Portrait of Letitia Elizabeth Landon by Samuel Freeman, after J. Wright. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Between eight and nine o’clock on the morning of Monday, October 15, 1838, the body of a thirty-six-year-old Englishwoman, wearing a lightweight dressing gown, was found on the floor of a room in Cape Coast Castle, West Africa. She was the new wife of the British governor, George Maclean, and had arrived there from England only eight weeks previously.

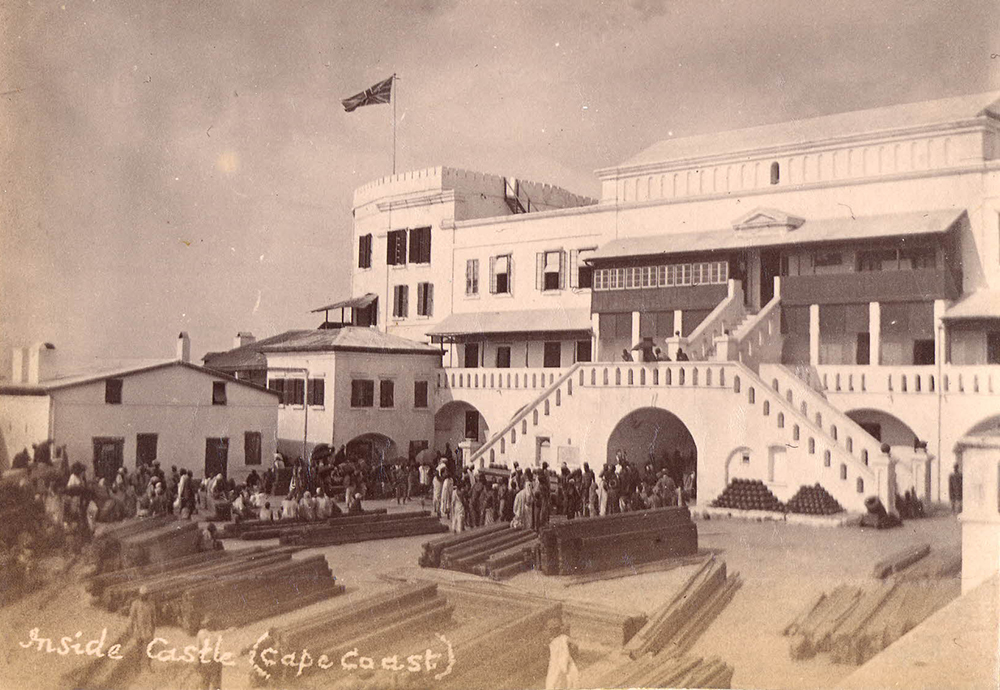

Cape Coast Castle was the largest trading fort on the western coast of Africa: a stark white complex bristling with cannon, perched on the edge of the Atlantic Ocean in what is now Ghana. During the eighteenth century, it had been the “grand emporium” of the British slave trade. Countless captives had been held in its underground dungeons before being shipped to the Americas, while slave dealers did business in its precincts. Following the Abolition Act of 1807, the castle had remained under British command, its dungeons repurposed for housing local “prisoners.”

A soldier in a sentry box stood at the entrance to the governor’s quarters, which were decorated in the European style: prints on the walls, a shining mahogany dining table, impressive table silver. The room in which the body was found, painted a deep blue, featured a toilet table and the deceased’s own portable desk, one of those small wooden boxes, typical of the period, that opened to form a sloping writing surface.

Deaths from disease among Europeans in what was then known as the “white man’s grave” were not uncommon. Indeed, the fatality rate was so great that the local Methodist missionary was having difficulty recruiting volunteers. But this death was different. In the woman’s hand was a small empty bottle. Her eyes were open and abnormally dilated.

The last person to see the governor’s wife alive was her maid, Emily Bailey, who had traveled out with her from England. She later testified that she had found Mrs. Maclean “well” when she went in to see her earlier that morning. On her return half an hour later, however, Emily Bailey had had difficulty opening the door. It had been blocked by her mistress’s body.

Soon after Mrs. Bailey raised the alarm, the castle surgeon arrived. He attempted to revive the patient, but in vain. Garbled news soon spread to the nearby hills. Brodie Cruickshank, a young Scottish merchants’ agent, arrived at the fort within the hour, mistakenly supposing that it was the governor himself who had perished. In his memoir Eighteen Years on the Gold Coast of Africa, he later recalled his shock on entering the room where Mrs. Maclean’s body had been laid out on a bed.

He had dined with the Macleans only the evening before, when she had appeared to be in “perfect health.” The governor himself was in the room. He had slid down into a chair and was silently staring into space, his face “crushed.”

Later that very day, an inquest was held at the castle, the jury hastily convened from among the local merchant community. No autopsy was performed, but the empty bottle was produced in evidence and its label carefully transcribed: “Acid Hydrocianicum Delatum, Pharm. Lond. 1836, Medium Dose Five Minims, being about one-third the strength of that in former use, prepared by Scheele’s proof.” The deceased was said to have been in the habit of using the contents, prussic acid in everyday parlance, for medicinal reasons, and to have taken too much by mistake. A verdict of accidental death was recorded. After the inquest, the corpse was hastily interred under the parade ground. During the burial, a tropical shower burst from the sky in such torrents that a tarpaulin had to be erected over the gravediggers. By the time the final paving stone was replaced it had grown dark. The workmen finished the job by torchlight.

West Africa was so remote from England that it was not until the morning of January 1, 1839, that a discreet death notice appeared in The Times:

At Cape Coast Castle, Africa, on Monday, the 15th of October last, suddenly, Mrs. L.E. Maclean, wife of George Maclean Esq., Governor of Cape Coast Castle.

But after the evening Courier revealed the woman’s maiden name later that day, the story became headline news. She was one of the most famous writers in England: Letitia Elizabeth Landon, better known by her initials, “L.E.L.”

Although she remains little heard of today outside specialist circles, L.E.L. was a “legendary figure” in her own time. According to a critic writing in 1841, her name was “so identified with the literature of the day, that not to know anything of it is scarcely possible.” Elizabeth Barrett (who later added Browning to her name following her marriage) believed her unrivaled among women poets for her “raw bare powers.”

In America, Edgar Allan Poe thought her “genius” so self-evident that it was “almost unnecessary to speak” of it. In Europe, she was admired by Goethe’s family, Heinrich Heine, and the influential Parisian Revue des deux mondes. Closer to home, her poetry was devoured by the young Brontës in provincial Yorkshire.

L.E.L. was, however, the voice of a lost literary generation. Her career, which spanned the 1820s and 1830s, coincided exactly with the “strange pause,” as the historian G.M. Young called it, between the Romantics and the Victorians. Modern scholars are still unsure exactly what happened during this troublesome transition phase between the deaths of Keats, Shelley, and Byron and the rise of Dickens. Referred to as “an embarrassment to the historian of English literature” and an “indeterminate borderland,” it resists periodization, and has never been dignified with a name. However, it should probably be called the “post-Byronic” era, since the fallout from Byron’s celebrity cult had such a profound impact on the writing of the day. Following his death in 1824, every hack wanted his—or her—own cult of personality. Yet the labile, often ironized voices writers created in response remain hard to interpret, their tone difficult for the modern reader to pin down. None is harder to read than that of the inscrutable L.E.L.

No one knew who she was when she first began to publish under her mysterious initials in the early 1820s. But in 1824 she emerged in public as the star author of a new best seller, The Improvisatrice. A skillful improviser of her own image, she soon became a celebrity, her portrait exhibited at the Royal Academy, her presence a fixture on the London social scene.

If she was the female Byron, “female” was the operative word. She was the “poetess” par excellence in a period in which, unusually in literary history, women dominated the genre. The eighteenth-century cult of sensibility, regarded by some modern cultural historians as the fons et origo of English Romanticism, had already produced some notable female poets, including Charlotte Smith and Mary Robinson, Letitia Landon’s literary foremothers. Following the untimely deaths of Keats, Shelley, and Byron, the “poetess” became culturally supreme. Not just in England but in France, Germany, Russia, and America, a new generation of women Romantics staked their careers on the supposition that their gender made them more sensitive and intuitive than men, and thus more poetical.

All the poetesses made capital out of the emotions, but Landon’s work struck its own peculiar chord. Her main English rival, Felicia Hemans, focused on the “domestic affections” and the moral value of altruism and empathy. But Letitia Landon’s favorite topic was thwarted romantic love. “I have sung passionate songs of beating hearts,” she wrote, summing up her feminine sensibility in the slogan “the fallen leaf, the faded flower, the broken heart, and the early grave.” In the view of Germaine Greer, writing in 1995, “No female poet before L.E.L. had ever written of women’s passion as she did. It was not like the love plaints of men, but the fierce, impotent, inward-turning tumult of a woman’s heart, the agony of a creature unable to speak or act, forced to wreak her vengeance on herself.” The passion in the work was always unrequited, always doomed, and invariably expressed in the first person. Whether the “I” of the poetry reflected Letitia Landon’s own true feelings remains to this day the ultimate crux of her legacy.

Later nineteenth-century women poets, such as Emily Dickinson, Emily Brontë, and Christina Rossetti, dressed like nuns and shunned society. But L.E.L. danced until the early hours and favored risqué décolletages in pink satin, scarlet cashmere, or black velvet. Contemporaries were startled by the contrast between the emotional extremism of her poetry and her society persona as a sardonic, glittering wit, a Dorothy Parker avant la lettre.

Behind the scenes she was an indefatigable worker, preternaturally productive in her bid to fill the public’s emotional void with her literary lamentations. Her oeuvre was so vast that it is yet to be fully cataloged. By the time she died at thirty-six, she had published six stand-alone poetry collections, three novels, and a book of short stories, plus at least ten further poetry collections in the then fashionable format of the “annual.” That, however, made up only a portion of an output that also included reams of occasional verses, prose fictions, and critical writings, plus an unknown number of unsigned reviews. A tragedy and a further novel were published posthumously.

No writer of Letitia Landon’s generation achieved wider currency in terms of sheer word count or name recognition. Given her lifetime fame, her subsequent disappearance from standard literary histories, even if only as a name, remains a conundrum. But that is not the only puzzle surrounding her. From the moment her death was announced in early 1839, it was clouded by an aura of mystery and mistrust, which grew and mutated as the story spread.

Even before her death, rumor had replicated around L.E.L. like a virus. Before she married George Maclean, she had spent most of her career living in a rented room above a girls’ school. But the respectability of her spinster lodgings had not prevented her romantic poetry from provoking a welter of salacious speculation about her private life. Aspersions were cast on her virtue, and several men were named as her supposed lovers.

Writing about passion in a female voice was a risky business for any nineteenth-century woman, as Charlotte Brontë later discovered when she published Jane Eyre and was suspected by the London literati of being the mistress of Thackeray, whom she had never met. In her late poem “Gossipping” [sic], L.E.L. hit back at the rumormongers:

These are the spiders of society;

They weave their petty webs of lies and sneers,

And lie themselves in ambush for the spoil.

Her death gave the spiders something new to spin…

Excerpted from L.E.L.: The Lost Life and Scandalous Death of Letitia Elizabeth Landon, the Celebrated “Female Byron” by Lucasta Miller. Copyright © 2019 Lucasta Miller. Excerpted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved. No part of this excerpt may be reproduced or reprinted without permission in writing from the publisher.