Courtesy of the Office of Public Affairs and Communications, Yale University.

Millennia before the Columbian Exchange brought potatoes, tomatoes, maize, and pepper from the New World, many of the Old World’s core food plants and animals were domesticated in the region of Upper Mesopotamia in what is today Turkey, Syria, Iran, and Iraq. This includes barley and wheat, sheep, goat, cow, and pig, which to this day account for more than half of all calories consumed by humans on the planet.

It is therefore not surprising that the oldest known culinary recipes also come from ancient Mesopotamia. These recipes can be found on a group of clay tablets kept in the Yale Babylonian Collection.

Dishes known from ancient Mesopotamia include breads, cakes, pies, porridges, soups, stews, and roasts. A larger proportion of the food than is the case today was probably eaten raw. Unlike the modern Western tradition, there seems to have been no essential distinction between sweet and savory dishes, and no conventions about the order in which to eat them. As in many other traditions, presentation took precedence over order, with many dishes served together and continuously during a seating. Texts often reflect a close concern for the form and appearance of food, and elaborate utensils and molds found in excavations show great attention to its visual display

A cuneiform text about a Babylonian jester includes a passage, sometimes referred to as “The Infernal Kitchen,” that presents a series of caricature menus clearly meant to combine authentic elements with burlesque and evidently disgusting ones to create a comic mockery of the preparation and presentation of food. A short excerpt will suffice:

Month of Kislīmu, what is your food?

—You shall eat donkey dung on bitter garlic and chaff in spoiled milk.

Month of Tebētu, what is your food?

—You shall eat the egg of a goose from the poultry house resting on a bed of sand and a decoction of Euphratean seaweed.

Month of Šabātu, what is your food?

—You shall eat still hot bread and the buttock of a donkey stallion stuffed with dog poop and the excrement of dust flies.

Although the recipes are obviously not to be taken at face value, they reveal both a concern with the seasonality of ingredients and an interest in combining and presenting components that presumably also went into actual cooking.

Three of the four tablets in the collection date to the Old Babylonian period, no later than about 1730 bc. A fourth tablet belongs to the Neo-Babylonian period, more than a thousand years later. The three Old Babylonian tablets were not written by the same hand, and a physical analysis of the clay shows that it originated from at least two different sources. The tablets all list recipes that include instructions on how to prepare them. One is a summary collection of twenty-five recipes of stews or broths with brief directions. The other two tablets contain fewer recipes, each described in much more detail. All three tablets are damaged, and only the summary tablet with the stews preserves a few recipes in their entirety. The reason why the recipes were compiled is unknown, and so far, the collections that they represent are unique.

Cooking the recipes, even to the best of our ability, may not reproduce the almost four-thousand-year-old dishes in a form close to the intended one. After all, the cultural chasm that separates us from their authors is so wide that it may be impossible to bridge. Taste, aesthetics, even the fundamental ways of cooking, change over time. On the other hand, several factors work in favor of the experimental approach. A first obvious point is that the physical and chemical processes of food preparation remain the same. Charring, boiling, fermenting, caramelizing, salting, or baking all follow certain principles that do not change. Second, although taste is heavily influenced by culture, there is a set of outer bounds to what is acceptable to the human palate. We are able to detect bitter-tasting compounds at molecular concentrations that are a thousand times lower than many sweet-tasting molecules. Too much of a given taste is simply off-putting, and although sensitivities may vary, the physiology of our taste buds presents an upper limit to how bitter or salty food can be.

Third, each time we cook a given recipe, it comes out slightly different. Consistency takes years to achieve and is rarely perfect. With a given set of simple ingredients, it is therefore likely that with some experimentation we can get within the parameters of what would have been an acceptable and recognizable version of the given dish. And finally, like most other intangible cultural traditions, core procedures and customs can sometimes last for centuries and even millennia. The obvious danger of overinterpretation based on the faulty view of contemporary tradition as an “ethnographic deep freezer” can to some extent be alleviated through careful study of continuities as evidenced, for example, in classical and medieval sources from the region.

Comparing the Babylonian recipes to what we know of medieval cuisine and present-day culinary practices suggests that the stews represent an early stage of a long tradition that is still dominant in Iraqi cuisine. Today’s staple of the region is stew, aromatic and flavorful, cooked with different cuts of lamb, often slightly thickened, enhanced with rendered sheep’s tail fat, and flavored with a combination of spices and herbs and members of the Allium family, such as onion, garlic, and leek. These seem to be direct descendants of the Babylonian versions found on the culinary tablet with stew recipes.

Like most premodern cooking manuals, the Babylonian recipes rarely list the quantities of each ingredient, and so basic experimentation is needed to determine viable proportions for the assembly of a dough or the salting of a stew. The “experimental” approach likewise offers answers to questions that can only be addressed through trial and error. For example, many of the identifications of herbs proposed by modern scholars are based mainly on medical compendia, and some of the plants thus identified can produce an extremely bitter or perhaps pungent taste when used in food.

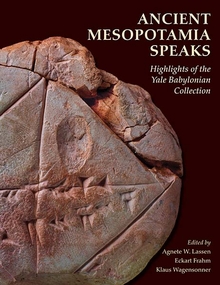

Here we translate and comment on four recipes from the Yale culinary tablets. Cooking instructions are the result of our repeated experimentation in a modern kitchen. The tablet with the stew recipes abbreviates instructions to a minimum, and nouns are not always inflected in the correct grammatical case, not unlike many modern food recipes.

Recipe for pašrūtum “Unwinding”

This is a simple recipe and one of just four largely vegetarian dishes on the tablet. Before serving, some dried sourdough is crushed and added to the dish for richness and flavor. The recipe comes out fairly bland, but with a pleasant mild taste of cilantro and onion. It looks to be a kind of “comfort dish” known also from later medieval tradition. Perhaps this explains the name of the stew, or perhaps the “unwinding” refers to what happens when the dried sourdough is added to the soup before serving. One can experiment with the proportions of the ingredients, but lots of leek and cilantro works well.

Recipe for m. puhādi “Stew of Lamb”

![Courtesy of Klaus Wagensonner. Courtesy of Klaus Wagensonner. Stew of lamb. Meat is used. You prepare water. You add fat. You add fine-grained salt, dried barley cakes, onion, Persian shallot, and milk. [You crush] (and add) leek and garlic.](https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/sites/default/files/09-14_lambstew_new_0.jpg)

This is also a simple recipe. The cut of meat is not specified. We chose shanks. For risnātu, we used parboiled barley mixed with emmer flour and fat and toasted into small hard cakes that were later crumbled into the dish. The meat is sautéed in sheep’s fat, and then the barley and vegetables are added. Finally, whole milk is poured in, and the cakes are crumbled into the stew. As the pot is left to simmer for a couple of hours, the milk curdles, and the meat and grain soften. The resulting dish is delicious when served with the peppery garnish of crushed leek and garlic. The plural noun risnātu is derived from the verb rasānu (“to soak, to steep”) and clearly refers to a function in the dish—“soakies” or the like. We could have used wine, water, milk, or beer to soak the grain and join it through pressure to produce the risnātu. We know from other texts that the cakes could be spicy and variously scented, but because nothing is specified by the recipe, we chose a neutral option to intrude the least on the overall taste of the dish. We broke up and crumbled the cakes to incorporate them in the broth and allowed a few to dissolve in the dish on their own for texture.

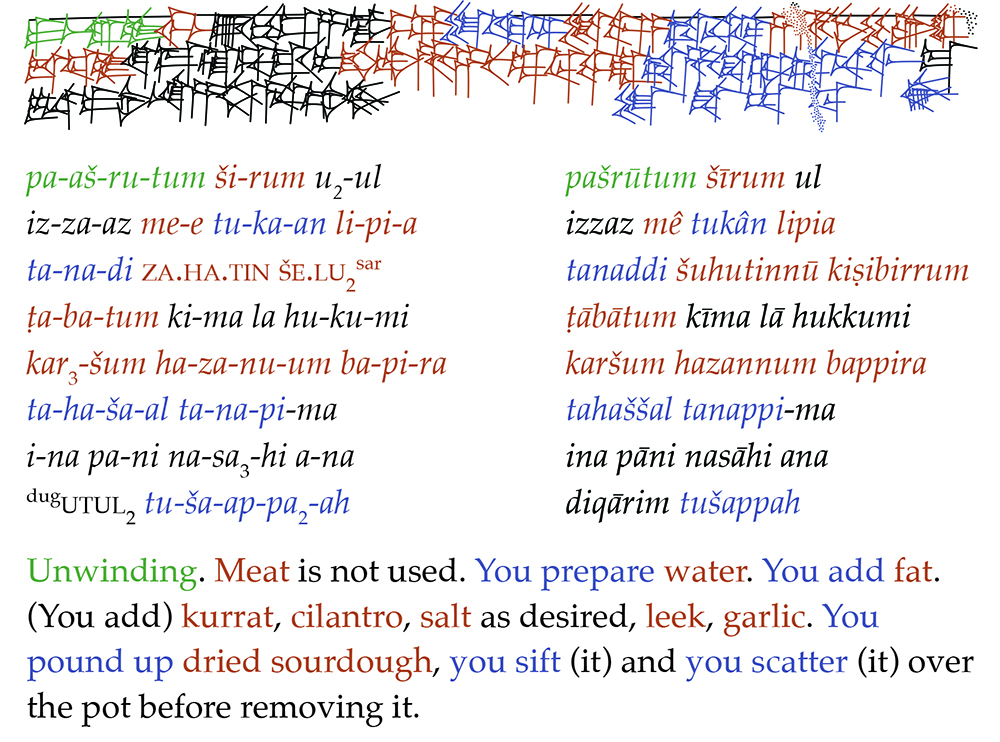

Recipe for m. elamūtum “Elamite Broth”

Blood is not a common ingredient in modern Western cooking and can be hard to find. It is prohibited in Jewish and Islamic tradition and is not found in Iraq today. We could only get pig’s blood, but the blood of sheep would be better. The mixture of sour milk and blood may sound odd, but the combination produces a rich soup with a slight tartness. The reason we include it here is mainly for its foreign origin—Elam in modern-day Iran—and its use of dill, which otherwise is not among the ingredients on any of the tablets.

Recipe for “Tuh’u”

![Courtesy of Klaus Wagensonner. Courtesy of Klaus Wagensonner. Tuh’u. Leg meat is used. You prepare water. You add fat. You sear. You fold in salt, beer, onion, arugula, cilantro, Persian shallot, cumin, and red beet, and [you crush] leek and garlic. You sprinkle coriander on top. [You add] kurrat and fresh cilantro.](https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/sites/default/files/09-16_tuhu_new.jpg)

The meaning of the name of this dish is unclear. A similar stew is made to this day in Baghdad using white turnip instead of red beet. The Jews of Baghdad before their expulsion used red beet. It is tempting to link the recipe to the continental European borscht with its close ties to the Ashkenazi community. We have cooked the stew many times with students, and the recipe works well for large groups by scaling the ingredients. Students brewed a beer using barley and left it to ferment for a few days. The result was a light drink with some acidity and only trace amounts of alcohol. The closest modern substitute in terms of taste is perhaps a mix of sour beer and German Weissbier. Bitter India Pale Ales will not work. The garnish is raw and crunchy and adds peppery zest, and the coriander seed releases a perfumed flowery taste when crushed.

Our recipe includes the following ingredients:

1 pound of diced leg of mutton

½ cup of rendered sheep fat

½ teaspoon of salt

1 cup of beer

½ cup of water

1 small onion, chopped

1 cup of chopped arugula

1 cup of chopped Persian shallot

½ cup of chopped fresh cilantro

1 teaspoon of cumin

1 pound of fresh red beets, peeled and diced

½ cup of chopped leek

2 cloves of garlic

For the garnish:

2 teaspoons of dry coriander seeds

½ cup of finely chopped cilantro

½ cup of finely chopped kurrat

The instructions are:

Heat the fat in a pot wide enough for the diced lamb to spread in one layer. Add lamb and sear on high heat until all moisture evaporates. Fold in the onion, and keep cooking until it is almost transparent. Fold in red beet, arugula, cilantro, Persian shallot, and cumin.

Keep on folding until the moisture evaporates and ingredients emit a pleasant aroma. Pour in the beer. Add water. Give the pot a light stir. Bring the pot to a boil. Reduce heat and add leek and garlic that you crush in a mortar. Let the stew simmer until the sauce thickens after about an hour. Chop kurrat and fresh cilantro and pound them into a paste using a mortar. Ladle the stew into plates and sprinkle with dried and coarsely crushed coriander seeds and the finely chopped kurrat and cilantro. The dish can be served with steamed bulgur, boiled chickpeas, and naan bread.

From Ancient Mesopotamia Speaks: Highlights of the Yale Babylonian Collection, edited by Agnete W. Lassen, Eckart Frahm, and Klaus Wagensonner, distributed by Yale University Press for the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History in April 2019. From chapter nine, “Food in Ancient Mesopotamia: Cooking the Yale Babylonian Culinary Recipes,” by Gojko Barjamovic, Patricia Jurado Gonzalez, Chelsea A. Graham, Agnete W. Lassen, Nawal Nasrallah, and Pia M. Sörensen. Reproduced by permission.