Ms. Clara Nelson at the Dead Letter Office, 1916. Photograph by Harris & Ewing. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

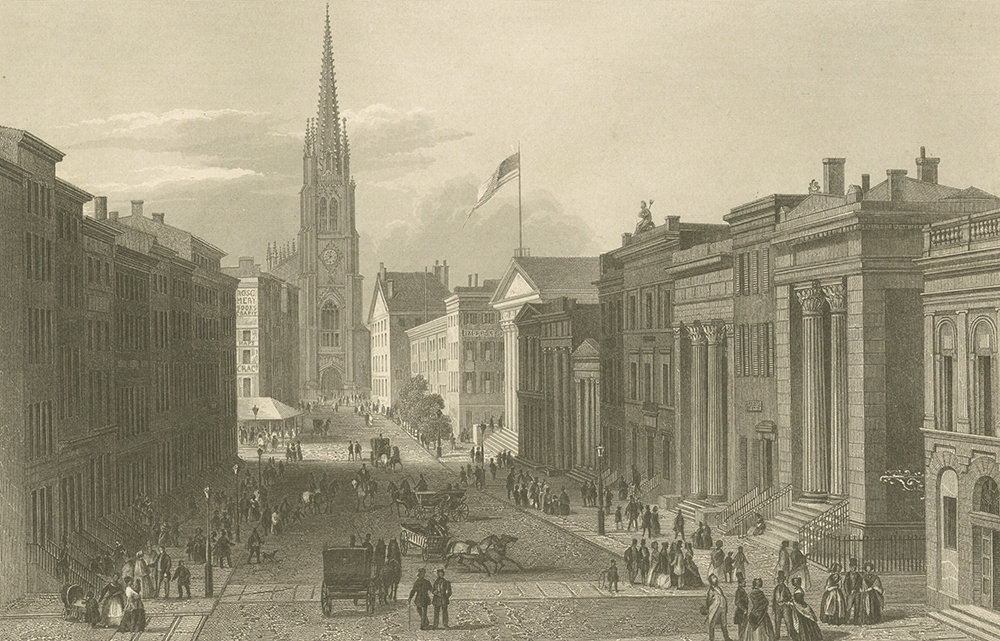

In August 1991, Judge Gerard Louis Goettel of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York handed down a curious opinion. The case involved Carl Icahn, the billionaire corporate raider, Gordon Gekko inspiration, and future special economic adviser to President Donald Trump. For the previous six years, Icahn had been staging a famously hostile takeover of Trans World Airlines. Having gained enough shares to name himself chairman of the board, Icahn took TWA private, personally netting nearly $500 million in profit while driving the company $540 million in debt. The case came to Judge Goettel when one of the company’s creditors, Mercantile-Safe Deposit and Trust, sued TWA for refusing to pay for an order of new plane engines. Icahn, not one to back down from a fight, would neither return nor to pay for the parts, arguing that the court couldn’t force him to do either.

Judge Goettel wouldn’t have it, calling the refusals “one of the most outlandish arguments this court has seen in almost twenty years on the bench.” Goettel opened his judicial opinion in the usual way, citing parallel and precedent. Unusually, though, he referenced not legal casebooks but Herman Melville’s story “Bartleby, the Scrivener,” which, Goettel pointed out, “coincidentally is subtitled ‘A Story of Wall Street.’ ” The tale features the inscrutable Bartleby, who, per Goettel’s paraphrasing, is “asked by his employer to examine a document” but responds “with the familiar refrain: ‘I would prefer not to.’ ” Expounds the judge,

This continues for a period of time and the employer becomes increasingly more exasperated. Finally, Bartleby is fired. When asked to leave, however, Bartleby again responds, “I would prefer not to.” Bartleby never says, “I can’t do it,” only that he would rather not…TWA admits it owes the money and that it has the money, but like Bartleby, it would prefer not to pay. Instead, it wants to use the money for other purposes…Would that we could all treat our creditors in a similar fashion…Unfortunately for all debtors, this is not the state of the law.

Melville’s incomparable story, which he published anonymously in 1853 in Putnam’s Magazine, is famously difficult to pin down. Bartleby is so inscrutable as to appear unthinking, even inhuman. This uncanniness is one reason why Melville’s odd story is cherished like few others in American literature. Generation upon generation of literary scholars and armchair intellectuals have foisted their interpretations—Marxist and Protestant, biographical and bibliographical, abolitionist and transcendental—upon sad Bartleby, he who is unable to confirm or deny whatever theory is applied. Judges, scholars of a specific literature, are no different in bending Bartleby to their will. For such agents of the judicial system—which relies on faith in the comprehensiveness, consistency, and efficacy of its particular set of rules—interpretation tends to focus on the scrivener’s resolute noncompliance. If Bartleby as a literary character is an open sign who gestures toward an unknown, Bartleby in the legal sense signifies what the law abhors: an action that cannot be compelled, a docket that cannot be resolved, a citizen who cannot be summoned in full—and thus can only be held in contempt.

Arguably—because all things pertaining to it are arguable—“Bartleby” is a story that exposes seams in a basic compact of American society, one continuous from Melville’s time to today. That is: a citizen “signs” a contract to follow laws in exchange for such benefits. Should one side fail to uphold its end of the bargain, the return may be void. In this frame of mind, Melville’s narrator, an unambitious lawyer running a small, unexceptional law copy shop, expects the newly hired Bartleby to ably perform his scrivener’s duties in exchange for his salary. Though shy and withdrawn, Bartleby is at first an industrious copyist. When his boss asks him to check the accuracy of a document—“an indispensable part of a scrivener’s business,” we’re told—he begins his descent into dissent. And it’s here, at the juncture of duty and preference, reason and the utter lack of it, where Icahn and Bartleby, two characters at opposing poles of American exceptionalism, are tethered, the insubstantiality of their refusals carrying equal weight in the eyes of the law. The exploits of Icahn, a wealthy and powerful financial actor, are infamous, but the record is littered with other instances of judges citing Melville’s poor Bartleby. For the law, it would seem, it matters not whether these Bartlebys are a person or organization, powerful or impoverished, defendant or plaintiff—the operating factor is the nature and extent of impedance.

See: when the Department of the Interior stated that it would not revisit the decision to return a parcel of ancestral land to the Mechoopda Indian Tribe simply because the matter had already been reviewed. Judge A. Raymond Randolph wrote in 2010 that the department’s response showed no signs of “reasoned decision-making.” By this lack, “it had all the explanatory power of the reply of Bartelby [sic] the Scrivener to his employer: ‘I would prefer not to.’ Which is to say, it provided no explanation.”

See: Judge Iain D. Johnston, a magistrate judge in the Northern District of Illinois, who became irritated when an uncommonly dispassionate expert witness answered cross-examination with only “terse comment.” The witness, a family practice doctor named Gilberto Munoz, had hedged under oath, only going so far as to claim certain medical symptoms crucial to the case were “very unlikely.” This displeased the judge, who complained that “like Bartleby the Scrivener,” this witness “did not offer an explanation for this conclusion, nor did he express any doubts or qualifications.”

See: when a case involving a property-maintenance dispute between Deutsche Bank and the New York City Department of Housing Preservation and Development reached the desk of Judge Philip Straniere of the 2nd Civil Court District on Staten Island in 2013. Straniere complained that the bank, accused by the city of failing to maintain two rental properties, had consistently relied on the word may on a foreclosure document so that when an action was required of it, the bank “elected to do nothing.” Deutsche Bank had asserted, he wrote—naming the phenomenon Goettel had struggled with more than two decades earlier—“the Herman Melville ‘Bartleby the Scrivener’ Defense.”

The law is a literary criticism in its own right; judges build rulings out of an interpretive chain of precedent. A decision can be traced, like the evolution of a species through the fossil record, back through preceding case law. Bartleby, however, stands contrary to precedence; he is ex nihilo. His employer seeks explanation, futilely demanding an exculpatory glimpse into Bartleby’s past, but he finds nothing except a mysterious rumor of time spent at the “Dead Letter Office,” where undelivered mail is sorted for the incinerator. Facing an adversary offering scant evidence of a past or even presence of mind, even the most conciliatory lawyer is unable to resolve his predicament, no matter the method—not by bribing, nor violence, nor patient indulgence.

But where Melville’s narrator is undecided about how to proceed, the court is certain. The court detects dissidence in mystery, danger in noncompliance with procedure. Incomprehensibility of Bartleby’s ilk is anathema to the order of the law, and those who offer no reason for their delinquencies are repeatedly made examples of.

Bartleby is referred to again and again in court records, where he is not evoked as a signal of ambiguity but reduced instead to pure obstacle: a bad citizen whose intentions cannot be surmised. There is no room in law for something beyond logic, because rational explanation is the key to argument. As the great English jurist Edward Coke said, “Reason is the life of the law, nay the common law is nothing else but reason.” So Bartleby, as a character stripped down for parts and recast by judges as an illicit foe, simply cannot be allowed to stand.

This is how Judge Salvador E. Casellas, of the U.S. District Court of Puerto Rico, reacted when encountering a Bartleby-esque situation in 1997. A ring of counterfeiters in the Caribbean had been caught spreading fake Reebok sneakers across the globe. Rather than argue a defense, the bootleggers engaged in what Casellas called a “keystone cops-scenario [sic]” to delay judgment for as long as possible through various schemes, such as continually extending and then deliberately missing deadlines to submit documents. Most egregiously, they “drag[ged] plaintiffs’ counsel back and forth across the Caribbean to attend defendants’ depositions in the Dominican Republic, only to refuse to sit for the depositions because plaintiffs had not secured a stenographic machine,” despite the defendants fully knowing none were available in the entire country. Fed up, Judge Casellas—like Goettel six years earlier—compared himself to Melville’s narrator, writing, “In such a similarly infuriating situation we found ourselves in the present case, with the Court and plaintiffs alike ordering defendants to comply with the litigation process, and the defendants continuously replying: ‘We’d prefer not to.’ ” Casella’s opinion furthers the argument:

Unlike Melville’s character, who eventually reconciled himself with Bartleby’s eccentric recalcitrance, we decline to condone such behavior…Rules are rules—and the parties must play by them…Like a modern-day Bartleby, counsel Martinez Tristani…figuratively replied, “I would prefer not to address those issues but rather talk about the lack of jurisdiction.” Such nonchalant behavior this Court will not tolerate.

Casellas speaks the name of Bartleby in its purest legal form: as a perfect epithet when a judge who cannot get the answers demanded by oath. Those who burden the system through disobedience may fall prey to this legal pejorative, a name-calling suitable from the bench.

Seeing that Bartleby “means no mischief; it is plain he intends no insolence; his aspect sufficiently evinces that his eccentricities are involuntary,” Melville’s lawyer narrator grants Bartleby an exemption from even “the most trivial errand of any sort.” It is not an easy choice, but as a Christian and a lay philosopher, the lawyer believes that some things are worth putting above the perfunctory contract—namely Bartleby’s human dignity. This proves to be a serious error—one the judicial system, in its concrete operation of unremitting rule following, tends not to commit. Unable to deal expeditiously or conclusively with Bartleby, the narrator quickly finds himself on the precipice of ruination. His professional reputation has suffered greatly as the rumor of Bartleby spreads, and he’s soon losing commissions to more resolute peers. Should Bartleby, the man without precedent, not be removed from his professional life entirely, the lawyer may lose everything.

This loss of standing is akin to one feared by judges encountering a Bartleby in their courtrooms. In flattening out the character to serve as a specter of reprehensible diffidence and ineradicable insubordination in their decisions, judges also enhance his power and expand his reach; a Bartleby in the courtroom is a dangerous menace and a threat to the whole system. Each new Melville reference in a judicial opinion widens the legal definition of Bartleby; with these shifting invocations, judges can leverage the character to express annoyance at any figure they regard as conniving or withholding. The rule of law requires, a judge might insist, active participants; passive resistance to its machinations must be punished in kind.

The case of such a Bartleby is embodied in factory-line inspector Angela Powell-Pickett, who brought a 2013 suit against her employer AK Steel for harassment, retaliation, and termination “based on her race, gender, [and] disability.” Powell-Pickett had been hired as a replacement worker after AK Steel locked out the steelworkers’ union. After the union returned, she applied for but was denied a promotion to shift manager, which was given instead to another black female replacement worker. Powell-Pickett continued inspecting the line.

When she was hired, Powell-Pickett was subjected to a requisite medical examination. She passed, and though it’s unclear what she included in her medical history, she promised it was complete and accurate. When she later asked for a month’s medical leave and complained during an exam of “an old workplace injury,” AK Steel fired her for providing an incomplete medical history during her first exam. The union considered her case but declined to intervene.

Powell-Pickett sued the plant not only over the medical history—AK Steel had violated the Family and Medical Leave Act, she claimed—but also for the promotion she didn’t get. It’s an ugly suit. Powell-Pickett argued she was

being discriminated against and harassed because of her race and gender…subjected to racial slurs and sexist comments…subjected to unwelcome and offensive touching. Her locker was sprayed with profanity directed at [her] gender. An employee urinated in containers and placed them in the ceiling above [her]. A noose was found hanging in her work area.

But when questioned by AK Steel’s attorneys, Powell-Pickett wouldn’t defend her own claims. In response to questions about why she thought she was harassed or retaliated against, she answered, “I don’t recall at this time” at least five times. Asked what proof she had that she was fired because of filings she had made with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, she responded, “That’s just what I feel.” To AK Steel’s lawyers’ question “Do you have any other reason why you feel that way?” Powell-Pickett answered, “I have plenty of reasons.”

“Well,” said the lawyers, “now is the time to tell them.”

“Don’t recall them at this time,” she responded.

The suit was struck. Judge Robert H. Cleland wrote in his opinion that “although there exists some evidence of objectively cruel behavior, Powell-Pickett, principal saboteur of her own deposition, made a record bereft of evidence that she considered her workplace hostile or offensive.” The law, that is, can do nothing for those who will not help themselves. A more humane system might have interrogated Powell-Pickett’s abrupt change of heart. Why didn’t she withdraw her case? Then again, asking such questions didn’t turn out well for either Bartleby or his hapless guardian. When Cleland ruled against the complainant, he echoed his peers by concluding, “Her approach brings to mind the attitude of Bartleby…who reflexively responded to every request, ‘I would prefer not to.’ ”

Reflexively seems the operative word—and one that may clarify the proliferating use of Bartleby on behalf of the bench. It lays bare an assumption of thoughtlessness, casting aside anyone who does not properly self-advocate, who cannot provide reasons for their behavior. In such an application, Melville’s Bartleby is finally, ultimately reduced to little more than a boy with a bad attitude, refusing to play by the rules.

Simplified into such thoughtless, knee-jerk beings—or just jerks—Bartlebys dot the record. In Savannah, Georgia, a nuclear medicine technologist who sued his employer for wrongful termination was deemed by a judge to be “a nightmare employee, cut from the same cloth as Herman Melville’s Bartley [sic], the Scrivener” after the court discovered he had made “disparaging remarks to” and sexually harassed coworkers. In 2008, Judge Vanessa Ruiz, of the DC Court of Appeals, saw a Bartleby in Aundrey Burno—who had shot a police officer through the neck at point-blank range during a botched bodega robbery—when he attempted to plead the fifth after waiving his Miranda rights. A judge in Washington, DC, found a Bartleby not in the man appealing his fifteen-to-life sentence for the rape of a minor but in an actual law copyist whose typo left out a statute’s provision about sodomy, threatening the validity of the state’s position. In a 2007 child custody case in Westchester, New York, a mother became like Bartleby when she “ ‘preferred not to’ interact with her attorney, hire a new attorney, execute releases, contact the law guardian, or participate in the Court proceedings, and, like Bartleby, has suffered the consequences when matters (and life) proceeded forward despite her absence.”

In Montgomery, Alabama, when attorney Norman Hurst Jr. signed on in 2007 to represent a preschool teacher in a race and gender discrimination suit against First United Methodist Church but then missed every court-appointed deadline, skipped pretrial hearings, and ignored every request to discuss settlements, Judge Myron H. Thompson declared, “The court cannot look into Hurst’s mind.” Seeing Hurst as his colleague, he at first gave Hurst “the benefit of the doubt” until, finally, he could no longer:

Prior to the hearing, [Hurst] called the court’s chambers and left a message, unwittingly, perhaps, in the words of Melville’s Bartleby the Scrivener, that he would “prefer not” to attend the contempt hearing. The court sent a message back that he had no preference in the matter and must attend the hearing if he did not want to be held in contempt of court.

Some people cannot be persuaded. Hurst was late for the hearing and sanctioned for contempt, another Bartleby cut down before he could do more damage.

Though he’s the title character, Bartleby is not the only copyist in Melville’s story. The narrator has two other scriveners in his employ, men who may toe the line: one, Turkey, is an alcoholic who is useless after lunch; the other, Nippers, while productive in the afternoon, lacks premeridian focus due to “indigestion.” But they believe in and abide by their contract, and the narrator willingly accommodates their peculiarities. After Bartleby begins to shirk his work, Nippers and Turkey dutifully offer to bash in Bartleby’s face. A central piece of the narrator’s difficulty in dealing with his wayward employee is that he knows Turkey and Nippers may come to view him as a pushover boss and organize an office mutiny.

A Bartleby figure, after all, does not operate in a vacuum. Melville’s narrator struggles to control the situation among three employees just as judges fear the spread of hindrance—that stoppage of the gears of justice in the face of widespread fecklessness. Perhaps there’s something to this—not just Bartleby as an archetype but as a diagnosis. Law theorist Amy D. Ronner has written of “cadaverous Bartleby clones” that populate a legal profession rife with “toxic atrocity.” After graduating from the pressures of law school, Ronner theorizes, new attorneys are thrust into an “arena that engenders drones, like Bartleby, who become voiceless, invalidated, and stripped of volition,” and who, like Bartleby, live in the office and suffer from depression and suicidal impulses (not to mention, she notes, eating from the garbage, not eating at all, alcoholism, numbness, friendlessness, joylessness, spiritual deprivation, and “squelched ambition”).

One possible cure for Bartlebys, Ronner proposes, is retranslating Bartleby back from legal scholarship to literature—making law students read “Bartleby” the story. “Melville’s story,” she writes, “might just be the most important assignment for all lawyers,” for reading it will help future lawyers to

recognize Bartleby syndrome, detect the symptoms of learned helplessness, and fend off the very thanatotic forces that pulverized Melville’s scrivener. In turn, such graduates can learn to demand and even create future workplaces that aspire not to mint Bartleby clones in the form of invalidated, voiceless, and depressed lawyers.

Ronner may share the court’s ultimate goal of a functioning body politic. Unlike the court, however, she sees Bartleby not as outlier but as symptom: a side effect of the courts, employers, and other official institutions that, in attempting to build and sustain an efficient machinery of governance, have created a procedure for breaking people down to better fit into molds. As Judge Cleland himself observed, the steelworker Angela Pickett-Powell seems to have greatly suffered at the hands of her colleagues. But because she wouldn’t testify on her own behalf—for reasons that the court has no interest in learning—she was reduced to a Bartleby, a symbol rather than a product of disorder. The court’s obligation, these cases make apparent, isn’t to bring poor Bartleby back into the societal fold, as the employer in Melville’s story so futilely tries to do. In the law, as in the workplace, people are variables in the algebra of the contract to be moved, reduced, and figured until both sides of the equation are satisfied. Understood in this way, the powerful Icahn and the harassed Picket-Powell invite the same criticism: they are both noncompliant, and both thereby disappear beyond the limits of legal reasoning. They enter into a Bartleby vortex, a void that rejects all context.

Yet Bartleby, with all his passive rebellion—his utter refusal to take part in any aspect of what a working majority deems to be life itself—is in Melville’s story perhaps the most human character of all. Bartleby is the only one allowed a name. Our narrator is anonymous, cartoonish, and one of countless small-time operators in a profession that exists solely to document (and thereby legitimize) the law. His other employees—Turkey, Nippers, and the errand boy Ginger Nut—are no more than their nicknames, the last reduced solely to his daily task of fetching cookies. These men’s personhood matters so little that Turkey and Nippers are interchangeable, swapping personalities every day at lunch.

Had Melville set out to write a children’s book, Bartleby may have survived the story to teach the narrator—to teach all of us—how better to live through negotiation with systems, with requirements, with an employer’s demands. But adult literature is obliged to unveil darker truths. Bartleby the iconoclast cannot be allowed to survive. Like the dead letters in his previous office, Bartleby is superfluous, and the system disposes of him. In the Tombs, Bartleby is stripped of his name, called only “the silent one” by the prison staff, just as all those whom the court call “Bartleby” are reduced to a single attribute, just as how in the workplace we are our production. The irony of the contract, designed so that we may thrive, albeit within its bounds, is that its enforcers view all through its lens as objects, either fitting or out of joint. As records of our human struggles, judicial opinions are far less generous than Melville’s narrator, who at least attempted to write the complete life of a man he valued. Rather than broadly applying a character name that manages to equate the powerful (like Icahn) with the powerless (like Powell-Pickett)—who were certainly not served equal justice by the legal system—perhaps the arbiters of law should look beyond the transcript and, at least once in a while, declaim, as did Melville’s narrator, “Ah Bartleby! Ah humanity!”