A Noblewoman Seated on the Ground Reading, by the Bute Master, c. 1285. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Lapham’s Quarterly published dozens of original essays in 2019, covering everything from medieval vegetable lambs to modern resurrections of literary reputations, recalcitrant scriveners and reparations, presidential campaigns and spiritualists to the stars. Here are just a few of our favorites.

Kirk Savage, “A Personal Act of Reparation”

One of the most difficult legal hurdles for the reparations movement is simply the passage of time between then and now. The perpetrators of the crime of slavery all died long ago. Proving in court that their past actions are even partially to blame for social inequities and disparities in the present is extraordinarily difficult. In Fitzgerald v. Allman the problem was the opposite. The perpetrators were everywhere, and their victims still alive and in the neighborhood. The structural disparities of slavery carried over directly into the postwar period and tainted politics, economics, and justice. Reparations of the kind Asa enacted, if expanded to a regional or national scale, would require massive transfers of wealth from whites to blacks. But even more fundamentally, this process of economic redistribution would require a revaluation of moral goods. No longer could white society maintain that its system of slavery had given moral and spiritual benefits to its victims that somehow balanced the labor and rights they had been forced to give away. Reparations required an honest accounting, one that did not spare the lies whites made up in order to hold on to their moral and fiscal balance sheets.

Emily Harnett, “William James and the Spiritualist’s Phone”

The dead spoke through Leonora Piper, and the living answered through her hand. Shouted, really, because the connection between her hand and Eternity was often spotty. Calling on the dead required this kind of stagecraft in the waning days of the Spiritualist movement, when every quack with a set of candles claimed knowledge of the occult. Leonora would first enter into a trance, goosefleshed and murmuring. The sitters would take her hand. They would then scream questions at her open palm, as though it were a murder suspect, or a bad dog, or the receiver of an old-timey telephone. In fact Leonora called her hand “my spiritual telephone.” Perhaps she knew, psychically, that her séances would one day resemble something far more terrifying: bad improv comedy.

Patricia A. Matthew, “Look Before You Leap”

If the duchess’ attendant is looking off in the distance, Dido Elizabeth Belle is staring right at the viewer. It seems as if something or someone has amused her. And yet the artist (originally thought to be Zoffany) connects her to a world different than the one she was raised in, one that her cousin safely enjoys. While it’s true that Dido, the daughter of Royal Navy officer John Lindsay Murray and the enslaved Maria Belle, is standing next to her white cousin, looking at the viewer, she remains tied to the legacy of her mother’s position. She is wearing a turban with a feather and carrying a basket of fruit, a reminder that, although she has been raised in Britain as an heiress and a gentlewoman, she remains connected to labor. Her cousin, with flowers in her hair, is simply holding a book, a sign of leisure and not industry in the eighteenth century.

Adam Morris, “Mankind, Unite!”

When muckraker and novelist Upton Sinclair decided to make a third run for the California governor’s mansion in the election of 1934, he released an innovative piece of campaign literature to launch his bid. Titled I, Governor of California—And How I Ended Poverty, the novella-length tract contained an imaginative text titled “The People’s History of California.” Written in 1933 at the nadir of the Great Depression and narrated from an imagined 1938, this “history” described the momentous events that transpired in the years between, a period that coincided with a Sinclair administration in California. By today’s standards, publishing fictive future history might be deemed a catastrophically self-indulgent way to begin a campaign. But readers in the 1930s recognized that Sinclair was resuming the reasonably esteemed late Victorian practice of using utopian and dystopian fiction to animate a political movement.

Olivia Rutigliano, “Fire!”

The negotiation of how to present fire-safety information to the public reveals an interesting development in the theater’s representation of itself within the culture of the city. Actors breaking character onstage and attempting to direct crowds, as well as actors noticing fire but nervously carrying on with their scenes anyway, expose how theater space was almost lawless and ungovernable in its commitment to entertainment and artifice. The escapism of the institution was so important to its integrity that theater managers, rather than give audiences important emergency information, insisted that such real-life disasters would never happen in a particular venue—in effect they were relying dangerously on an additional fiction to preserve the enjoyable environment of theatrical fiction. These directions acknowledge that not only were theaters potentially dangerous but also that audiences bore responsibilities as citizens inside that space—the theater space had become simultaneously a practical, civic institution and a place for escapist pastimes.

Pablo Maurette, “The Living Envelope”

There is something about the excoriation of a living person that has haunted and continues to haunt our sensibility like perhaps no other form of aggression. It is the pain we assume it entails, of course. It is the horror of its imagined duration. It also may be picturing the victim conscious throughout the ordeal. But it is more than any of those factors. It is the sense that the skin is the one border that cannot and must not be crossed, the one garment that cannot be removed. The skin, that final frontier between the internal body and the outside world, at once connects us to the exterior and protects us from it. More than mutilation, more than any other form of physical violence and humiliation, the skin’s removal from a living person is the ultimate violation of a sacred space where our identity, our biological integrity, and our very personhood is shaped. In the early modern period physicians began to dissect and flay human bodies for the first time since antiquity, abandoning deeply rooted notions of the corpse as a hallowed entity. The way we think about skin—its importance and the horror of its removal—stems to a large extent from the innovative work of the pioneers of modern anatomy.

Benjamin Aldes Wurgaft, “Animal, Vegetable, or Both?”

According to one medieval story, a soft white fleece grows from a green stalk. The plant’s substance yields muscle and blood the way other plants bear fruit. A newborn lamb appears atop the plant. As it matures, the stalk bends toward the ground and the lamb takes its first tentative steps, still attached to the stalk and linked to roots in the ground. Soon it begins to munch the grass, suggesting a cycle of life that runs from plant to animal and back again, all on the same patch of soil. The Vegetable Lamb of Tartary, also called the Scythian Lamb or borometz, was a widespread tale conveying what wonders lay to the East, beyond the confines of late medieval and early modern Europe—the kind of chimeric wonders that seemed to recede as the searching traveler approached. Call the Vegetable Lamb a myth, yet it is still an effort to ask how the world makes sense by contemplating a creation that challenges the way we order things. It allows for a liminal space between the categories of fauna and flora. As late as the 1890s, scholars were still commenting on the Lamb, and while these moderns looked on the legend with skepticism and wrote to debunk it, they were writing about it nonetheless. Generations after scholars stopped writing about the Lamb, it still stands, bleating, for how past generations sutured together the disparate, unfamiliar parts of nature in search of a coherent whole.

Danielle A. Jackson, “A Quest That’s Just Begun”

Collins was constructing a lineage, an imagined community shaped out of recognition, not for representation’s sake, but for company—as a talisman to ward off, or at least soften, the loneliness and isolation of breaking through. Though buried and underdiscussed, these ancestral lines, scenes, paths, and archives of relation have always existed. Perhaps, to survive, we forget how much has been submerged, uprooted, stricken from the record. We forget how populous with precedents and peers every endeavor must be to bloom.

Melissa Mesku, “Restoring the Ship of Theseus”

If Washington’s ax were to have its handle and blade replaced, would it still be the same ax? The same has been asked of a motley assortment of items around the world. In Hungary, for example, there is a similar fable involving the statesman Kossuth Lajos’ knife, while in France it’s called Jeannot’s knife. This knife, that knife, Washington’s ax—there’s even a “Lincoln’s ax.” We don’t know where these stories originated. They likely arose spontaneously and had nothing to do with the ancient Greeks and their philosophical conundrums. The only thing uniting these bits of folklore is that the same question was asked: Does a thing remain the same after all its parts are replaced? In the millennia since the ship of Theseus set sail, some notions that bear its name have less in common with the original than do the fables of random axes and knives, while other frames for this same question threaten to replace the original entirely.

Daniel Tovrov, “I Would Prefer Not To, Your Honor”

Bartleby is so inscrutable as to appear unthinking, even inhuman. This uncanniness is one reason why Melville’s odd story is cherished like few others in American literature. Generation upon generation of literary scholars and armchair intellectuals have foisted their interpretations—Marxist and Protestant, biographical and bibliographical, abolitionist and transcendental—upon sad Bartleby, he who is unable to confirm or deny whatever theory is applied. Judges, scholars of a specific literature, are no different in bending Bartleby to their will. For such agents of the judicial system—which relies on faith in the comprehensiveness, consistency, and efficacy of its particular set of rules—interpretation tends to focus on the scrivener’s resolute noncompliance. If Bartleby as a literary character is an open sign who gestures toward an unknown, Bartleby in the legal sense signifies what the law abhors: an action that cannot be compelled, a docket that cannot be resolved, a citizen who cannot be summoned in full—and thus can only be held in contempt.

Also in 2019 the Quarterly excerpted new histories of debutantes, gold rush daguerreotypists, expeditions to the north, medieval scrolls, Mesopotamian recipes, and Victorian children’s books. Here are a handful of others from books published this year.

Johanna Hanink, “A Possession for All Time,” from the introduction to How to Think About War: An Ancient Guide to Foreign Policy by Thucydides (Princeton University Press)

On August 11, 1777, John Adams, then a delegate to the Second Continental Congress in session in Philadelphia, wrote a letter to his ten-year-old son, John Quincy. In light of the ongoing War of Independence and with a mind to other wars and “Councils and Negotiations” that the future might hold for the boy, Adams urged him “to turn your Thoughts early to such Studies, as will afford you the most solid Instruction and Improvement for the Part which may be allotted you to act on the Stage of Life.” He gave one recommendation in particular: “There is no History, perhaps, better adapted to this usefull Purpose than that of Thucidides.” For Adams, Thucydides’ History of the Peloponnesian War contained within it insight of every possible “usefull” sort: “You will find it full of Instruction to the Orator, the Statesman, the General, as well as to the Historian and the Philosopher.” For centuries, Thucydides has been made to wear each of those very hats. Politicians and military personnel, historians, political scientists, and classicists have all laid claim, often in radically different ways, to his work and wisdom.

Sarah A. Seo, “The Need for Speed Limits,” from Policing the Open Road: How Cars Transformed American Freedom (Harvard University Press)

Local governments responded swiftly by enacting laws and more laws. In addition to speed limits and license requirements, new regulations mandated safety equipment, like nonglaring headlights, rearview mirrors, and, in Massachusetts, at least two brakes for cars with horsepower greater than ten. They also prohibited motorized vehicles on certain roads; determined who among cars, horses, carriages, and pedestrians had the right of way; and specified how fast a car could overtake horse-drawn coaches and trolleys. According to one legal eagle, San Francisco even regulated “the angle at which motorists should make turns from one street into another.” In a short time, the number of regulations multiplied exponentially. In 1905, three years before the introduction of Ford’s Model T, a treatise on municipal corporations mentioned the automobile in just one line: “Bicycles, tricycles, and automobiles are ordinarily considered vehicles and entitled to the use of that part of the street or highway set aside for them.” Tellingly, another treatise published just seven years later, in 1912, devoted two entire sections to the regulation of “the running of automobiles.” An observer in 1920 noted that the “enormously increased traffic has given birth to laws that are now almost countless,” to the point that they could “fill a separate manual to overflowing and their number is added to at each session of the legislatures.”

Leo Damrosch, “James Boswell Finds His Voice,” from The Club: Johnson, Boswell, and the Friends Who Shaped an Age (Yale University Press)

What Boswell wanted above all was to establish a consistent character, reliably the same at all times, and to be admired for his stability. “I have discovered,” he wrote hopefully soon after arriving in London, “that we may have in some degree whatever character we choose.” But as he had to admit a few years later, “I am truly a composition of many opposite qualities.” Pottle calls him “an unfinished soul.”

One problem was that Boswell could never resist being the life of the party, inviting companions to laugh at him as much as with him. “I was, in short, a character very different from what God intended me and I myself chose.” If only he could be certain what God meant him to be, and then be it!

Christopher E. Forth, “Fat Tyrants,” from Fat: A Cultural History of the Stuff of Life (Reaktion Books)

When Socrates announced that he wanted to take up dancing, all his friends at the drinking party broke out with laughter. What was so funny about this declaration? Socrates wondered. Was it because dancing might be good for his health and well-being, or that it would exercise all of his muscles and render his proportions more balanced and beautiful? “Or is this why you’re laughing,” Socrates asked, indicating his round belly, “because my stomach is larger than it should be and I want to reduce it to more normal size?” If these questions were largely rhetorical, this is not the first time Socrates’ body was discussed in ancient texts.

Kerri K. Greenidge, “Holding a Mirror Up to Nature” from Black Radical: The Life and Times of William Monroe Trotter (Liveright)

Thus, from the beginning, Trotter’s new weekly, the Guardian, showed its audience the real-life consequences, without pretense, of white supremacy, federal apathy, and conservative uplift. Unconcerned with the poetry, short stories, and serialized fiction that made the Colored American so unique, the Guardian dealt with what its editors called “the truth.” Like the muckrakers Ida Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker, who were concerned with using the press to expose institutional abuses of the era, Trotter and Forbes wanted to “hold a mirror up to nature.” They aimed to do this by agitating for racial revolution and exposing the damage wrought by both accommodation to white supremacy and Republican neglect of civil rights…For Trotter, the Guardian was an “arsenal,” which meant that he and Forbes stood on the “firing line” in a war for civil rights in which conservative Americans, black and white, refused to engage. “I can now feel,” he concluded, “that I am doing my duty and trying to show the light to those in darkness and to keep them from at least being duped into helping in their own enslavement.”

Pekka Hämäläinen, “The Pipe Holds Them All Together,” from Lakota America: A New History of Indigenous Power (Yale University Press)

First there was but a speck. From out of the immense flat a figure emerged slowly, as if floating, gleaming white in hot air. The two men on the hill saw that it was a woman and that she was wakȟáŋ, holy, so they waited. As the woman grew larger, they saw that she was carrying a bundle and that her hair covered her body like a robe. One of the men lowered his eyes, but the other kept staring at her. She saw that he desired her and asked him to come near. A cloud concealed them. When it dissolved, the woman stood alone, a pile of bones and snakes at her feet. She turned to the other man and told him to go back to his village and have his people prepare a lodge for her. When she arrived four days later, the village was ready.

Sarah Schrank, “Land of the Free,” from Free and Natural: Nudity and the American Cult of the Body (University of Pennsylvania Press)

American nudism, and the free and natural lifestyle of which it was a part, grew out of Lebensreform (or “life reform”), a mid-nineteenth-century German health movement that encouraged urban dwellers to address the ills of industrial society by living more naturally. Nudist philosophy, which was referred to by British practitioners as naturism, and by Germans as Nacktkultur, included vegetarianism; exposure to fresh air, water, and sunlight; abstinence from tobacco and alcohol; and back-to-nature activities like gardening, hiking, and camping. To explain social nudism to American audiences and study the therapeutic possibilities of group nudity, Howard C. Warren, a professor of psychology at Princeton, published a widely circulated essay in 1933 in which he described his stay at the German nudist camp Klingberg, near Hamburg. Klingberg was owned by Paul Zimmerman, who had purchased the property in 1902, in social nudism’s very early years, and had raised his family according to the principles and protocols of the emergent body culture. Warren concluded that nudists were not “radicals, social rebels, or faddists,” nor would he characterize them as “perverts or neurotics.” Instead, everyone was relaxed, “natural, and unconstrained.”

Ted Gioia, “J.S. Bach the Rebel,” from Music: A Subversive History (Basic Books)

I’ve talked to people who feel they know Bach very well, but they aren’t aware of the time he was imprisoned for a month. They never learned about Bach pulling a knife on a fellow musician during a street fight. They never heard about his drinking exploits—on one two-week trip he billed the church eighteen groschen for beer, enough to purchase eight gallons of it at retail prices—or that his contract with the Duke of Saxony included a provision for tax-free beer from the castle brewery; or that he was accused of consorting with an unknown, unmarried woman in the organ loft; or had a reputation for ignoring assigned duties without explanation or apology. They don’t know about Bach’s sex life: at best a matter of speculation, but what should we conclude from his twenty known children, more than any significant composer in history (a procreative career that has led some to joke with a knowing wink that “Bach’s organ had no stops”), or his second marriage to twenty-year-old singer Anna Magdalena Wilcke, when he was in his late thirties? They don’t know about the constant disciplinary problems Bach caused, or his insolence to students, or the many other ways he found to flout authority. This is the Bach branded as “incorrigible” by the councilors in Leipzig, who grimly documented offense after offense committed by their stubborn and irascible employee.

Anthony McCann, “Sovereign Lands,” from Shadowlands: Fear and Freedom at the Oregon Standoff (Bloomsbury)

The history of Oregon’s Harney Basin after white conquest, like that of much of the region, has been a history of the collisions of American dreams with the rocky reality of the arid West. That history can be epic and it can be ugly. Before 2016, when Ammon Bundy added his name to the rolls, no single Anglo name had stood out in the tale of this remote land quite like the name Pete French. In 1868, when he came over the gap from the arid Catlow Valley and into the watered valley of the Blitzen, French had also liked very much what he saw.

Holly Jackson, “What’s Next?,” from American Radicals: How Nineteenth-Century Protest Shaped the Nation (Crown)

While orators in other cities and towns sang the praises of the American founders, Owen focused instead on the limits of their achievement. They had been forced to settle for mere “political independence,” he claimed, hemmed in by the old-world prejudices that still dominated their era. But they could glimpse “a stronger and clearer light at the distance,” he explained, and the founders trusted that their descendants would pick up where they left off, completing the transformation they had only begun. Indeed, a second revolution was required, a new battle for freedom “superior in benefit and importance to the first revolution.” He asked the crowd, “Are you prepared to imitate the example of your ancestors? Are you willing to run the risks they encountered? Are you ready, like them, to meet the prejudices of past times, and determined to overcome them at all hazards, for the benefit of your country and for the emancipation of the human race?” To launch this revolution, Owen presented his Declaration of Mental Independence to supplant the founding document adopted fifty years before that day. Its object was to slay a “Hydra of Evils” enslaving mankind the world over: specifically, the “threefold horrid monster” of private property, religion, and marriage.

Camilla Townsend, “Inventing a God,” from Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs (Oxford University Press)

It would become an accepted fact that the indigenous people of Mexico believed Hernando Cortés to be a god, arriving in their land in the year 1519 to satisfy an ancient prophecy. It was understood that Moctezuma (also known as Montezuma II), at heart a coward, trembled in his sandals and quickly despaired of victory. He immediately asked to turn his kingdom over to the divine newcomers, and naturally, the Spaniards happily acquiesced. Eventually, this story was repeated so many times, in so many reputable sources, that the whole world came to believe it.

Jack Hartnell, “Eventually, Everyone Needs to Urinate,” from Medieval Bodies: Life and Death in the Middle Ages (W.W. Norton)

One aspect of the body united all people, female and male alike: eventually, everyone needs to urinate. Within the logic of medieval humoral medicine, however, everything that was expelled from the body—sweat, vomit, saliva, feces—could be pored over for its quality and quantity by a knowledgeable healer for signs of underlying internal imbalance, and urine was no exception.

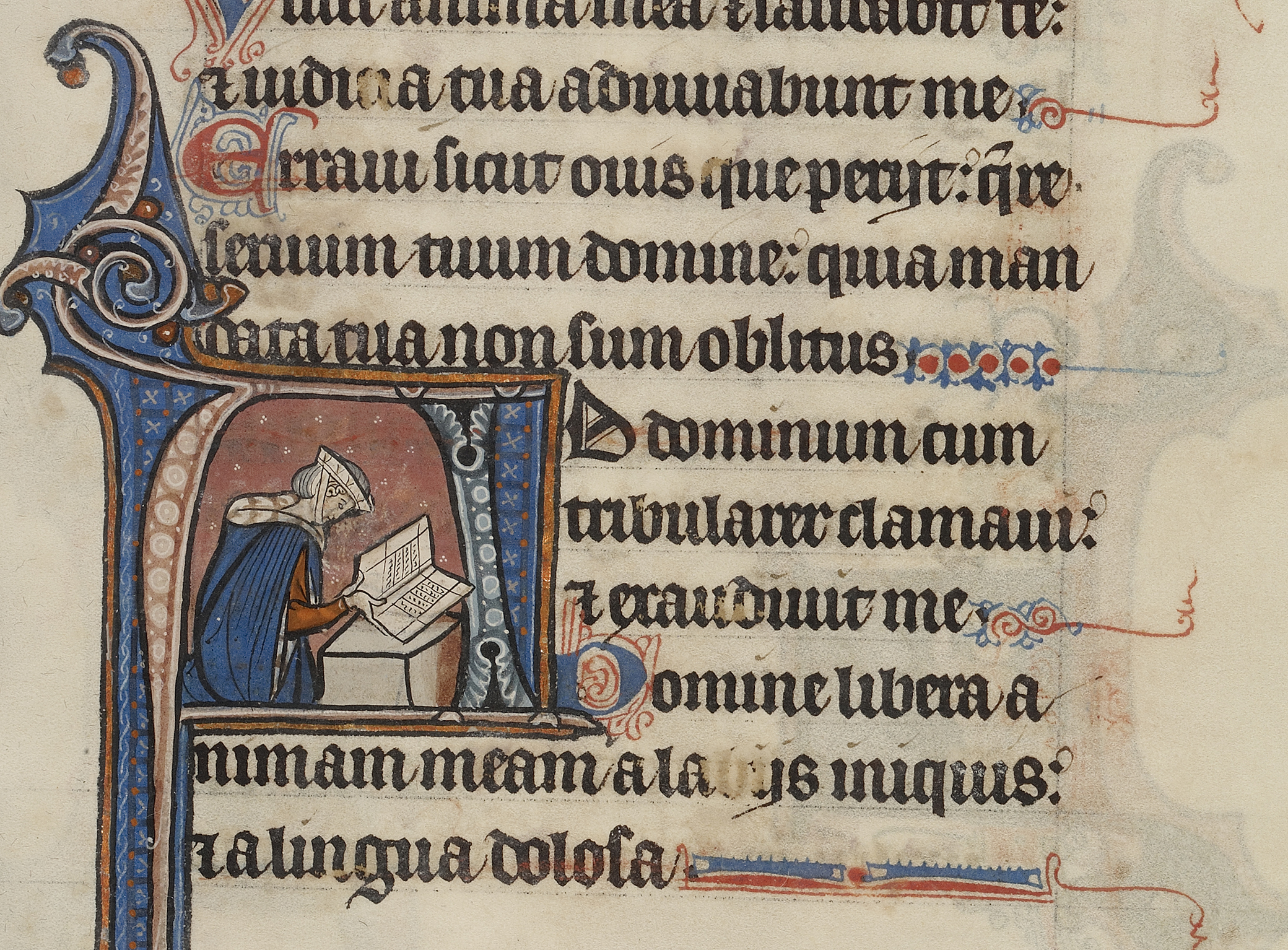

Texts from as early as the seventh century offered detailed guidance for physicians in uroscopic readings. We agree today that urine color can be an indicator of levels of hydration within the body, as well as various other measures of health, but this earlier medicine took urological divining to extremes. So focused were some physicians on reading urine that the round-bottomed flasks in which patients’ samples were presented to them quickly became a prominent part of their visual culture. Much like a modern white coat, a person in a medieval manuscript depicted peering at such a flask instantly identified themselves as a physician, although this was not necessarily a reifying gesture of respect.