short period of peace between Britain and France following the 1802 Treaty of Amiens or after the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, but in any case the pass through the Chamonix valley had become a popular route for northern European travelers since the late eighteenth century. Lady Broughton’s rockwork could be based on a close reading of Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, which supplies a vivid description of the Mer de Glace, which she had visited in 1817:

I descended upon the glacier. The surface is very uneven, rising like the waves of a troubled sea, descending low, and interspersed by rifts that sink deep. The field of ice is almost a league in width, but I spent nearly two hours crossing it. The opposite mountain is bare perpendicular rock. From the side where I now stood Montanvert was exactly opposite, at the distance of a league; and above it rose Mont Blanc, in awful majesty. I remained in a recess of rock, gazing at this wonderful and stupendous scene. The sea, or rather the vast river of ice, wound among its dependent mountains, whose aerial summits hung over its recesses. Their icy glittering peaks shone in the sunlight over the clouds. My heart, which was before sorrowful, now swelled with something like joy.

What impressed upon visitors to Hoole during Lady Broughton’s lifetime, and Jane Loudon in particular, was that her rockwork was such a daring enterprise carried out in a spirit of extreme experimentation—that it “required the eye of an artist, combined with great good taste, to arrange these materials so as to produce the desired effect; as a single false step would have made the whole pass from the sublime to the ridiculous.” Lady Broughton had presumably been emboldened by her own gardening experience; she was familiar with the challenge posed by major landscape operations, since she had witnessed as a child the dramatic ten-year transformation of her family’s park and gardens at Oulton under the direction of the landscape gardeners William Eames and John Webb.

If Dame Eliza spent almost four decades building and unbuilding her garden, her last will and testament suggests that she also gave due consideration to her own end and the fate of her garden after her death. One of her first wishes was that she should have a “proper but private” funeral, and should be “carried to the grave by my gardener [John Edwards] and his first laborers.” There were many special bequests; the most tantalizing of all is Dame Eliza’s bequest to her nephew Sir Philip de Malpas Grey-Egerton, 10th Baronet, of a “rosewood commode containing seven Alpine models.” Might one of these have been the “small model representing the mountain of Savoy, with the valley of Chamouni,” referred to by Loudon in 1838? Sir Philip was an eminent geologist and paleontologist whose interest in these subjects had been aroused while studying under Dean William Buckland at Oxford in the 1820s. Immediately following his graduation he embarked with his friend William Willoughby Cole, later 3rd Earl of Enniskillen, on a geological grand tour of the continent, and while traveling in Switzerland they met the Swiss paleontologist Louis Agassiz, who persuaded them both to focus on collecting fossil fishes.

One does not know whether Dame Eliza’s Alpine models still exist or what they looked like. They may have been something like the plaster models of megalithic subjects contained in Henry Browne’s 1826 cork model of Stonehenge. Models of the glaciers, however, are described, with some fascination, by various writers of the time. The well-known botanist Sir James Edward Smith, in his 1793 Sketch of a Tour on the Continent, describes one such model “in miniature” as an adumbration of his experience with these great works of nature on the spot:

At Servos, a village at the entrance of the valley of Chamouni, I called on Mr. Exchaquet, superintendent of the neighboring mines, in order to see his model of the glaciers and valley of Chamouni, and was extremely pleased to have such a comprehensive view in miniature of the noble scenes I was going to admire. This model is carved in wood and colored, the ice being well imitated by broken glass. Its scale is about a line to eighteen toises; that is, 15,552 times less than the vast original!

Wordsworth, too, proclaims his acquaintance with Alpine models; in the introduction to his 1810 Guide through the Lakes, he begins not with an account of lake scenery, not of the actual scenery at all, but with the report of a model—one that sounds rather more ambitious in scale and scope than Smith’s:

At Lucerne, in Switzerland, is shewn a model of the Alpine country which encompasses the Lake of the four Cantons. The Spectator ascends a little platform, and sees mountains, lakes, glaciers, rivers, woods, waterfalls, and valleys…It may be easily conceived that this exhibition affords an exquisite delight to the imagination, tempting in it to wander at will from valley to valley, from mountain to mountain, through the deepest recesses of the Alps. But it supplies also a more substantial pleasure: for the sublime and beautiful region, with all its hidden treasures, and their bearings and relations to each other, is thereby comprehended and understood at once.

Lady Broughton’s glacier garden is not explicitly classified as a miniature by her contemporaries, but this reconstruction, too, taking models of glaciers as its inspiration, can be viewed as a larger-scale model.

Excerpted from English Garden Eccentrics: Three Hundred Years of Extraordinary Groves, Burrowings, Mountains, and Menageries by Todd Longstaffe-Gowan, published by the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. Copyright © 2022 Todd Longstaffe-Gowan. Reprinted by permission of the Paul Mellon Centre.