Good Night, c. 1912. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. But, being in print, the magazine can only draw upon examples from the past that can appear on the page. Below we present night as seen from the history of moving images and sound.

Nocturnes

James Abbott McNeill Whistler first called his night paintings moonlights, an evocative term for the feeling he was trying to create, the muddy evening sinking into the Thames, his brush dappling the waves with light, looming buildings watching over the landscape in their sleep, the scene’s colors filtered through the black and blue of the sky, quiet absolute. Frederick Leyland, the art collector who would later commission Whistler to turn his dining room into the now famous Peacock Room, came up with the title Whistler’s nights would later bear. “I say I can’t thank you too much for the name ‘Nocturne’ as a title for my moonlights!” Whistler wrote his patron in 1872. “You have no idea what an irritation it proves to the critics and consequent pleasure to me—besides it is really so charming and does so poetically say all that I want to say and no more than I wish.”

That first painting, Nocturne: Blue and Silver—Chelsea, was finished in August 1871, and is now owned by the Tate. In 1877 art critic John Ruskin complained about Whistler’s Nocturne in Black and Gold, saying, “I have seen, and heard, much of cockney impudence before now; but never expected to hear a coxcomb ask two hundred guineas for flinging a pot of paint in the public’s face.”

The hatchet job led Whistler to sue Ruskin for libel, and during the court case (in which Whistler won a single farthing and Ruskin lost his reputation), the artist was asked to define nocturne. “By using the word nocturne,” Whistler explained,

I wished to indicate an artistic interest alone, divesting the picture of any outside anecdotal interest which might have been otherwise attached to it. A nocturne is an arrangement of line, form, and color first. The picture is throughout a problem that I attempt to solve. I make use of any means, any incident or object in nature, that will bring about this symmetrical result…Among my works are some night pieces, and I have chosen the word nocturne because it generalizes and simplifies the whole set of them; it is an accident that I happened upon terms used in music. Very often have I been misunderstood from this fact, it having been supposed that I intended some way or other to show a connection between the two arts, whereas I had no such intention.

Of course, nocturne is a word with outside anecdotal interest; as Whistler notes, it had existed for decades already as a term for music meant to evoke night in all its flavors, whether moody, ruminating, or muddled. An Irish composer, John Field, wrote the first nocturne in 1814—at least if we define a musical nocturne as a piece that sounds like night, instead of a song merely to be played in the dark. In eighteenth-century Italy, a notturno was to be played at night, not meant to be redolent of it.

Franz Liszt later wrote of the Field nocturnes in the 1850s:

A balmy freshness, a fragrant odor, is still wafted to us from them. Since Field, no one has been able to express himself in that language of the heart, which moves us as a tender, moist glance does; which cradles to repose, like the soft, equal rocking of a boat, or the swinging of a hammock, which is so gentle and easy, that we fancy we hear around us the low murmuring of dying kisses.

Yet Field has mostly faded from historical memory, replaced in nocturne lore with the pianist who perfected the form with his twenty-one iterations: Frédéric Chopin. Many reviews of the Polish French composer’s night music were rendered in verse, like this take by Canadian novelist Arthur Stringer, quoted in The Bookman in 1901:

Saddened and desolate, he sought the gleam

On that white summit where lone beauty dwelt.

He far from us some fragile marble found,

And in its snows the unreturning dream

He molded there, and we but see it melt

As Music into April showers of sound.

Many other musicians—and novelists and painters—have since borrowed the term for their own compositions, including Claude Debussy, Béla Bartók, Edvard Grieg, andBilly Joel.

Early film shot in the evening often feels like a sibling of Whistler’s nights, a blurred dream that, akin to a Chopin nocturne, looks more like night than the crisp cinematography of twenty-first-century movies. In 1905, Thomas Edison went to Coney Island with his camera to capture the lights on the water.

The Moon

There are many reasons to love the moon. Its soft glow illuminates the dark. It arrives each night, slightly changing its garb every day. It is our closest celestial acquaintance. It appears to every person on the planet, which means that each culture has its own interpretation of the moon’s existence and relevance: a symbol of life and fertility and change, a harbinger of monsters and strange behavior and romance. The poet John Squire seems to have found inspiration in this multiplicity of meanings when, in 1920, he wrote,

Unnumbered are those moons of memory

Stored in the backward chambers of my brain

The moon’s omnipresence combined with its remoteness make it an object of mystery and curiosity. Is there life on the moon? If there are Selenites, what are they like and how do they live? What secrets are hidden on its dark side? Noted astronomer William Herschel, best known for his discovery of the planet Uranus and the brother of the pioneering astronomer Caroline Herschel, wrote in 1780,

Perhaps—and not unlikely—the Moon is the planet and Earth the satellite! Are we not a larger moon to the Moon than she is to us?

Herschel also expressed a desire to live on the moon, saying that he would prefer it to Earth. Two hundred years later, Ernie of Sesame Street expressed a contrary opinion, singing,

I’d like to visit the moon, but I don’t think I’d like to live there.

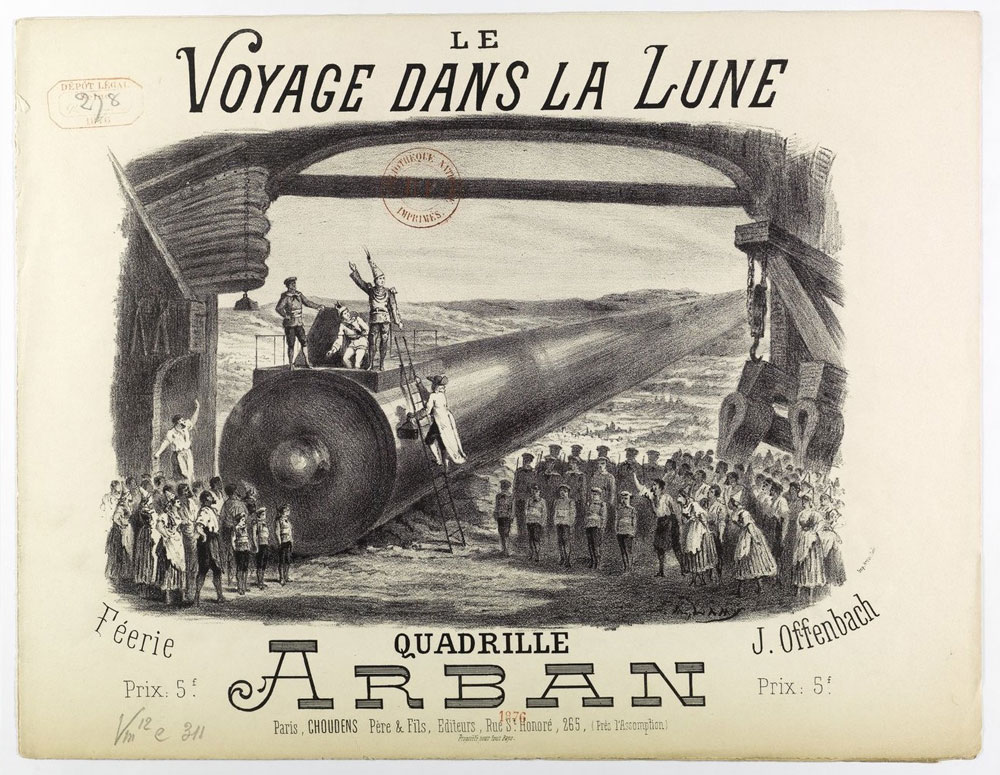

Jules Verne’s novel From the Earth to the Moon (1865) and its sequel Around the Moon (1870) imagine the production and eventual use of a giant projectile gun that sends three gun-enthusiast adventurers to the moon. These novels served as inspiration for other works of art, including the 1875 operetta Le Voyage dans la lune (A Trip to the Moon), with music by Jacques Offenbach, and George Méliès’ famous 1902 film of the same name.

One of the astronauts in Offenbach’s operetta falls in love with a Selenite, Fantasia, only to discover that love does not exist on the moon. A bite of an Earth apple infects Fantasia with love. Her fellow moon dwellers consider her defective and decide to sell her at market. When other women of the moon become infected with love, the furious king of the moon condemns the astronauts to five years in a purportedly inactive volcano. It erupts and throws the astronauts and their lunar girlfriends to safety. The Le Figaro review of Le Voyage dans la lune insisted that all the opera borrowed from Verne’s novel was the mode of transit—travel to moon by cannon—and praised the opera for its success as a satire of modern society. The cannon is clearly visible as a large set piece in scenes from the opera, which were reproduced and sold as stereographs, an early form of 3-D imagery.

In Méliès’ film, the astronauts meet and capture a Selenite, and then bring their captive back to Earth. The film’s most iconic moment—the lunar capsule landing in the moon’s eye—is perhaps one of the most famous images in film history. A Trip to the Moon became famous not only for its lunar subject matter but also for its technical accomplishments in a relatively new medium.

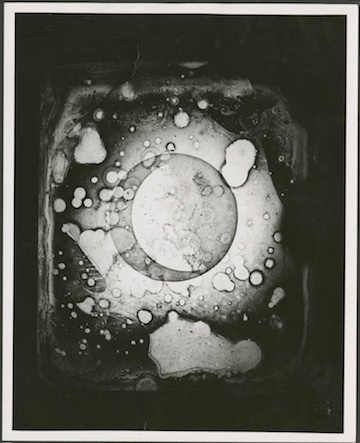

We have tried to capture the moon’s image since the earliest days of photography. The first known attempt to photograph the moon was undertaken by Louis Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype, in 1839. While Daguerre produced only an indistinct blur, New York University professor John William Draper’s attempt the following year was much more successful.

In 1878 the noted astronomer Maria Mitchell traveled to Denver to view and take notes on the solar eclipse, which occurs when the moon’s path crosses in front of the sun. She later wrote, “The moon, so white in the sky, becomes densely black when it is closely ranging with the sun, and it shows itself as a black notch on the burning disc when the eclipse begins.”

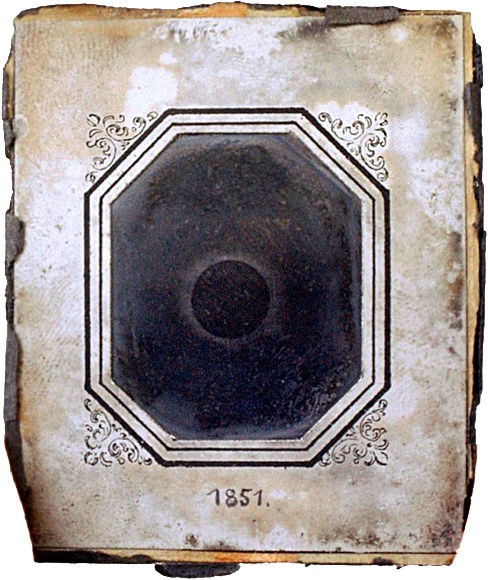

Images of eclipses are even more difficult to capture than images of the full moon, because there is much less light to interact with the photochemicals that made photography possible. One of the earliest total-eclipse photographs was taken in 1851 by Johann Julius Friedrich Berkowski in Königsberg.

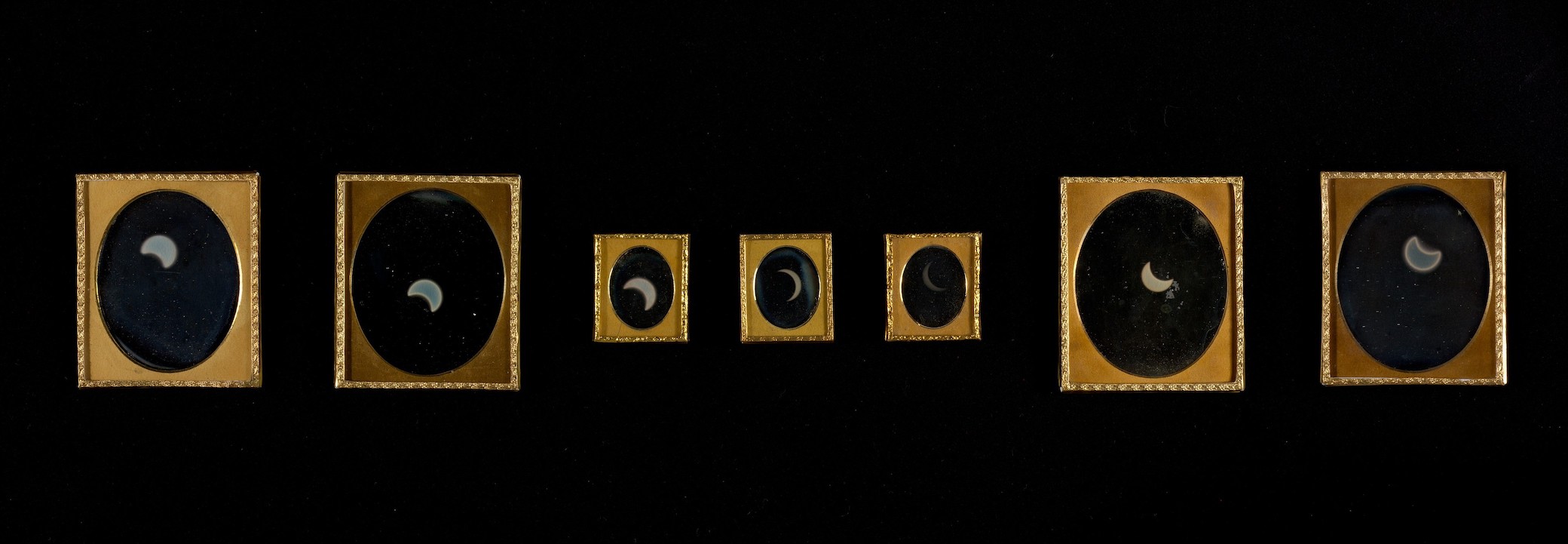

In 1854, William and Frederick Langenheim, daguerreotypists in Philadelphia, produced seven sequential daguerreotypes showing a solar eclipse from beginning to end. They made use of very small and sensitive cameras, producing tiny images, to make up for the low light.

Nightlife

What medium best represents the experience of attending parties, clubs, or the theater late at night?

In March 1894 a vaudeville dancer named Carmencita became the first woman filmed by an Edison motion-picture camera and possibly the first woman to appear on film at all. In the very short video, filmed at Edison’s studio, she dances, perhaps showing off one of the routines she regularly performed at Koster & Bial’s Music Hall in New York City from February 1890 until the fall of 1893.

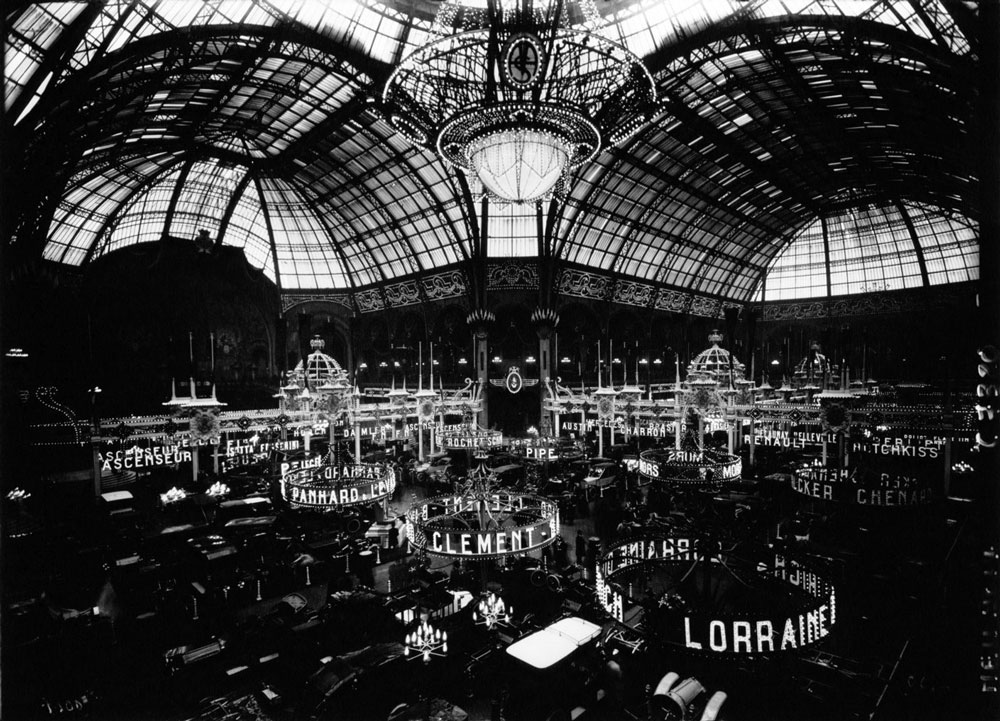

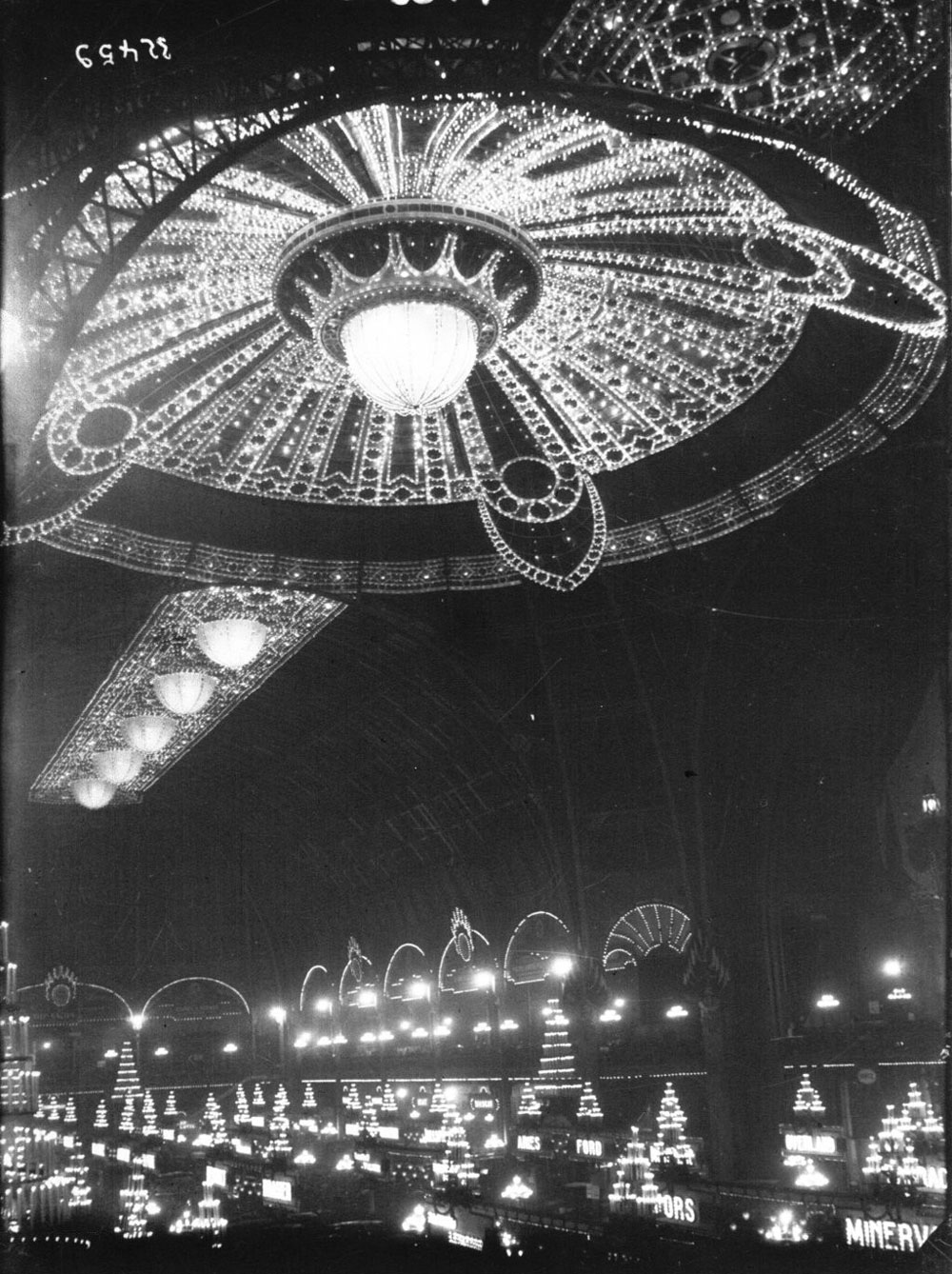

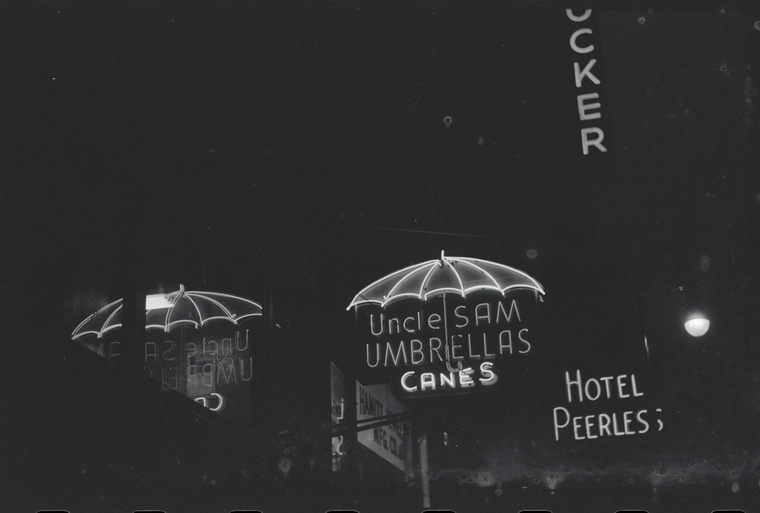

Neon lighting, invented by the “French Edison” and future Vichy collaborator Georges Claude, first appeared at the 1910 Salon de l’automobile in Paris. The lights, captured in black-and-white press photography at the time, also caught the eye of French photographer Léon Gimpel, whose prints made use of the recently invented color photography process autochrome lumière.

Neon lighting quickly became more complex and expressive, able to display whole scenes, and produced a clear aesthetic for nightlife in Paris and beyond. Neon signs for businesses, clearly announcing we are open after dark came to the United States via Claude’s company Claude Neon. In 1823 the company produced what may have been the first neon sign in the United States for Earl C. Anthony’s Packard car dealership in California.

Las Vegas, possibly the most neon-lit city in the world, even has a museum dedicated to the form, complete with a neon boneyard for discarded and broken signs.

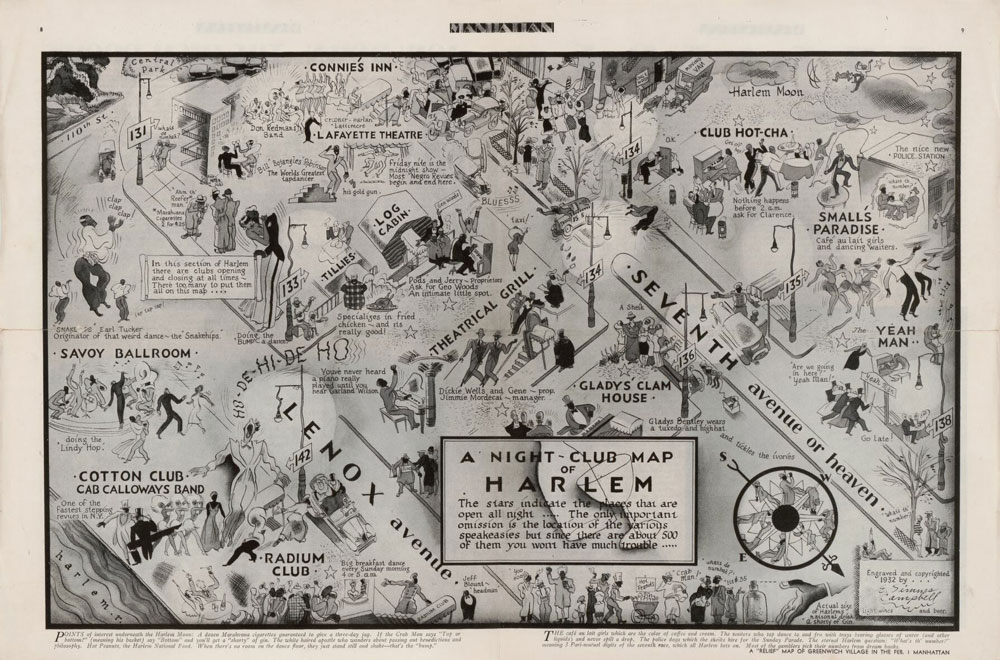

In 1933 the cartoonist E. Simms Campbell drew a map of nightclubs and nightlife in Harlem for the first issue of the short-lived magazine Manhattan—A Weekly for Wakeful New Yorkers. Campbell’s map combined famous locations known to white tourists and those known only to the neighborhood’s black locals, like Campbell himself. Stars indicated locations open all night, but the map omitted Harlem’s speakeasies with the explanation, “Since there are about five hundred of them you won’t have much trouble.”

Sleep

In the British Library’s audio database, there is a ten-minute recording of what the world sounds like when you are asleep (in Norfolk, England, in 2015). (Listen.)

“At five in the morning,” Pascal Wyse explains, “with a hangover starting to percolate, the ideal conditions are surely to just roll over, hit record, and go back to sleep—and that is pretty much what happened here. End of disclaimer.

Boats, whether out at sea or in harbor, have a particular vocabulary of sounds. On the water, they are masked by the white noise of the ocean, in which—as many sailors have reported—you can hear almost any sound imaginable. Moored up, where things are quieter, the water laps and slaps the hull while the wind plays aeolian harp on the mast. That rigging sound is often a chorus of tapping lines against masts, but this particular boat—a cruising yacht with a Bermuda rig, moored at Yarmouth after a day’s sailing—had an unusually musical voice, sounding clear notes as the wind passed through its structure. At sea this was a contented hum, but at night it felt much more ominous. The tones in this piece were recorded in one of the sleeping cabins in the stern, a little resonant box. Of course, there has been some processing—mainly to remove the snoring of sailors.

The recording sounds a bit like listening to a sound portrait of a dream, the content underwater and slightly hard to interpret while it keeps bumping up against you.

Most of the sounds we associate with sleep happen before we drift off (lullabies and white noise) or the sounds we leave behind for other people to try and edit out (snoring).

The first white-noise machine sold to the masses appeared in 1962, invented by Jim Buckwalter, a man who had become used to the purr of an air conditioner and was left awake in bereft silence when summer ended. A 1973 Los Angeles Times article on Buckwalter’s Marpac Sound Machine and its competitors, titled “Sometimes Noise Is Not Pollution but a Cocoon That Provides Solace,” compares the gadget’s sound to that of a “rolling surf.” Another article on the Marpac, published in 1982, featured the unforgivable headline here’s whooshing you a good night's sleep—by machine. The Marpac is still sold today, along with many other white-noise machines that purport to offer better and even more forgettable noise. Most are digital, offering a range of new and improved sounds—varying intensities of rain on the roof, clothes dryer—instead of the analog Marpac’s soft vacuum-inside-of-a-seashell whir.

But while audio related to sleep tends to trend soporific, film has often tried to capture the action of lying in bed—or at least the excitement happening in our heads when we go to sleep.

A Pathé film released in 1907 tried to show what might happen if a boy read too much Jules Verne before bed.

A film by Georges Méliès from a decade earlier features another form of nighttime drama.

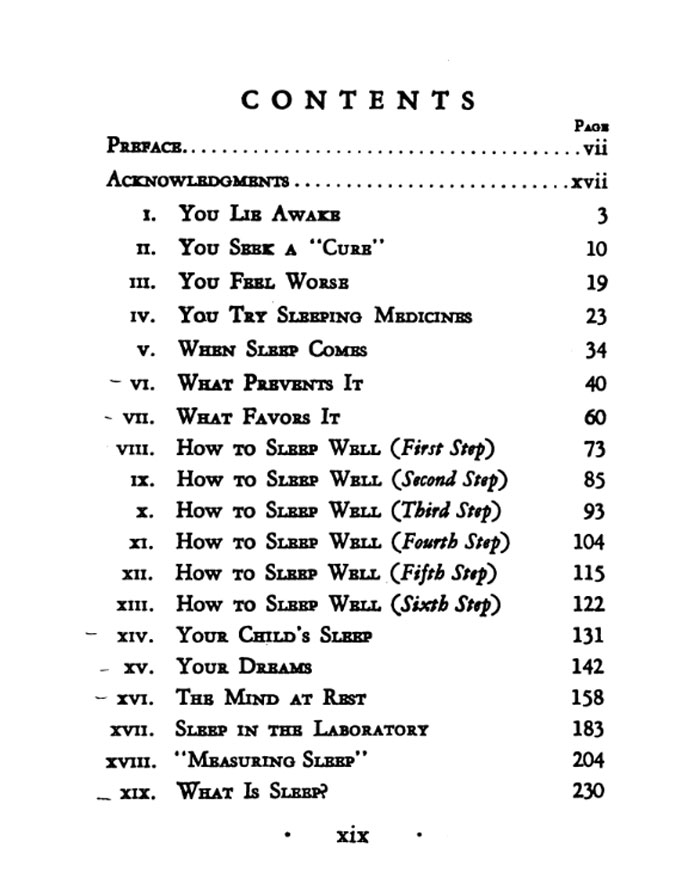

Apart from depictions of sleep is a long history of sleep self-help. One example: You Can Sleep Well; The ABC’s of Restful Sleep for the Average Person (1939) by Edmund Jacobson, MD, author of such other forgotten works as How to Relax and Have Your Baby.

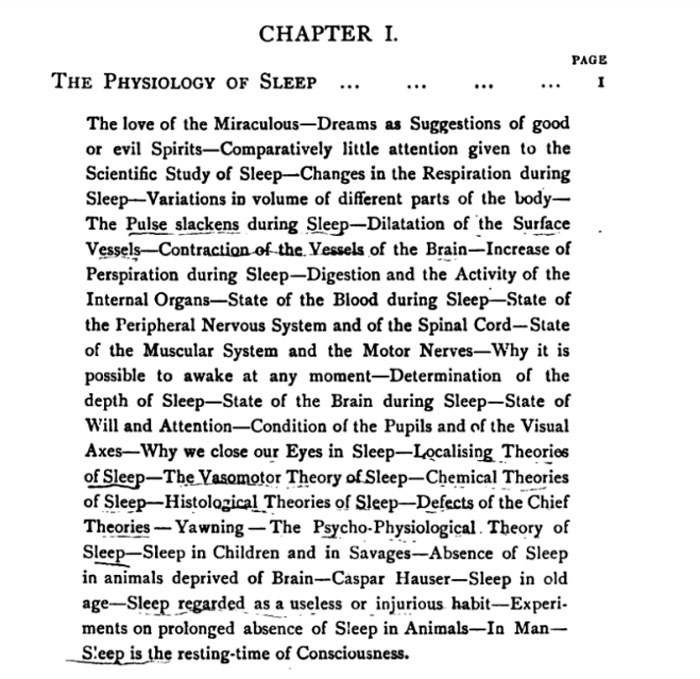

Historical books on sleep often have the added benefit of having aged into useful, if niche, versions of counting sheep, like these endless chapter descriptions in Sleep: Its Physiology, Pathology, Hygiene, and Psychology (1897) by Marie de Manacéïne in 1897.

A good, sleepy note to end on: listen to lullabies from India, recorded around 1910. The lyrics:

Baby mine, light of my eyes,

Here in thy cradle bright with flowers,

Through sunny hours I bring thee sleep,

I rock thee and sing thee to sleep,

On the wings of my melodies.