On November 26, 1864, eight militant Confederate supporters set fire to several New York City hotels as part of what the New York Times called a “diabolical plot to burn the city of New York.” This round of arson was an arm of a coordinated national attack on several Northern cities intended to turn the tables on an inevitable Union victory. It was sponsored by the government of Jefferson Davis, secretly supported by many Northern politicians, and conducted under the command of combat officer Colonel Robert Martin. The fires were intended to serve as distractions in each city as Confederates concurrently raided local treasuries and sprang inmates from nearby prisons.

That night, the Winter Garden in Lower Manhattan was hosting a special benefit performance of Julius Caesar. The play featured the three Booth Brothers onstage together for the first time: Edwin, Junius Brutus Jr., and John Wilkes, the last of whom would soon commit his own egregious act of pro-Confederacy vigilantism. An alarm rang out next door in the burning Lafarge House during the performance.

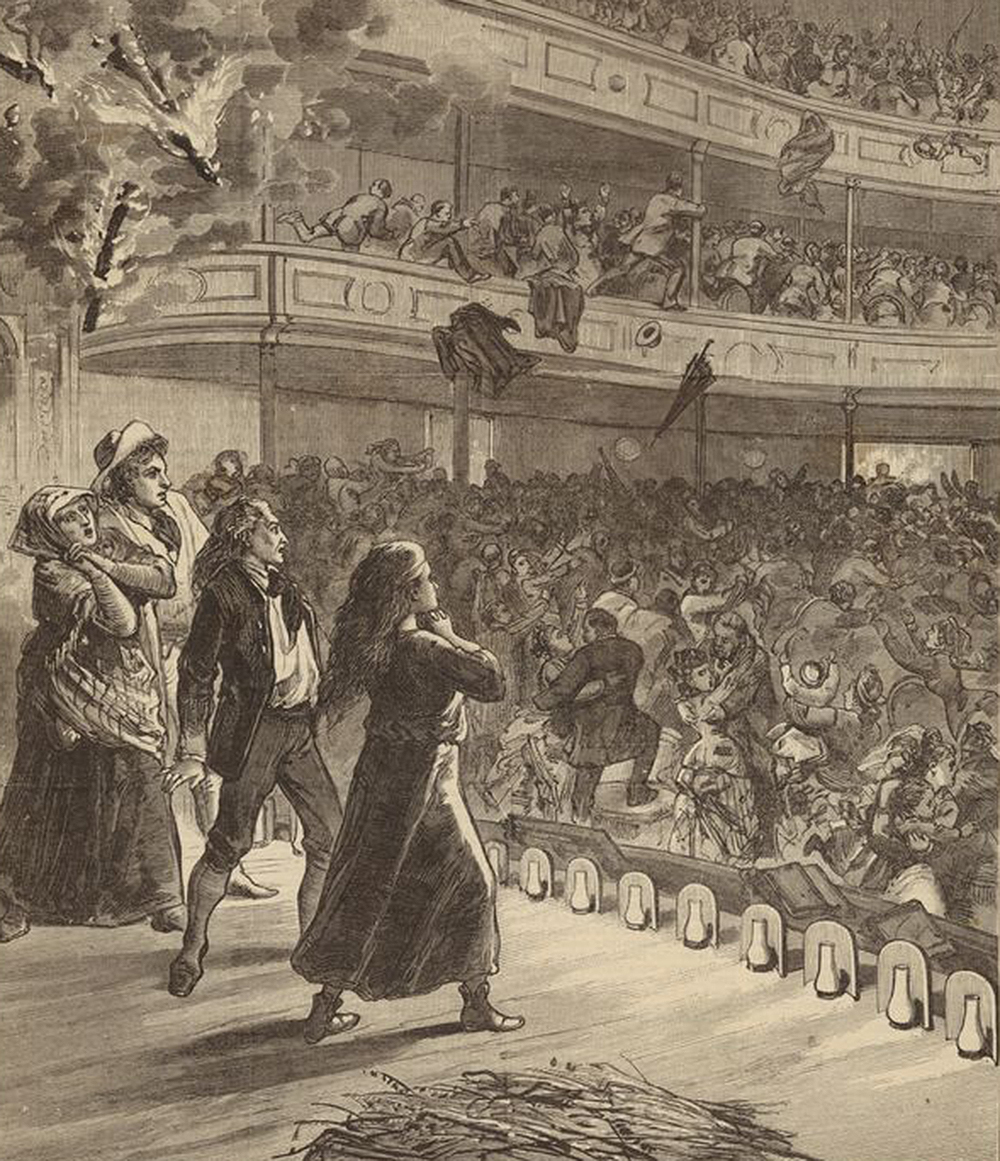

The Times reported, “The excitement became very intense among the closely packed mass of human beings,” and “the panic was such for a few moments that it seemed as if all the audience believed the entire building in flames, and just ready to fall upon their devoted heads.” The coolheaded Edwin Booth, who was watching the ensuing mania from the stage, broke character and instructed the two-thousand-person audience to remain calm.

Across the street at Barnum’s American Museum, 2,500 spectators had gathered to watch a performance. Edwin Booth was unaware that one of the Confederate vigilantes, the “Southern Hotspur” Colonel Robert Cobb Kennedy (who got drunk and went rogue, abandoning the hotel plan), had exploded a bottle of a combustible substance in the hall. The stairway caught fire, and the crowd panicked.

The substance, which emulated the ancient incendiary cocktail known as Greek Fire (believed to be a combination of naphtha and quicklime), relied on oxygen to grow. Many of the cramped spaces and closed rooms in which the blazes had begun were too confined for the fires to become very dangerous. The fires were put out quickly despite the desperate crowds causing mayhem in the streets. Of the nearly 800,000 people in the attacked venues or surrounding areas in New York, miraculously none were seriously hurt. All of the buildings remained intact. The perpetrators were apprehended.

The journalists covering the story for the Times were aware that the happy ending was anomalous, if not just extremely lucky. If the plan had “been executed with one-half of the ability with which it had been drawn up,” a reporter wrote, “no human power could have saved this city from destruction.”

Building fires, and specifically theater fires, have always been a serious risk to urban spaces. On June 29, 1613, for example, the firing of an onstage cannon during a performance of Henry V set fire to the roof of the Globe Theatre, burning it to the ground. The Gilded Age’s rampantly poor building maintenance and serious overcrowding made structures particularly susceptible to fire and dangerous, however. William Paul Gerhard, an engineer with the British Fire Prevention Committee, stated in a report that by May 1897 there had been 1,115 recorded theater fires in Europe and America (since records had been kept); there were 460 theater fires across America and Europe just from 1800 to 1877. Gerhard claimed that the average life of a theater in the United States was only about thirteen years due to fire.

American journalists repeatedly demanded that immediate architectural reform was necessary. Structures did not have enough exits or extinguishing materials, and maintenance of those that existed was often neglected. “In yesterday’s Times,” one reporter noted in 1872, “we recorded no less than twelve fires which took place in twenty-four hours and three of them were very destructive.” The most precarious of all edifices were theaters, which packed in crowds night after night and were illuminated by many small flames or, eventually, vast amounts of newly developed electrical equipment.

The Chicago Times ran an enormous front-page story about a local theater fire in February 1875, with shocking subheads like burned alive and hundreds of charred and distorted corpses. It included horrifying details about patrons’ struggles to escape and their gruesome deaths. The article turned out to be completely made up, but it wasn’t a hoax. It was a cautionary tale, printed by the newspaper in hopes of raising awareness about poor fire-safety measures in public buildings, particularly entertainment venues—a lesson no one seemed ready to learn yet.

On December 5 of the following year the Brooklyn Theater went up in flames. One of the gaslights above the stage set the drop curtain of the stage on fire. Although the actors saw the blaze, they continued the performance of the melodrama The Two Orphans until someone in the auditorium cried out, “Fire!” The performers gathered by the footlights, imploring the crowd not to panic. Then someone opened the stage doors to allow an exit. A draft blew in and flames billowed. Screaming people struggled to exit, falling over the balcony, sliding down the stairs, piling on top of one another. At least 278 people perished. The fire marshal ordered a random sample of autopsies, all of which revealed death by suffocation. The head usher, Thomas Rochford, said that he’d previously seen the room empty in seven minutes easily. The building’s architect, G.L. Morse, insisted that people should have been able to evacuate in three.

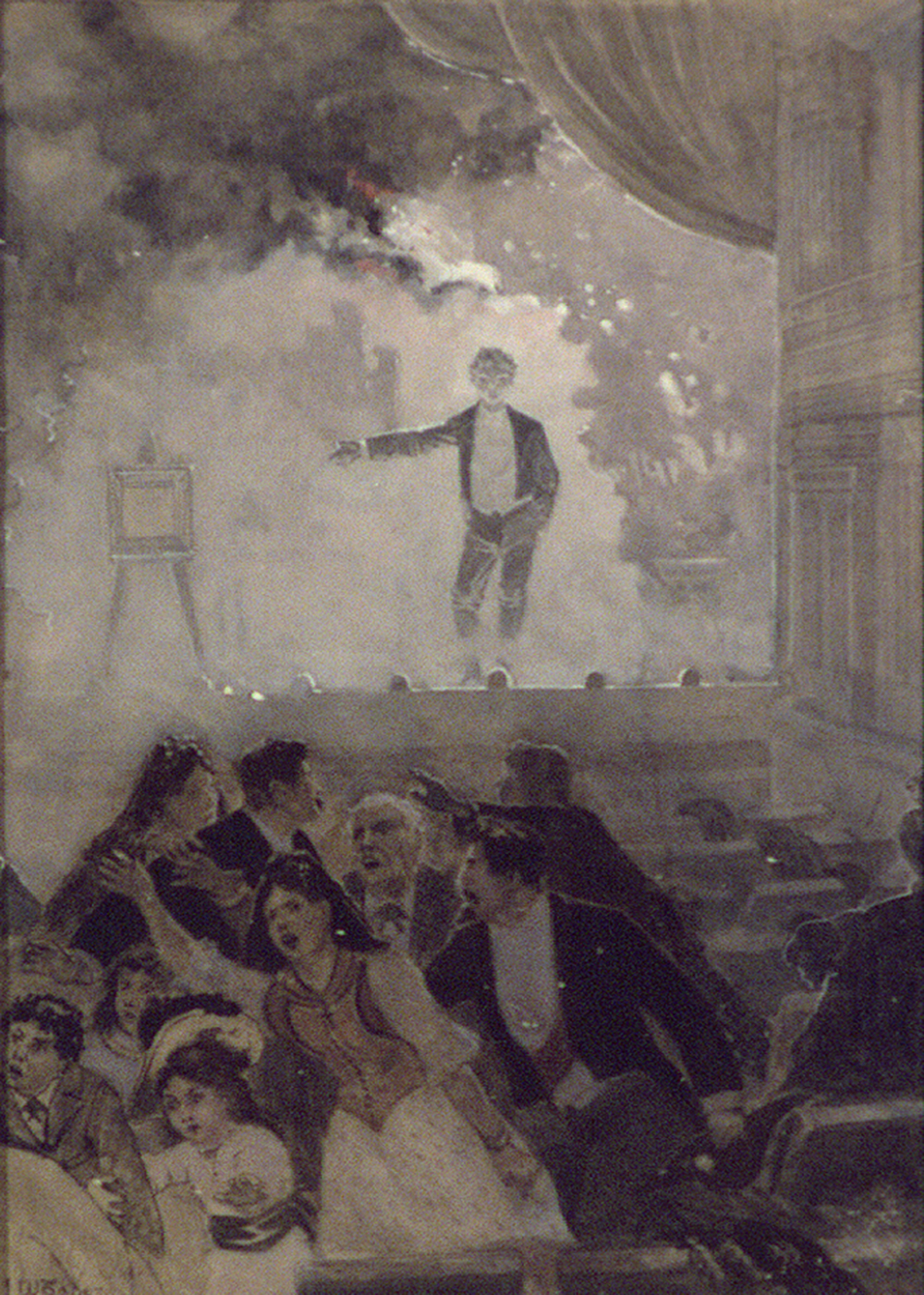

On New Year’s Eve 1903, Chicago’s Iroquois Theater was set ablaze in similar circumstances. During a matinee performance of Mr. Bluebeard, largely attended by women and children, the fuse of a spotlight burst, setting fire to the muslin “fly border” of the stage. For a few minutes, the stagehands fought to put it out—stage electrician John E. Farrell climbed up to the top of the curtain and attempted to douse the fire with his bare hands—but it quickly grew beyond all reckoning. Farrell then hurried down to the stage door, opened it, and began to evacuate everyone backstage. When other workers attempted to slide open the large backstage freight doors, they released a draft that forced the fire into the theater auditorium. Described as a “wall of fire” and a “cyclonic blast” by various witnesses, the blaze billowed into the audience, blocking many of the fire exits. Other escape routes either were not labeled, locked, or difficult to operate. Eddie Foy, the headlining comedian at the performance, ran to the front of the stage and began to try to direct people safely out of the theater. But the loft above him caved in and brought the flames to the stage, forcing him to make his own way out. At this point, the lights went out.

In just ten minutes, as many as six hundred people—more than one-fourth of the audience—perished. Most of the victims, many children or teenagers, had been trampled to death.

To combat the growing reputation of theaters as death traps, New York City impresarios began to advertise their venues by stressing just how safe they were—without changing the actual structures. In 1901 the top of the Broadway Theater’s playbills, above the production information, read “Safest theater in the world—34 exits.” That same year, the Knickerbocker’s playbills stated that it was “Absolutely Fireproof.” By 1904 the Majestic was billing itself as “New York’s finest—the world’s safest theater—positively fireproof—42 exits,” and by 1906 the Colonial was claiming it was “absolutely fireproof—this theater has the lowest insurance rate issued to any theater in the world.”

Theaters varied in size and design, but they were typically large and multitiered, had many exits, and could theoretically be emptied quickly. The impresarios relied on easy statistics to comfort audiences who were well aware of the risks of attending the theater. According to Gerhard’s report, as of 1899 New York’s Fifth Avenue Theater could hold 1,400 people but be emptied in 2.5 minutes, while the Abbey Theater could hold 1,450 people and be emptied in 1.5 minutes. The enormous Madison Square Garden, which could hold 17,000 people, apparently required only 4.5 minutes for complete evacuation.

These hypothetically efficient evacuations were impossible to execute, however. Theaters and movie theaters often were illegally packed to standing-room-only capacity, with additional bodies blocking potential routes of egress. Furthermore, Gerhard found that the doors were locked in many of the buildings, and many of the exits first wound through basements or alleyways. Some exits even led to wooden staircases. Families and young children were frequently given permission to be seated in the highest galleries, which made their top-priority exits more difficult.

On January 1, 1910, Raymond B. Fosdick, commissioner of accounts at the Bureau of Violations and Auxiliary Fire Appliances, started compiling a report on fire-safety violations in New York City’s public places at the request of fire commissioner Rhinelander Waldo. Fosdick submitted his review, titled Report on the Bureau of Violations and Auxiliary Fire Appliances, to Mayor William Jay Gaynor in early November 1911; the report’s statistics were reprinted in the New York Times on November 11. The newspaper suggested that the devastation from the 1903 Iroquois Theater fire had provided the impetus for Fosdick’s investigation. The report depressingly claimed that “practically in every theater and moving picture house, as well as in hundreds of factories which are mere firetraps at best, no pretense is made of obeying the law.”

The Bureau of Violations and Auxiliary Fire Appliances had been founded in 1903 as an extension of the Fire Department specifically responsible for fieldwork, encompassing

the examination of all complaints and reports of violations, or alleged violations, of all laws and ordinances which place upon the Fire Department the duty of requiring the installation of auxiliary fire appliances and the taking of other precautionary measures, etc., which are made mandatory by the Charter, laws, or ordinances, or are discretionary with the Fire Commissioner.

The agency was in charge of noticing and reporting violations that could have an impact on theater safety. But the report had found that the not only had the bureau failed to do this or to maintain various fire safety apparatuses, but in many cases it also had filed documents with false information. In forty-one theaters, a total of 809 fire pails were barely filled. Across eighty theaters, there were a total of 484 fewer axes than required. In many theaters, fire extinguishers often were hidden behind set pieces and therefore inaccessible. The same went for the sixty movie theaters investigated.

By the time Fosdick had completed the investigation for Waldo, there was a new commissioner in town: Joseph A. Johnson. Johnson was an unusual candidate for the job, but he was determined to make a positive impact. Originally from Atlanta and a graduate of the University of Alabama, Johnson had previously worked as a journalist, serving on the staff of the New York American and the New York World; he had been a war correspondent in Puerto Rico during the Spanish-American War. He also was a prominent figure in Tammany Hall politics, having managed mayoral campaigns for John T. McCall and John P. O’Brien.

Waldo had resigned his post in the fire department to become the new police commissioner less than two months after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire led to the deaths of 146 garment workers. It was one of 14,405 fires in New York City that year and led to a new push to prioritize fire safety and punish negligent building owners.

Governor John Alden Dix formed the New York State Factory Investigating Commission three months after the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory fire. The creation of the commission led to the passing of the Sullivan-Hoey Fire Prevention Law in October 1911, which instituted the New York City Fire Prevention Bureau and increased the power of the fire commissioner. By 1913 Johnson was ready to call a meeting of notable members of the theater industry in order to announce new mandatory theater safety practices that all venues had to adopt.

The first rule was that fire safety drills would be performed weekly, with employees (ushers, orchestra members, other personnel) assigned to specific tasks. It was proposed that all seats have cards attached underneath that stated the location of the closest exit.

Johnson explained to the group of theater owners and managers he had assembled that he believed the biggest danger to audiences during fires was not the fire itself but panic. The association of theater fires with abject panic already had been firmly solidified in the zeitgeist, where it would remain. Six years later, in 1919, U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. claimed, in Schenck v. United States, that the right to free speech does not excuse “falsely shouting fire in a theater and causing panic”—a highly curious reference to make in a case entirely unrelated to panic or fire. The case dealt with Joseph Schenck’s arrest for printing and disseminating materials encouraging men to boycott the wartime draft. The verdict upheld Schenck’s arrest and the Espionage Act of 1917, which sought to prevent nonauthorized individuals from interfering with military-related situations or ventures. “Shouting fire in a crowded theater,” as the phrase came to be known, referred in this case to the dangerous inciting cry (often with little substantiation) of an individual with no authority, which could stir a crowd to abandon protocol.

To mitigate directionless panic, Johnson told the room of impresarios that a fireman carrying a giant sign should appear onstage in every single theater before each performance. His sign would outline specific fire-safety and egress instructions, so the audience would be aware of how to calmly conduct themselves in the event of an emergency.

According to the New York Times’ coverage of the meeting, theater owner Mark Klaw gasped at this proposition. “If a fireman came out before the curtain with that,” he protested, “you never could tell what would occur. Get your audience uneasy and you never can tell what will happen.” He added that “it spoils the show.” Klaw suggested owners have the safety announcement printed on the main page of the programs instead. Johnson agreed to give the suggestion a trial period of thirty days; it was kept as a policy after.

By 1913 all New York theater playbills included the following helpful directions: “Look around NOW and choose the nearest Exit to your seat. In case of fire walk (not run) to THAT Exit. Do not try to beat your neighbor to the street.” Several years later, a second, more encouraging option began to appear: “This theater, under normal conditions, with every seat occupied, can be emptied in less than three minutes. Look around now, choose the nearest exit to your seat, and in case of disturbance of any kind, to avoid the dangers of panic, walk (do not run) to that exit.”

The negotiation of how to present fire-safety information to the public reveals an interesting development in the theater’s representation of itself within the culture of the city. Actors breaking character onstage and attempting to direct crowds, as well as actors noticing fire but nervously carrying on with their scenes anyway, expose how theater space was almost lawless and ungovernable in its commitment to entertainment and artifice. The escapism of the institution was so important to its integrity that theater managers, rather than give audiences important emergency information, insisted that such real-life disasters would never happen in a particular venue—in effect they were relying dangerously on an additional fiction to preserve the enjoyable environment of theatrical fiction. These directions acknowledge that not only were theaters potentially dangerous but also that audiences bore responsibilities as citizens inside that space—the theater space had become simultaneously a practical, civic institution and a place for escapist pastimes.

The Fire Prevention Bureau maintained its strict observance of the fire-safety protocols and made arrests for violations, including locked doors and overcrowding—catching ten theaters in 1912 that were still violating the rules. In 1913 Johnson had to shut down several theaters that resisted incorporating safety measures.

Johnson’s reforms extended beyond the theater community, and he began forming creative solutions to the prevention of many different types of fires. Trash piles found in building basements were ordered to be cleared. By 1913 Johnson and his sixty-eight-person bureau had installed 603 fire escapes and many easily accessible fire alarms throughout the city. He also began to promote an agenda against “careless smoking”; his investigators had reported “that in 1911 there were 3,332 fires caused by carelessness with cigars, cigarettes, and matches.” He posted notices in English, Yiddish, and Italian warning about the criminality of this behavior all across the city. Several months after the institution of this policy, hundreds of perpetrators had been fined or jailed, thanks to some creative problem solving around Section 1530 of the Penal Law, which allowed criminal proceedings to be taken up after those who caused a “public nuisance”—which was defined as “a crime against the order and economy of the State and consists in unlawfully doing an act or omitting to perform a duty, which act or omission: annoys, injures, or endangers the comfort, repose, health, or safety of any considerable number of persons or in any way renders a considerable number of persons insecure in life, or in the use of property.” Johnson knew that the Health Department had prosecuted people under this section and consulted the corporation counsel to ensure that the Fire Department could employ it as well.

That same year, he hired the first female fire inspector specifically to stop people from smoking in factories. (Sarah W.H. Christopher was very good at her job, catching 123 smokers in her first two months.) In 1914, due to pressure from “the Suffragettes”—in particular a settlement worker named Juliette Arden who filed a lawsuit against the department for excluding women—the Fire Prevention Bureau hired three more female fire inspectors.

Fire prevention became Johnson’s brand, and he portrayed himself as a crusader bound to end a destructive pattern. Johnson was not known exclusively for his fire-prevention work, however. After he resigned from the position of fire commissioner in 1917, he directed national publicity for the American Red Cross, became commissioner of public works, and was elected borough president of Manhattan. He served as the head of the Boxing Committee, and then, in 1930, became publicity director for the Fox Film Corporation in Hollywood. He returned to New York in 1932 and became general manager of the Triborough Bridge Authority. Yet after his death in 1942, his New York Times obituary credited him as the author of what was then a famous phrase: “Look around you now; choose your exit, walk, do not run,” a shortened version of the original direction. He was eulogized as the hero who reduced fire loss in New York City by 40 percent.

As fire commissioner Johnson had been thrilled with the results his department had accomplished so far, especially since, as he put it in 1914, “we began fire prevention as an experiment.” New York had blazed a trail, and now authorities in cities such as Cincinnati and Cleveland were interested in following suit with similar reforms. Philadelphia had even sent a group of firemen to New York to study Johnson’s plans. That New York was becoming famous for its large-scale fire-safety strategies became a point of pride.

After Johnson’s rules were implemented, fire-safety practices changed very little during the twentieth century. “Fire prevention in this city has come to stay,” he declared in 1914, adding, quite pleased: “If my prediction proves true, fire prevention will have accomplished that for which it was destined.”