Mammon, n. The god of the world’s leading religion. His chief temple is in the holy city of New York.

—Ambrose Bierce, 1911Holy Dread

The history of the United States is synonymous with the dream of riches, but the question as to whether money is mortal or immortal has never been resolved.

By Lewis H. Lapham

Our Robber Barons, illustration from Puck magazine, by Bernhard Gillam, 1882. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, Washington, DC.

Money, which represents the prose of life, and which is hardly spoken of in parlors without an apology, is, in its effects and laws, as beautiful as roses.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

If you’re bourgeois, money is it. It’s all the questions and all the answers. Ain’t no E-flat or color blue, only $12.98 or $1,000. If it isn’t money, it isn’t nothing.

—John Coltrane

The history of the United States is synonymous with the dream of riches, but the question as to whether money is mortal or immortal has troubled Americans since the early confusion in the seventeenth-century wilderness about the budget projections for what they conceived as a joint venture backed by Divine Providence and British gold. Among the companies of gentleman adventurers offloading Dutch cannon and Geneva bibles on the shores of Massachusetts Bay, there were those who had come in search of El Dorado, betting their lives, their fortunes, and their sacred honor on rumors of Spanish treasure and a trade route to the Indies. Others arrived with blueprints for the building of the New Jerusalem, content to lay up stores of virtue against the coming of the long New England winter in the grave. Visionary realtors assembling beachfront property on the coast of Utopia; stone-faced clergymen issuing passports for the journey to the pit of hell; nobody in the congregation at a loss for a sermon or a subprime mortgage deal or, if so inclined, a committee meeting about the nature and provenance of their newfound wealth—the wages of sin or a sign of grace, proof of the good Lord’s infinite wisdom, or the product of a sharp bargain with a drunken Pequot Indian.

As an heir to the ambiguity in the Puritan body politic, and as a lifelong and card-carrying member of the society alluded to by Emerson, I never know for certain whether money is an enemy or a friend. Its intentions fluctuate, and its appearance shifts in accordance with the angle of the sales pitch, the size of the number, the tone of voice and time of day, the chance of its arrival in the mail. By the age of four in San Francisco, I knew that money was the elephant always in the room, never to be addressed or seen, but whose will was done on earth as it is in heaven. At school and college in Connecticut in the 1950s, I understood that I was being groomed to meet and greet the august personage recognized by Coltrane as the Man. Resident for fifty years in the city regarded by Ambrose Bierce (also by John Adams and Henry James) as sacred to the worship of Mammon, I’ve learned to look upon money as the hero with a thousand faces, to know that nowhere under the light of the American moon or in the heat of a noonday American sun was its hallowed name to be spoken lightly or in vain.

The Miser, by Hendrik Gerritsz Pot, c. 1640. Uffizi Gallery, Florence, Italy.

Several authors in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly take the liberty of doing so, and I like to think that their presumption serves a greater good than the lighting of an Easter candle for the soul of Citibank or the falling prostrate on a prayer rug in Dubai. Although I know that it ill becomes a true American to find fault with the dream of riches that wins presidential elections and waters the deserts of California, I also know that the accumulation of too many converts to “the world’s leading religion” (like the too abundant concentration of methane gas released by the livestock in the nation’s feed lots) sucks the oxygen out of the atmosphere and wilts the roses. Transfer to money the properties of mind and spirit for which it often stands as surrogate—the freedoms of thought, the play of the imagination, the consolations of philosophy—and sooner or later it comes to pass that instead of the people owning the money, the money owns the people. The poor return on the investment sinks to the bottom lines reported in the newspapers under the headings of war in Afghanistan and Iraq, panic on Wall Street, the deteriorating health and happiness of the American people, the depreciating value of the American dollar, the melting of the Greenland ice sheets, and the disappearance of the honeybees.

If it’s nothing new to say that the fervent love of money results in predictably high yields of stupidity and fear (the Bible is explicit on the point, as were Aristophanes and Adam Smith), what comes as a surprise is the news that we seem to have constructed a universe requiring us to inflate the lovelorn speculation to record highs. Over the course of the last century, the immense expansion of the world’s money supply has been produced by correspondingly immense extensions of credit, which in turn demand increasingly generous suspensions of disbelief. As opposed to objects that can be firmly grasped—jewels, furs, gold coins, captive women—wealth consists of nothing more substantial than the icons making cameo appearances on Google. Jack Weatherford’s essay, “

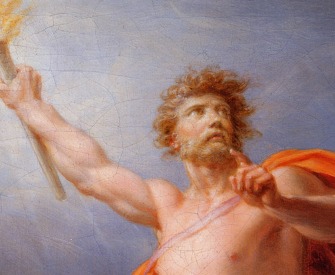

Prometheus Unbound,” speaks to the vast but invisible cloud of energy set free in the international currency market, $3.2 trillion orbiting the globe at the speed of light—money as pure spirit, immaterial and transcendent, trading at all hours of the day and night (if not in New York or London, then in Hong Kong, Sydney, and Mumbai); the sum of mortal man’s desire compacted into immortal abstraction, unburdened by the need to plant a crop, dig a well, reap a harvest, destroy a castle, or build a church. The flesh becomes word, and in the metaphors inscribed on its computer screens, the modern world finds a digital analogue for the revealed truth streaming down upon the medieval kings of France through the stained glass windows of Chartres Cathedral.

The enterprising merchants who wrote the Constitution in Philadelphia in the summer of 1787 had it in mind to make their new republic safe for the dream of riches (by the word “liberty,” they meant liberty for property, not persons), and in the pages that follow, it’s no accident that more than a fair share of the commentary is American in attitude and tone. Interpreting the scripture of money is a native art and craft, adapted by the Calvinist clergy in Boston to the blessing of fortunes extracted from the slave trade and the traffic in contraband rum, developed in Benjamin Franklin’s self-help manuals and Alexander Hamilton’s 1790 report to Congress promoting the need for a national bank, further revised and amended over the next 218 years by writers as otherwise unlike one another as Melville, Dreiser, and Fitzgerald into what becomes a national pastime more dearly beloved than baseball.

More than once over the last fifty years in the holy city of New York, I’ve passed the night in the presence of people certain that they were talking about money—about the Federal Funds Rate, the cost of Fifth Avenue apartments, Hillary Clinton’s politics, the prices bid and asked for congressmen in Brooklyn and oranges in Barcelona—and only when the wine is gone and the hostess is no longer speaking to her husband does it become apparent that the banker had been talking about the body of Christ, the lawyer about the doctrine of transubstantiation, the author about her encounter with an apple and a serpent. During the heyday of what was billed as the Reagan Revolution, sometimes as the new American dawn, or “the unfettered free market,” I could discover no common cause among the several degrees of rightist separation (conservative, neoconservative, libertarian, reactionary, and evangelical) other than the moral lesson invariably found in their one and only cautionary tale: money ennobles rich people, making them strong as well as wise; money corrupts poor people, making them greedy as well as weak.

At large in what was still a wilderness west of the Alleghenies in the 1830s, Alexis de Tocqueville, the French politician and essayist commonly regarded as the chief anatomist of the American Commonwealth, noticed that, “In democracies, nothing is greater or more brilliant than commerce. It attracts the attention of the public and fills the imagination of the multitude.” As it was then, so it is now, and from what I can judge by my reading of the country’s history and literature, always has been. Choose any decade in the American house of cards, and commerce is both the hero of the hour and the villain in the play. The two lines of counterpoint provide the basso continuo for the music of the American dialectic, our political disputes resolving into variations on the theme of the argument between different forms of property—free silver and the cross of gold, wage and slave labor, eastern money and western grass, old and new enterprise, large and small capital, Teddy Roosevelt and the trusts, Thomas Jefferson declaring that, “Money, not morality, is the principle of commercial nations,” Abraham Lincoln deploring the proposition that, “One man’s liberty was absolutely nothing when it conflicted with another man’s property,” Daniel Webster asking on behalf of intelligence and industry “only for fair play and an open field,” Woodrow Wilson acknowledging that, “The truth is we are all caught in a great economic system which is heartless.”

Apparently we have a genius for holding in mind innumerable sets of incompatible beliefs, at ease with the assumption that America is most itself when most at odds with itself, when passions of more or less equal weight and intensity balance one another in a unified field of mutual suspicion. Money in the American imagination comes in so many colors, shapes, and hat sizes that it would need a library of Christmas catalogues to list them in alphabetical or preferential order. “Do I contradict myself?” asks Walt Whitman in the Leaves of Grass. “Very well, then I contradict myself / I am large, I contain multitudes.” As in the 1830s, the 1880s, and the 1920s, so again in 2008. The newspapers and the best-selling scribblers of the day cry up money’s glory as the sublime good that buys all other goods—how to make it in four or twelve easy steps, why it is so beautiful, how to groom and cherish it, what to wear in its presence, where it likes to summer in the winter, its comings and goings accompanied by strolling accordions and mafia violins, by Broadway show tunes, fanfares for the common man, hymns scored for gospel choir, full orchestra, and harp. The authors of the country’s literature take a less admiring view. They tend to think of money as a blunt instrument devoid of feeling or compassion. Belonging to the constituency that counts among its members Mark Twain and Henry Adams as well as H.L. Mencken, Zora Neale Hurston, and John Updike, they recognize money as a dull-witted servant notable for its mindless smile, baby-soft and value-free, always happy to help out, content to tune Mozart’s piano or saddle Napoleon’s horse, glad to lend a hand with the brickwork at Auschwitz.

On the question as to whether money is mortal or immortal, the dissonance of contradiction holds as steady as the price of South African diamonds—money denominated in the currencies of divinity or, as Lucius Beebe was fond of saying, in “stuff better suited to the throwing off the back of a moving train”; the path to riches and the road to ruin; public enemy and people’s friend; the passage out and the ticket home; the proof of salvation and the pride that goeth before a fall; Wall Street’s stock market perceived on its upticks as the bearer of Aladdin’s lamp, on its downticks as a den of thieves. No nation donates so much of its capital to the outward expressions of its nonprofit benevolence; no nation spends so much of its income on the shows of opulence advertising inward states of perfection. Awed by the heraldic image of rampant avarice embodied in the figure of Commodore Cornelius Vanderbilt, his fellow railroad operator, Russell Sage, doffs his derby hat and falls devoutly to his Christian knees: “He [Vanderbilt] is to finance what Shakespeare is to poetry and Michelangelo to art.” At more or less the same time in the same Gilded Age, Edith Wharton publishes The House of Mirth, and says of the mise en scène in which the Vanderbilts sometimes consented to walk the earth, “A frivolous society can acquire dramatic significance only through what its frivolity destroys. Its tragic implications lie in its power of debasing people and ideals.”

Andrew Carnegie would have seconded Wharton’s motion. The builders of America’s nineteenth-century industrial colossus, among them John D. Rockefeller and J.P. Morgan, tended to take money less seriously than did their heirs and publicists. As often as not, they were more interested in something else—an idea or a contraption or a problem in geography. Money was a secondary consequence, accumulating in the hall with the flowers, the dachshunds, and the art collection. “The amassing of wealth,” Carnegie regarded as “one of the worst species of idolatry.”

It’s the idolatry that makes the trouble and brings with it the belief in magic. Let men imagine money as something somehow immortal, to be construed as Holy Writ instead of handled as a tool, and they lose both their sense of humor and their capacity to think. The depreciation of any and all values unable to pay a loan shark’s rate of interest transforms the company of gentleman adventurers into a colony of anxious squirrels. Other people come to be seen as objects, commodities, or product placements, and freedom, in practice if not in commencement speeches, as the license to exploit. The American dialectic ceases to flow in an alternating current, and the pathologies of wealth collect in pools of methane gas. The bad air induces mental disorders and breeds “pecuniary standards of culture,” named by Upton Sinclair as those “which estimate the excellence of a man by the amount of other people’s happiness he can possess and destroy.”

The energies began to drain out of the competing systems of American value in the decade of the 1980s, and the country has been suffering the ill effects ever since President Ronald Reagan set up his rose-colored telescope on the White House roof, convinced that, “The difference between an American and any other kind of person is that an American lives in anticipation of the future because he knows it will be a great place.” The Gipper’s revolution brought with it the preferred attitude that the dealers in rainbows seek to instill in the minds of the customers shopping for half-acre lots in the land of milk and honey.

The Money-lender and His Wife, by Quentin Metsys, 1514. Louvre Museum, Paris, France.

For the last twenty-seven years, the news and entertainment media’s relentless booming of the markets in credulity, stimulated by the government’s doping of the banks with injections of access to cheap credit (a policy endorsed by President Clinton and both Presidents Bush), has raised and fattened a large herd of eager converts to the faith in golden calves. What is striking is the degree of their paralysis in the attitudes of holy dread. Never in the history of the world have so many people been so rich; never in the history of the world have so many of those same people felt themselves so poor. They stare into the mirrors of their well-publicized magnificence, the happiest and freest people ever to have seen the light of day, and because they expect from money more than money can supply, they’re disappointed to see a face unlikely to launch a rowboat, much less a thousand ships. They rent the Philadelphia Orchestra and complain that it doesn’t know how to play the music of the spheres. The feasts of voracious consumption testify not to a fullness of appetite but to a failure of the imagination similar to the one experienced by the Phrygian King Midas, who wished that everything he touched be turned to gold. The request was granted, and the king discovered that he couldn’t eat or drink the stuff. He would have starved to death had not Dionysus taken pity on his predicament and released him from the prison of his golden wish.

This second issue of Lapham’s Quarterly presents a plan of escape from the same county jail. Let men employ money as energy made by mortal men for the use of mortal men—as the active and productive wealth underwriting Hamilton’s projections of the public good, in the form of the Medici loans floating the speculation of the Renaissance—and money enlarges the sum of man’s humanity to man. Money gathers its meanings from the uses to which it’s put, and its lesser accomplishments become clear in the pages of yesterday’s newspapers. Who now can remember the deifications of Nicholas Biddle and Robert Vesco? Who can name the ten most powerful men in St. Joseph, Missouri in 1845? When I look at the billionaires smiling down from Olympus on the photographers from Vanity Fair (“The Power Brokers,” “The Men Who Really Count,” etc.), I think of the gentry in fifteenth-century Florence dressed up as saints in the foregrounds of Fra Filippo Lippi’s religious paintings. They gaze at the Madonna with expressions like the one President George W. Bush brings to the television cameras for a press conference at an army or air force base. They have paid for the space, and they expect to be introduced to the best people in heaven.

Over the course of time, it is the power of mind over matter that shapes the clay of civilization. Money follows with the baggage, traveling with the flute players and the dancing bears, bribing the pope, and putting up the tents. It can maintain the status quo, whether of tyranny or democracy; it can employ four hundred thousand automobile workers or Benvenuto Cellini; it can buy Panama or Aristotle Contemplating the Bust of Homer. It is a power worth the having, but without the greater power of thought, it amounts to little more than the temporary dominion of a bully.

The bully is bigger than it was, bigger and harder to see in the massive cloud of metaphor circling the globe at the speed of light. How then identify the perp with a name, age, license number, and last known address? By breaking down the engine into some of its smaller moving parts. Exchange Rates borrows its organizing principle from Marshall McLuhan’s note on money as both a language and a technology translating forms of work into forms of property, the “bridge” of numbers that supports the weight of the world’s desire; Earnings and Expenditures are self-explanatory; Liquidity demonstrates the theorem of Jackson Lears’

essay touching upon money’s function as the buoy that marks the rise and fall of social name and standing in the sea of chance and circumstance; Derivatives points to a few of the consequences—among them the collapse of the Roman Empire and last year’s bursting of the credit bubble—that follow from the rule of money unhedged with positions of reasonable doubt. The five-part improvisation can be read as an attempt to restore power to the American dialectic; it also can be read as a gloss on the bull market in superstition, along the lines of what the watchers at the bedside of the Dow Jones Industrial Average like to call “a technical correction.”