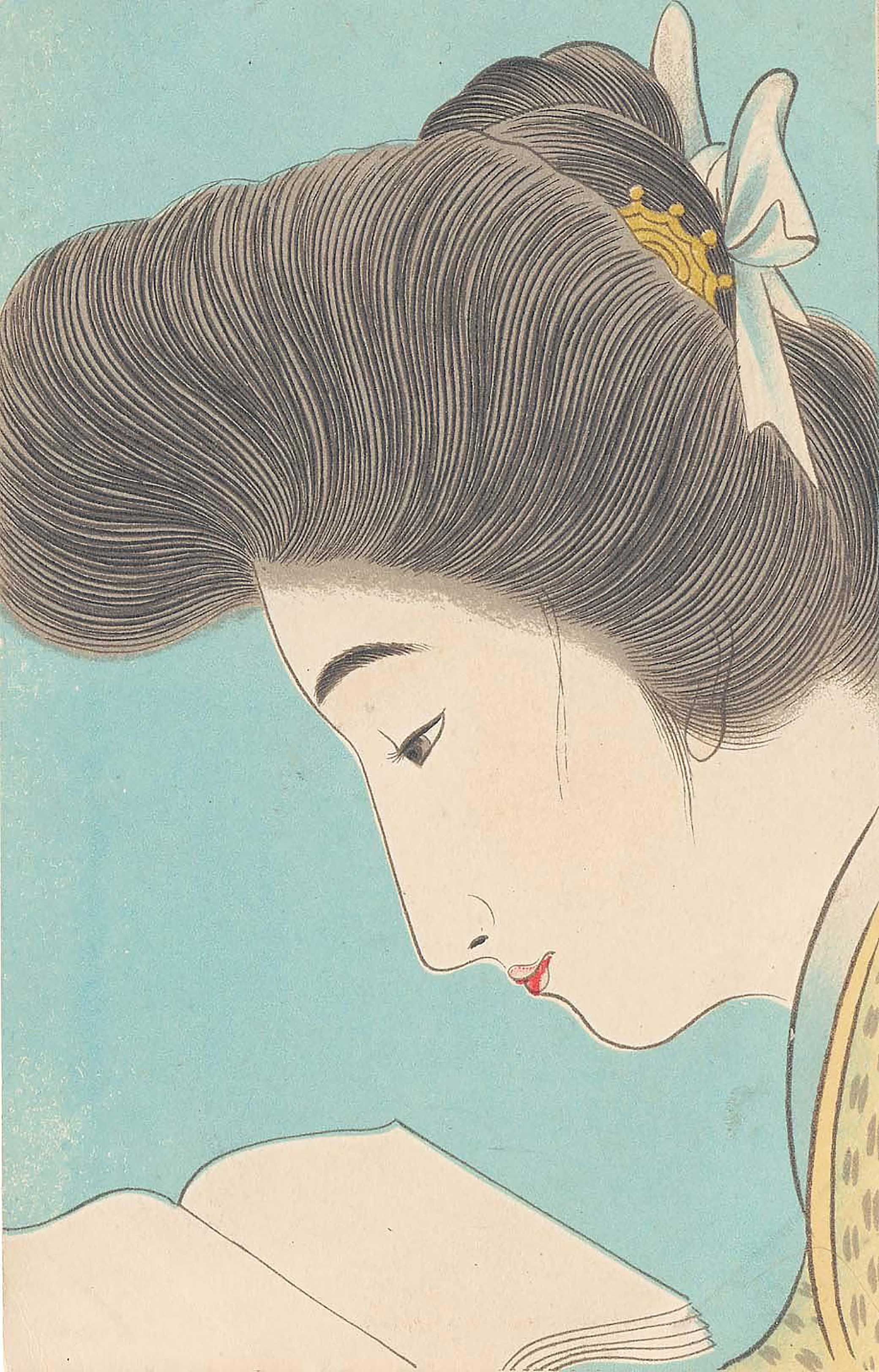

Woman Reading, Japan, late Meiji era. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Japanese Postcards.

For the rest of the year, Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the subject of history and the pleasures, pain, and knowledge that can be found from studying it. For more than fifty issues, contributors from antiquity to the present day have participated in millennia-spanning conversations on themes including friendship, happiness, death, and the future. But what did they make of the idea of studying the past in the first place? Check back every Thursday from now until the end of the year to read the latest.

On January 3, 1868, a peaceful coup took place in Kyoto when a collection of court nobles and select samurai entered the imperial palace and announced the end of the shogun’s rule. Sixteen-year-old Mutsuhito installed himself as the emperor Meiji, and after a brief civil war the Tokugawa shogunate ended. The shogun’s daimyo, or feudal barons, were paid off and their lands divided into prefectures. Over the next forty-five years, the emperor introduced so many reforms that one citizen claimed that it felt like he had been alive for four hundred years.

Six years after the coup, Etsu Inagaki was born to a former daimyo and his wife in the wintry province of Echigo, or “behind the mountains,” a region separated from the rest of Japan by the Kiso mountain range and so remote that the early feudal government had sent offenders into exile there if they were too powerful to imprison. The Meiji restoration had reduced the Inagaki family in status and power and taken away much of their wealth, leaving this samurai family, in their rambling, makeshift house in an old town whose castles had all fallen, somewhat outside of time. Etsu was raised on their traditional roles and customs, their Buddhist and Shinto philosophies, their beliefs in honor and stoicism, and held to these through her brother’s estrangement from her father, her father’s early death, and her brother’s dramatic return to the family. When she was thirteen her mother told her that her “destiny as a bride has been decided,” and Etsu bowed deeply, touching her head to the floor. “The life of a samurai, man or woman, is just the same: loyalty to the overlord; bravery in defense of his honor,” her grandmother told her. “In your distant, destined home, remember…loyalty to your husband; bravery in defense of his honor. It will bring you peace.”

Etsu did not meet Matsuo Sugimoto, a businessman living in Ohio, before they married; all she had at the time of her engagement was his photograph. In preparation for her marriage, she was sent to an English girls’ mission school in Tokyo, where she experienced myriad small culture shocks at the crossroads of “a semi-mythical past and an emergent international present,” and then sailed across the Pacific to join Sugimoto in America. Her story, she said, was a story of “how a daughter of feudal Japan, living hundreds of years in one generation, became a modern American.”

Sometime around 1918, after her husband’s death, Etsu Sugimoto was approached by the journalist and editor Christopher Morley, and asked to contribute anecdotes and memories from her childhood in Japan to his column in the Philadelphia Evening Public Ledger. These stories grew to include her emigration to the United States and observations about her new life and companions, and were later collected in the memoir A Daughter of the Samurai. “This book is history properly told,” Morley wrote in his introduction. “Some of us may think that Mrs. Sugimoto has been even a little too generous toward the America she adopted. But she came among us as Conrad came among the English; and if the little Estu-bo, the well-loved tomboy of snowy winters in Echigo, finds beauty in our strange and violent ways, we can only be grateful.”

In the following scene, which takes place during Etsu’s time at school in Tokyo, she ruminates on the influence of Tennyson, especially his 1864 poem “Enoch Arden,” a story about a man who went missing for eleven years and returned home to find that his wife had assumed he was dead and was now happily married to another man. He decided never to reveal himself in order to protect her and died of a broken heart. Etsu and her peers were enamored of the sense of familial sacrifice that Arden embodies, like a samurai.

Our time in school was supposed to be equally divided between Japanese and English, but since I had been already carefully drilled in Japanese studies, I was able to put my best efforts on English. My knowledge of that language was very limited. I could read and write a little, but my spoken English was scarcely understandable. I had, however, read a number of translations of English books and—more valuable than all else—I possessed a supply of scattered knowledge obtained from a little set of books that my father had brought me from the capital when I was only a child. They were translations, compiled from various sources and published by one of the progressive book houses of Tokyo.

I do not know whose idea it was to translate and publish those ten little paper volumes, but whoever it was holds my lasting gratitude. They brought the first shafts of light that opened to my eager mind the wonders of the Western world, and from them I was led to countless other friends and companions who, in the years since, have brought to me such a wealth of knowledge and happiness that I cannot think what life would have been without them. How well I remember the day they came! Father had gone to Tokyo on one of his “window toward growing days” trips.

That was always an important event in our lives, for he brought back with him not only wonderful stories of his journey but also gifts of strange and beautiful things. Mother had said that he would be home at the close of the day, and I spent the afternoon sitting on the porch step watching the slow-lengthening shadows of the garden trees. I had placed my high wooden clogs on a stepping-stone just at the edge of the longest shadow, and as the sun crept farther I moved them from stone to stone, following the sunshine. I think I must have had a vague feeling that I could thus hasten the slanting shadow into the long straight line which would mean sunset.

At last—at last—and before the shadow had quite straightened, I hurriedly snatched up the clogs and clattered across the stones, for I had heard the jinricksha man’s cry of “Okaeri!” just outside the gate. I could scarcely bear my joy, and I have a bit of guilt in my heart yet when I recall how crookedly I pushed those clogs into the neat box of shelves in the “shoe-off” alcove of the vestibule.

The next moment the men, perspiring and laughing, came trotting up to the door where we, servants and all, were gathered, our heads bowed to the floor, all in a quiver of excitement and delight, but of course everybody gravely saying the proper words of greeting. Then, my duty done, I was caught up in my father’s arms and we went to Honorable Grandmother, who was the only one of the household who might wait in her room for the coming of the master of the house.

That day was one of the “memory stones” of my life, for among all the wonderful and beautiful things which were taken from the willow-wood boxes straddled over the shoulders of the servants was the set of books for me. I can see them now. Ten small volumes of tough Japanese paper, tied together with silk cord and marked Tales of the Western Seas. They held extracts from Peter Parley’s World History, National Reader, Wilson’s Readers, and many short poems and tales from classic authors in English literature.

The charm of delight that rare things give came to me during days and weeks—even months and years—from those books. I can recite whole pages of them now. There was a most interesting story of Christopher Columbus. It was not translated literally, but adapted so that the Japanese mind would readily grasp the thought without being buried in a puzzling mass of strange customs. All facts of the wonderful discovery were stated truthfully, but Columbus was pictured as a fisher lad, and somewhere in the story there figured a lacquer bowl and a pair of chopsticks.

These books had been my inspiration during all my years of childhood, and when, in my study of English at school, my clumsy mind began to grasp the fact that, hidden beneath the puzzling words were continuations of stories I knew, and of ideas similar to those I had found in the old familiar books that I had loved so well, my delight was unbounded. Then I began to read eagerly. I would bend over my desk, hurrying, guessing, skipping whole lines, stumbling along—my dictionary wide open beside me, but I not having time to look—and yet, in some marvelous way, catching ideas. And I never wearied. The fascination was like that of a moon-gazing party, where, while we watched from the hillside platform, a floating cloud would sail across the glorious disk, and we—silent, trembling with excitement—would wait for the glory of the coming moment. In the same way, a half-hidden thought—elusive, tantalizing—would fill me with a breathless hope that the next moment light would come. Another thing about English books was that, as I read, I was constantly discovering shadowy replies to the unanswered questions of my childhood. Oh, English books were a source of deepest joy!

I am afraid that I should not have been so persistent, or so successful in my English studies, could I have readily obtained translations of the books I was so eager to read. Tokyo bookshops, at that time, were beginning to be flooded with translations of English, French, German, and Russian books; and these generally, if not scientific treatises, were classics translated, as a rule, by our best scholars; but they were expensive to purchase and difficult for me to obtain in any other way. To read, even stumblingly, in the original, the books in the school library was my only resource, and it became one of my greatest pleasures.

Excepting English, of all my studies history was the favorite; and I liked and understood best the historical books of the Old Testament. The figurative language was something like Japanese; the old heroes had the same virtues and the same weaknesses of our ancient samurai; the patriarchal form of government was like ours, and the family system based upon it pictured so plainly our own homes that the meaning of many questioned passages was far less puzzling to me than were the explanations of the foreign teachers.

In my study of English literature, it seems odd that, of all the treasures that I gathered, the one which has been most lasting as a vivid picture is that of Tennyson’s “Dora.” Probably this was because of its having been used by a famous Japanese writer as the foundation of a novel called Tanima no Himeyuri—Lily of the Valley. The story of Dora, being a tale of the firstborn of an aristocratic family disinherited because he loved a rustic lass of humble class, and the subsequent tragedy resulting from the difference in training of different social circles, was a tale familiar and understandable to us. It was skillfully handled, the author, with wonderful word pictures, adapting Western life and thought to Japanese conditions.

The Lily of the Valley appeared at just the time when the young mind of Japan, both high and humble, was beginning to seek emancipation from the stoic philosophy, which for centuries had been the core of our well-bred training, and it touched the heart of the public. The book rushed with a storm of popularity all through the land and was read by all classes, and—which was unusual—by both men and women. It is said that Her Imperial Majesty became so interested in reading it that she sat up all one night while her court ladies, sitting silent in the next room, wearily waited.

I think it was my third year in school that a wave of excitement over love stories struck Tokyo. All the schoolgirls were wildly interested. When translations were to be had we passed them from hand to hand through the school; but mostly we had to struggle along in English, picking out love scenes from the novels and poems in our school library. Enoch Arden was our hero. We were familiar with loyalty and sacrifice on the part of a wife, and understood perfectly why Annie should have so long withstood the advances of Philip, but the unselfishness of the faithful Enoch was so rare as to be much appreciated. The hearts of Japanese girls are no different from those of girls of other countries, but for centuries, especially in samurai homes, we had been strictly trained to regard duty, not feeling, as the standard of relations between man and woman. Thus our unguided reading sometimes gave us warped ideas on this unknown subject. The impression I received was that love as pictured in Western books was interesting and pleasant, sometimes beautiful in sacrifice like that of Enoch Arden; but not to be compared in strength, nobility, or loftiness of spirit to the affection of parent for child or the loyalty between lord and vassal.

At a special meeting of the literature society, I was asked to prepare a three-page essay in English, having one of the cardinal virtues for a subject. Recalling that our Bible teacher frequently quoted “God is love,” I felt that there I had a foundation, and so chose as my topic “Love.” I began with the love of the Divine Father, then, under the influence of my late reading, I drifted along, rather vaguely, I fear, on the effect of love on the lives of celebrated characters in history and poetry. But I did not know how to handle so awkward a subject and reached my limit in both knowledge and vocabulary before the three pages were filled. Faithfulness to duty, however, still held firm, and I wrote on, finally concluding with these words: “Love is like a powerful medicine. When properly used it will prove a pleasant tonic, and sometimes may even preserve life; but when misused, it can ruin nations, as seen in the lives of Cleopatra and the beloved empress of the emperor Genso of Great China.”

At the close of my reading one teacher remarked, “This is almost desecration.”

It was years before I understood what the criticism meant.

Read the other entries in this series: Polybius, Michel de Montaigne, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hardy, Voltaire, Charles Lamb, al-Biruni, Ibn Khaldun, Germaine de Staël, and Agnes Strickland and Elizabeth Strickland.