Neighborly Gossip, by Bernardus Johannes Blommers, c. 1880. Rijksmuseum.

For the rest of the year, Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the subject of history and the pleasures, pain, and knowledge that can be found from studying it. For more than fifty issues, contributors from antiquity to the present day have participated in millennia-spanning conversations on themes including friendship, happiness, death, and the future. But what did they make of the idea of studying the past in the first place? Check back every Thursday from now until the end of the year to read the latest.

“My reading has been lamentably desultory and immethodical,” Charles Lamb writes in “The Old and the New Schoolmaster,” published in London Magazine in May 1821. He goes on to list his various educational weaknesses; when it comes to history, he possesses

some vague points, such as one cannot help picking up in the course of miscellaneous study; but I never deliberately sat down to a chronicle, even of my own country. I have most dim apprehensions of the four great monarchies; and sometimes the Assyrian, sometimes the Persian, floats as first in my fancy. I make the widest conjectures concerning Egypt, and her shepherd kings.

Since this litany of deficiencies was written under his alter ego byline, Elia, which Clare Bucknell notes is “a dramatic personality both appealingly familiar and, for those who stopped to look closely, curiously illegible,” it is hard to fasten this personal history too snugly to Lamb, who seemed to enjoy a good history, as long as it was a bit comfy and didn’t stint on the action.

On March 1, 1800, he wrote to his friend Thomas Manning to recommend several books. One suggestion was Original Letters, Etc. of Sir John Falstaff and His Friends, the only published work of James White, who was so obsessed with Shakespeare’s Falstaff that he often dressed like him and did frequent impersonations for his friends, who called him Sir John. (Lamb was apparently responsible for introducing White to Henry IV.) An 1872 review of the book in The Atlantic was lukewarm, noting that “there is nothing quite fitting for quotation in these letters,” but “as at the best they are only imitations they may pass.” Lamb also recommended Scottish philosopher Gilbert Burnet’s History of His Own Time, a firsthand account of the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution, ending with the reign of Queen Anne. In explaining what he admires about Burnet’s history, he makes clear what he doesn’t like about other, better remembered works. In order to impress Lamb, historians should include plenty of gossip and political subjectivity and not bother too much with philosophy or making the words too pretty.

I hope by this time you are prepared to say the “Falstaff’s Letters” are a bundle of the sharpest, queerest, profoundest humors of any these juice-drained latter times have spawned. I should have advertised you that the meaning is frequently hard to be got at, and so are the future guineas that now lie ripening and aurifying in the womb of some undiscovered Potosí; but dig, dig, dig, dig, Manning! I set to with an unconquerable propulsion to write, with a lamentable want of what to write. My private goings-on are orderly as the movements of the spheres, and stale as their music to angels’ ears. Public affairs, except as they touch upon me, and so turn into private, I cannot whip up my mind to feel any interest in, I grieve, indeed, that War and Nature and Mr. Pitt, that hangs up in [poet Charles] Lloyd’s best parlor, should have conspired to call up three necessaries, simple commoners as our fathers knew them, into the upper house of luxuries—bread and beer and coals, Manning. But as to France and Frenchmen, and the Abbé Siéyès and his constitutions, I cannot make these present times present to me. I read histories of the past, and I live in them; although, to abstract senses, they are far less momentous than the noises which keep Europe awake.

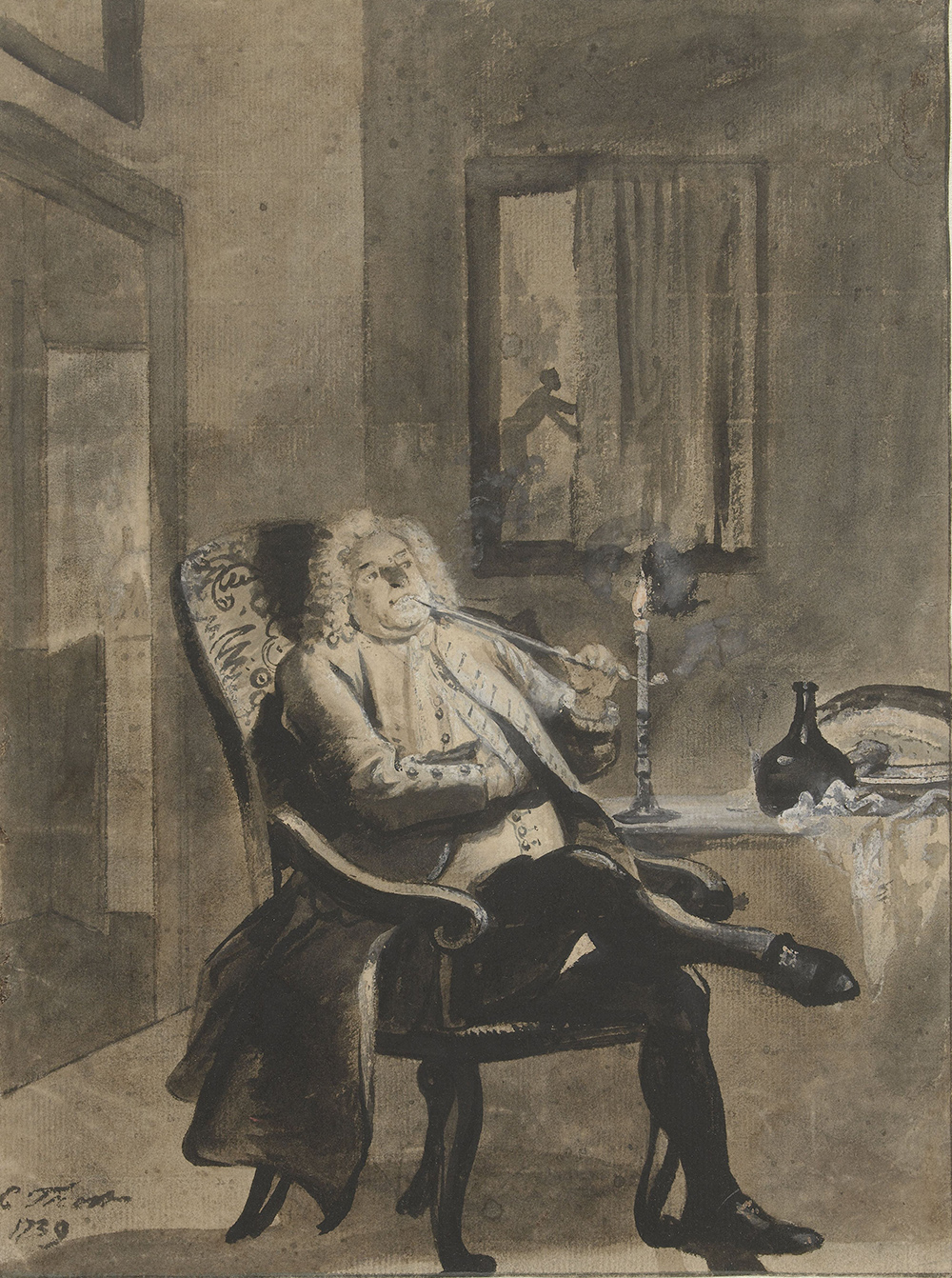

I am reading Burnet’s Own Times. Did you ever read that garrulous, pleasant history? He tells his story like an old man, past political service, bragging to his sons on winter evenings of the part he took in public transactions when “his old cap was new.” Full of scandal, which all true history is. No palliatives; but all the stark wickedness that actually gives the momentum to national actors. Quite the prattle of age and outlived importance. Truth and sincerity staring out upon you perpetually in alto-relievo. Himself a party man, he makes you a party man. None of the cursed philosophical Humeian indifference, so cold and unnatural and inhuman! None of the cursed Gibbonian fine writing, so fine and composite. None of Dr. Robertson’s periods with three members. None of Mr. Roscoe’s sage remarks, all so apposite, and coming in so clever, lest the reader should have had the trouble of drawing an inference. Burnet’s good old prattle I can bring present to my mind; I can make the revolution present to me; the French Revolution, by a converse perversity in my nature, I fling as far from me.

To quit this tiresome subject, and to relieve you from two or three dismal yawns, which I hear in spirit, I here conclude my more than commonly obtuse letter—dull up to the dullness of a Dutch commentator on Shakespeare.

My love to Lloyd and Sophia.

C.L.

Read the other entries in this series: Polybius, Michel de Montaigne, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hardy, Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto, Voltaire, al-Biruni, Ibn Khaldun, Germaine de Staël, and Agnes Strickland and Elizabeth Strickland.