I have always found it in mine own experience an easier matter to devise many and profitable inventions than to dispose of one of them to the good of the author himself.

—Hugh Plat, 1595Prometheus’ Toolbox

Human life as technology from Greek mythology to Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.

By Adrienne Mayor

Prometheus Forms Man and Animates Him with Fire from Heaven, by Hendrik Goltzius, 1589. Rijksmuseum.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

How long have we been imagining artificial life? A remarkable set of ancient Greek myths and art shows that more than 2,500 years ago, people envisioned how one might fabricate automatons and self-moving devices, long before the technology existed. Essentially some of the earliest-ever science fictions, these myths imagined making life through what could be called biotechne, from the Greek words for life (bio) and craft (techne). Stories about the bronze automaton Talos, the artificial woman Pandora, and other animated beings allowed people of antiquity to ponder what awesome results might be achieved if only one possessed divine craftsmanship. One of the most compelling examples of an ancient biotechne myth is Prometheus’ construction of the first humans.

Prometheus was first introduced in Hesiod’s poems, written between 750 and 650 bc, and about two dozen Greek and Latin writers retold and embellished his story. From earliest times Prometheus was seen as the benefactor of primitive humankind. One familiar rendering of the Prometheus myth was featured in the Athenian tragedy Prometheus Bound, attributed to Aeschylus, circa 460 bc. The play opens with the blacksmith god Hephaestus reluctantly chaining Prometheus to a rock at the end of the world. The chorus asks Prometheus why he is being punished. “I gave humans hope,” he replies, “so they may be optimistic, and taught them the secrets of fire, from which they may learn many crafts and arts (technai).”

But fire was the sacred possession of the immortals, and Zeus, the tyrannical king of the gods, took harsh revenge on Prometheus for stealing fire for the benefit of mere mortals, sending an eagle to gnaw eternally at his liver. The technology of fire gave humans some autonomy from their divine creators—now they could invent language, plan cooperatively, make tools, protect themselves from the elements and from each other, and increasingly manipulate the world around them according to their own desires. In time Prometheus’ gifts were expanded to include writing, mathematics, medicine, agriculture, domestication of animals, mining, science—in other words, all the arts of civilization. We might say that by giving men and women this basic technology, Prometheus opened the door for humans—themselves products of divine biotechne—to begin engaging in their own biotechne.

By the fifth century bc, the Athenians were venerating the rebel Prometheus and his precious gifts of fire and technology alongside the city’s favorite gods, Athena and Hephaestus. During the city’s most important civic festival, the Panathenaia, the Fire-Bringer Prometheus was honored with a torch race. Runners began at his altar outside the city walls and wound through the Kerameikos, the district of potters and other craftspeople who revered Prometheus as their patron. The torch race culminated with the last runner kindling the sacred fire on Athena’s altar on the Acropolis.

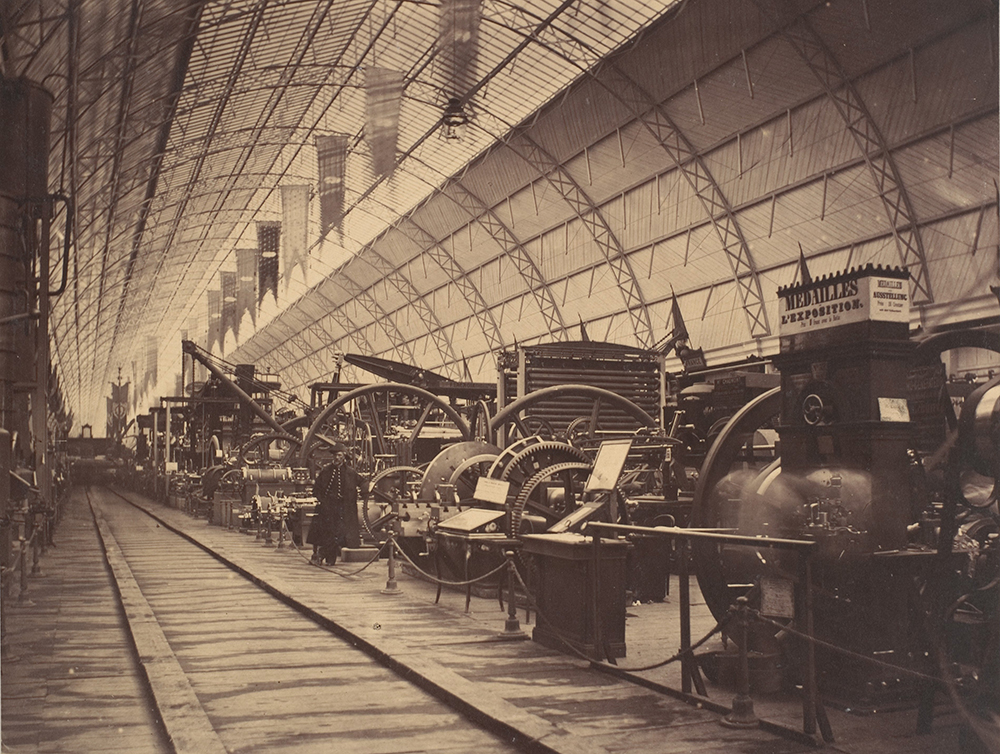

Palace of Industry at the Universal Exposition, Paris, 1855. Photograph by Charles Thurston Thompson. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Horace W. Goldsmith Foundation Gift, through Joyce and Robert Menschel, 1992.

In the Middle Ages and the Renaissance, Prometheus’ theft of fire and his torment by Zeus’ eagle transformed into an allegory for the human soul seeking enlightenment. Ever since antiquity Prometheus has inspired artists, writers, thinkers, and scientists as a symbol of technological creativity and inventive genius as well as humanism, reason, and heroic resistance against tyranny.

Why might Prometheus have risked the anger of the gods to help humans? One possible reason is given in the myth of Prometheus and Epimetheus, related by Plato in the fourth century bc. After earth’s creatures had been created, each was “programmed” with capabilities and defenses so that they would not fall into mutual destruction but could maintain equilibrium in nature. But the animals received all the “apps” first, and nothing was left over for the naked and defenseless humans. Feeling pity, Prometheus gave the puny mortals craft and fire.

Another mythic thread describes Prometheus as the creator of human beings, which offers a more visceral explanation for his concern for vulnerable men and women and his theft of the technology of fire for their benefit. The earliest literary mention of this myth comes from the poet Sappho. In about 600 bc she wrote, “Prometheus is said to have stolen fire after he created mankind.” In this myth, later recounted by Ovid, Gaius Julius Hyginus, and others, the Titan mixed earth and water (or tears) to make the original humans. According to ancient folklore, one could even visit the place where Prometheus accomplished his handiwork, at ancient Panopeus near Chaeronea in central Greece. In the second century, the inquisitive Greek traveler Pausanias found the ruins of Panopeus and marveled at two large boulders in a ravine, each big enough to fill a cart. “They say,” he wrote, “that these are the remains of the clay out of which the whole race of man was fashioned by Prometheus.” Sniffing the boulders, Pausanias declared that the “scent of human skin still clings to the lumps of clay.” (One can only speculate on the source of the odor Pausanias and others claimed to detect.)

Mud willed to life by divine power was a common metaphor in antiquity. In tales from Gilgamesh to Genesis, the creator or demiurge uses mundane materials—earth, clay, mud, dust, bone, water, tears, or blood—to form male and female shapes, which receive the spark of life from gods, wind, fire, or some other force of nature. This archaic mud metaphor would be eclipsed many centuries later, with new understandings of the human body as a mechanistic being driven by dynamic, moving fluids and the invention of mechanical, hydraulic, and pneumatic engineering in the Hellenistic era (c. 323–31 bc).

In typical creation myths, the first human forms were enlivened in what one might call “magic wand” scenarios: life is bestowed on inert objects by a spell or a god’s command. Inanimate objects are brought to life by fiat in the Greek myth of the great flood sent by Zeus. Deucalion and his wife, Pyrrha, the sole survivors, learn from an oracle how to repopulate the earth: they toss stones over their heads, and the stones are instantly transformed into men and women. In Chinese mythology, the goddess of order, Nu Gua, created the first people from droplets of mud flung from a rope. The Old Testament story of Adam shaped from earth is another example of creation by fiat. Magic-wand stories involve no ingenuity, design, or tools, no craft or manufacturing processes, no internal structures or workings; no notions of mechanics are implied. A notable exception is the very ancient Egyptian myth of the divine potter god Khnum (the name means “Builder”), who fabricated the first humans. As early as the Eleventh Dynasty (2130–1991 bc), artists depicted Khnum making human beings using the technology of the potter’s wheel, a machine with a shaft and flywheel perfected in Egypt around 3000 bc.

Written accounts of the myth of Prometheus are full of suggestions that humans were once viewed as artificial creations in the ancient Greek and Roman worlds, but the earliest known illustrations of the Promethean feat are even more intriguing, for the images give the story a surprising technological twist.

The best-known artworks of Prometheus as creator were made during the late Roman Empire. Scenes carved in relief on stone sarcophagi show him molding human figures of clay, guided by the goddess Minerva (Athena), who bestows the spark of life, symbolized by a butterfly. This late Roman imagery appeared in the early Christian era, from the late second through fourth centuries, and emphasized the collaboration of Prometheus and Minerva. First Prometheus forms small male and female dolls or mannequins, who lie inert or stand about awaiting Minerva’s divine touch to spring to life. These Promethean scenes influenced Christian representations of the creation of Adam and Eve, as in the “Dogmatic” sarcophagus relief in the Vatican (c. 350) showing God bringing to life small clay figures of Adam and Eve.

Remarkably, however, about a thousand years before the Roman-Christian images of Prometheus became so popular on coffins, another group of creative artists in Italy took a very different approach to depicting the fabrication of the first human beings. Instead of clay dolls waiting to be brought to life by a goddess, the humans in these works are imagined as products of technology. These striking images appear in a little-known collection of exquisitely engraved gems representing Prometheus as an engineer, using tools to fabricate the protohuman.

Miniature scenes carved on carnelian, amethyst, and other precious gemstones were extremely popular in classical antiquity. The tiny intaglios and cameos were set in personal rings, brooches, amulets, and seals. Starting in the fifth century bc, intricately carved Etruscan and Etruscan-style gems often depicted sculptors or artisans at work, and they illustrated mythic and real craftsmanship in unexpected ways. Etruscan culture, which flourished in Italy several centuries before the rise of Rome, was highly influenced by classical Greek mythology. Etruscan artists are known for interpreting Greek myths in a unique manner on mirrors, vases, and gems. The unusual scenes of Prometheus (called Prumathe in Etruscan) as an engineer of human anatomy appear on about sixty intaglio rings, seals, and scarabs, dating to the fourth to second century bc. Despite their exceptional technological imagery, these gems have attracted scant attention beyond cataloguing and dating.

The artists who carved the gems portray the human prototype (usually male but sometimes female) as incomplete, in the process of being worked with tools and assembled piece by piece on a framework, much as a sculptor would construct a statue upon an internal armature or in sections. In other words, the gems illustrate biotechne rather than magic or fiat in making artificial life.

Pictured as a solitary artisan, Prometheus fabricates the first human in a step-by-step procedure. He employs methods and tools that would have been easily recognizable to real craftsmen in antiquity: hammer, mallet, scraper, scalpel, scaffolding, rods to measure the proportions of the figure, and plumb line and plummet.

The vignettes on the gems fall into two types. In the first, Prometheus is fashioning an unfinished body—head, torso, one arm—supported by ropes on a framework of poles. At least one of these gems includes the foreparts of a horse and a ram, reflecting the ancient tradition that Prometheus was also the creator of the first animals.

The second type is even more extraordinary, for here we see Prometheus working from the inside out. Instead of molding a figure on a metal or wood frame, he starts by building the figure’s natural internal armature, the human skeleton—all the more astonishing because depictions of human skeletons are otherwise almost unknown in ancient Greek art. In these gems Prometheus typically affixes the arm bone to the human skeleton, using a mallet or hammer. The expectation is that he will add internal organs, blood vessels, flesh, skin, hair, and so on—working outward from naturalistic interior anatomy to the finished human prototype.

On one gem, now lost but preserved in an engraving of 1778, a curious scene combines the two types: we see the back of a partially molded male torso on a human skeleton. Prometheus, seated and holding a tool in his right hand, is shown fleshing out the man’s upper back and arms attached to a bare skull and the lower vertebrae, pelvis, and leg bones of the skeleton. The area where the partially fleshed-out ribs meet the skeletal vertebrae is similar to the narrow “unfinished” waist in the other gems depicting the upper half of a man.

The decision of the ancient gem artists to show Prometheus constructing the first human starting with the bone structure likens the Titan to a sculptor who constructs a statue upon a model skeleton. In antiquity sculptors did use skeletal forms, called kanaboi, usually of wood, as the internal core around which they attached clay, wax, or plaster in the first stages of creating statues. Wooden cores were also used with cold-hammered sheets of metal and in the technology of lost-wax casting of bronze statues, as described by Pausanias, Julius Pollux, and others. The process was mentioned by Pliny the Elder, who admired the excellently wrought small clay models and wooden skeletons used in the first stages of making bronze statues in the studio of the renowned sculptor Zenodorus in Rome. Wooden armatures did not survive the heat of casting, but modern analyses of famous ancient bronze statues reveal that metal armatures were also used. A kanabos served as a kind of three-dimensional diagram of body structure. With this methodology in mind, one can appreciate how the scenes on the unusual Etruscan gems imagine Prometheus designing his project, using technology and tools, and starting by assembling a real kanabos, the physical structure of what will become the first human.

In his treatises on biological anatomy and movement—written in the fourth century bc, the time of the Etruscan gems—Aristotle speaks of kanaboi and evokes mechanical dolls, puppets, and other self-moving automatons of his day as analogies to help explain the inner mechanical composition and workings of animals and humans. He compares the way the network of blood vessels “displays the shape of the entire body” to “the wooden skeleton (kanabos) used in artist’s modeling.” Referring to the skeleton as the framework that allows movement, Aristotle’s language is mechanistic; he notes that animals have sinews and bones that function much like the cables attached to pegs or iron rods inside automatons.

In the context of artists imagining a technologically oriented construction of a human form from naturalistic internal anatomy to external features, it is fascinating to compare an ancient Chinese tale of artificial life, in which a lifelike automaton was created from the inside out with functioning internal structures. Set during the reign of King Mu (c. 976–922 bc) of the Zhou dynasty, the story describes an android created by a master “artificer” named Yen Shih. The tale appears in the Liezi, attributed to the Taoist philosopher Lie Yukou. Master Yen brings his marvelous robot to the court of King Mu and his royal concubines. The automaton walks, dances, sings, and otherwise perfectly mimics the actions of a real man. The king is entranced—until the man flirts with one of the concubines. King Mu is enraged, then astounded when Yen opens up the automaton to reveal its biotechnological construction, the “exact replication of human physiology in artificial form (jiawu).” Lifelike down to the finest detail, the outer body is made of leather, wood, glass eyes, real hair and teeth, glue, and lacquer, and inside are artificial muscles and a jointed skeleton, with all the organs—liver, heart, lungs, intestines, spleen, kidneys—each of which controls specific bodily functions.

Modern science fiction continues this ancient theme of building hyperrealistic androids from the inside out. Just as in myths, where immortal gods and goddesses play out their own power games, manipulating, withholding, rewarding, and punishing generations of mortals for eternity, so humankind, as it became more technologically advanced, developed the urge to create and control life, to be like the gods. Many ages ago the vision of capricious gods or careless, even evil, demiurges haphazardly doling out natural capabilities and controlling or neglecting their human toys sketched the outlines of what has become a chilling genre of science fiction.

You cannot endow even the best machine with initiative; the jolliest steamroller will not plant flowers.

—Walter Lippmann, 1913Written in 1816 and published in 1818, Mary Wollstonecraft Shelley’s Frankenstein was strongly shaped by Promethean mythology. The author’s father, William Godwin, had written commentary on Prometheus and other seekers of artificial life in antiquity, and her husband, Percy Bysshe Shelley, and their friend Lord Byron each composed poems about Prometheus. In her novel Mary Shelley conceived of her scientific genius Victor Frankenstein as a Promethean “fire bringer” for her era. She also drew on what were then exciting scientific and pseudoscientific ideas about alchemy, chemistry, electricity, and human physiology.

Other influences include reports of gruesome dissection experiments carried out by the notorious alchemist Johann Dippel of Frankenstein Castle in Germany; Shelley had taken a journey on the Rhine and visited Gernsheim, about ten miles from the castle, in 1814. And debates over the electrostimulation work of Luigi Galvani and others were much in the public eye. Shelley was certainly aware of experiments in which animal and human corpses were grotesquely “reanimated” with electricity. A public demonstration of galvanism on the twitching cadaver of an executed criminal was staged in London in 1803, for example. Not coincidentally, Shelley drew her subtitle The Modern Prometheus in part from the philosopher Immanuel Kant’s famous 1756 essay warning against the overweening “curiosity” exemplified by Benjamin Franklin’s discovery of electricity.

The ancient Etruscan illustrations of Prometheus putting together human body parts and skeletons seem to take on a biotechnical prescience when we read how the young scientist Victor Frankenstein devotes two years of painstaking work to build an intelligent artificial being. He assembles the creature part by part using raw materials from slaughterhouses and medical dissections. Was Shelley familiar with the ancient Promethean images? Some engravings of the gems were first published in 1778. Several of the gems specifically showing Prometheus working on the unfinished torsos and assembling skeletons were included in the vast collection of ancient and neoclassical gems amassed by the eighteenth-century Scottish antiquarian and engraver James Tassie. An illustrated two-volume catalogue of Tassie’s collection was published in 1791. It is plausible that Shelley and her circle could have observed or heard described the ancient artifacts featuring Prometheus assembling an android.

Two Boys with a Bladder, by Joseph Wright of Derby, c. 1770. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Yet another classical influence on Shelley’s Frankenstein could have been the character of the necromancer Erichtho, a witch who haunts battlefields and graveyards, seeking body parts for her spells. Shelley’s father had written about Erichtho, who was described by Dante, Goethe, and the Latin authors Ovid and Lucan. In a grisly scene in Lucan’s Civil War, Erichtho strides across a smoking battleground, seeking a cadaver with intact lungs to resurrect using dead animal parts. As she mutters incantations over her chosen corpse, it jerks back to life convulsively. Lucan describes it moving about “stiff limbed,” presaging the stereotypical walk of zombies, robots, and Frankenstein’s monster. Appalled to be unnaturally summoned back to life, Erichtho’s living dead man ultimately hurls himself onto a burning pyre. Shelley’s monster also vows to incinerate himself on a flaming pyre.

In Shelley’s story, often hailed as the first modern science fiction novel, the scientist hopes to create a humanoid of sublime beauty and soul. But the resulting creature is a sentient monster who wreaks havoc and bitterly resents his existence. Like many ancient myths and popular legends about artificial life achieved through mysterious supertechnology, Shelley’s horror tale is a meditation on the desire to surpass human limits and the perils of scientific overreaching without full knowledge or understanding of the practical and ethical consequences. Some early modern thinkers saw the classical myth of Prometheus’ endless torture by Zeus’ eagle as a symbol of his gnawing doubts about his creation of humankind.

The artistic representations of Prometheus working with sections of the human body and assembling a skeleton tell us that artists and viewers of antiquity understood his creation as analogous to a sculptor beginning with an interior framework to make automatons, which would then become the original living humans. In the first stage, he builds what viewers recognize as their own anatomy, logically assembling the progenitors of the human race from the inside out. But what does it mean to imagine humans as engineered entities?

In all the variants of the Prometheus creation myth and artwork, the realistic forms of humans will become the reality they portray: they become real people. This paradoxical perspective raises the timeless question: Are humans somehow automatons of the gods? The almost subconscious fear that we could be soulless machines manipulated by other powers poses a profound philosophical conundrum pondered since ancient times. If we are the creations of the gods or unknown forces, how can we have self-identity, agency, and free will?

Plato was one of the first to consider the possibility that humans are nonautonomous, writing in Laws, “Let us suppose that each of us living creatures is an ingenious puppet of the gods.” Concerns about autonomy also suffuse traditional tales about robots. In the Hindu Kathasaritsagara (c. 1050), an entire city is populated by silent townspeople and animals, later revealed to be realistic wooden puppets controlled by a solitary man on a throne inside the palace. The notion that humans arose as the automatons or playthings of an imperfect or evil demiurge (along with the ensuing questions of volition and morality) was forcefully articulated in gnosticism, a religious movement of the first through third centuries.

As usual, what we call “progress” is the exchange of one nuisance for another nuisance.

—Havelock Ellis, 1914The French philosopher René Descartes, who was quite familiar with the gear- and spring-powered automatons of his day, embraced the idea that the body is a machine. He even predicted that one day we might need a way to determine whether something was a machine or human. What, he mused, “if there were machines in the image of our bodies and capable of imitating our actions?” He suggested that tests based on flexibility of behavior and linguistic abilities might be able to expose nonhuman things. More than four centuries later, one of the replicants in the 1982 film Blade Runner echoes Descartes’ famous conclusion, “I think, therefore I am.”

Yet the dilemma lingers: the impossibility of devising a Turing test to prove to myself that I am not an android automaton. Contemplating the ancient illustrations of human beings as products of Promethean creation, carved on precious gems more than two millennia ago, is another powerful reminder of the age-old philosophical puzzle of human autonomy. Set against the classical Greek account of Prometheus, the modern tale of Frankenstein’s automaton delivers an especially urgent question and warning today: What do creators owe their creations? Victor Frankenstein was ultimately appalled by his monster and disowned it, while Prometheus is the archetype of a creator who feels a sense of empathy and takes responsibility for his biotechnical creation. As the juggernaut of ever-more advanced technology speeds relentlessly onward, it is perhaps worth recalling that the original Greek meaning of the name Prometheus is “foresight.”