Pen box (qalamdan) depicting Ismail I in a battle against the Uzbeks, nineteenth century, Iran. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, purchase, Elizabeth S. Ettinghausen gift, in memory of Richard Ettinghausen; and Stephenson Family Foundation gift, 2006.

For the rest of the year, Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the subject of history and the pleasures, pain, and knowledge that can be found from studying it. For more than fifty issues, contributors from antiquity to the present day have participated in millennia-spanning conversations on themes including friendship, happiness, death, and the future. But what did they make of the idea of studying the past in the first place? Check back every Thursday from now until the end of the year to read the latest.

Al-Biruni was born in the Khwarazm region of central Asia, along the Aral Sea, in the late tenth century. The Abbasid caliphate in Baghdad had begun to decline, and new states were forming out of its ruins. Khwarazm was known for its advanced culture and science, its palaces and mosques, and its superior religious colleges. The renowned mathematician Abu Nasr Mansur, a prince of the royal family overseeing the region, met the teenage al-Biruni around 990 and took him on as a protégé, teaching him Euclidean geometry and the astronomy of Ptolemy. But a few years later, following the disturbance of new city-states coming to power, the royal family was overthrown in a coup, and the ensuing civil war forced al-Biruni to flee the region. In later years he wrote, “I was permitted by the Lord of Time to go back home, but I was compelled to participate in worldly affairs, which excited the envy of fools, but which made the wise pity me.” He was less interested in politics than in the study of the universe (around the time he returned home he began a correspondence with the young philosopher Avicenna, discussing gravity, the atom, and Aristotle’s Physics), but he was forced to work for royal patrons in Bukhara and elsewhere to support himself.

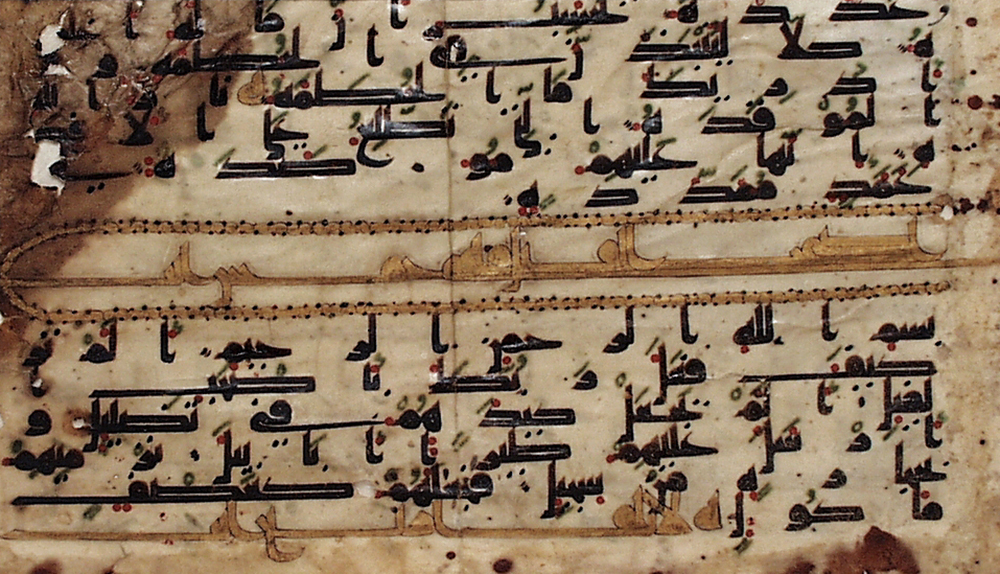

By the time he was twenty-seven, al-Biruni had completed his Chronology of Ancient Nations, in which he aimed “to establish as accurately as possible the time span of various eras,” starting from the very beginning of the human race. He explored every calendar system humanity had used, tracing not only military and political history, as historians of his time often did, but also the customs and morals of the people of every era. In his preface, he writes that he began this book when a scholar he admired asked him to explain the root of the differences in how different cultures marked time. “I was quite aware that this was a difficult task to handle,” he writes, but “I was encouraged by that robe of blessed service in which I have dressed myself”—the garment of the historian. The “best and nearest way” to answering the scholar’s question, he writes,

is the knowledge of the history and tradition of former nations and generations, because the greatest part of it consists of matters that have come down from them, and of remains of their customs and institutes. And this object cannot be obtained by way of ratiocination with philosophical notions…but solely by adopting the information of those who have a written tradition and of the members of the different religions…We must compare their traditions and opinions among themselves when we try to establish our system. But ere that we must clear our mind from all those accidental circumstances that deprave most men, from all causes that are liable to make people blind against the truth.

He writes that for historians the truth “might seem to be almost unattainable—on account of the numerous lies that are mixed up with all historical records and traditions. And those lies do not all on the face of it appear to be impossibilities, so that they might be easily distinguished and eliminated.” Only experience and dedicated study can mitigate the risk of allowing false records to pass for truths. “The life of man is not sufficient to learn thoroughly the traditions of one of the many nations,” he continues, but it is the historian’s duty “to gather the traditions from those who have reported them, to correct them as much as possible, and to leave the rest as it is, in order to make our work help him, who seeks truth and loves wisdom.” Believing as he did in God’s divine plan for history, al-Biruni may have considered writing or failing to correct a false record a kind of desecration.

For his history of Hinduism, Verifying All That the Indians Recount, the Reasonable and the Unreasonable, al-Biruni learned Sanskrit and was likely the first Muslim to study the Puranas. Scholars have noted his rigorous methodology and admirable objectivity in laying out a detailed history, using primary sources whenever possible. “It is the method of our author not to speak for himself but to let the Hindus speak,” wrote his translator Edward Sachau in 1888. “He presents a picture of Indian civilization as painted by the Hindus themselves.” In the preface to his history of India, al-Biruni returns to the importance of truthfulness in written works, because these sources are what go on to build the historical record.

No one will deny that in questions of historic authenticity hearsay does not equal eyewitness; for in the latter, the eye of the observer apprehends the substance of that which is observed, both in the time when and in the place where it exists, while hearsay has its peculiar drawbacks. But for these it would even be preferable to eyewitness; for the object of eyewitness can only be actual momentary existence, while hearsay comprehends alike the present, the past, and the future, so as to apply in a certain sense both to that which is and to that which is not (i.e., which either has ceased to exist or has not yet come into existence). Written tradition is one of the species of hearsay—we might almost say the most preferable. How could we know the history of nations but for the everlasting monuments of the pen?

The tradition regarding an event that in itself does not contradict either logical or physical laws will invariably depend for its character as true or false upon the character of the reporters, who are influenced by the divergence of interests and all kinds of animosities and antipathies between the various nations. We must distinguish different classes of reporters.

One of them tells a lie, intending to further an interest of his own either by lauding his family or nation because he is one of them or by attacking the family or nation on the opposite side, thinking that thereby he can gain his ends. In both cases he acts from motives of objectionable cupidity and animosity.

Another one tells a lie regarding a class of people whom he likes, being under obligations to them, or whom he hates because something disagreeable has happened between them. Such a reporter is near akin to the first mentioned one, as he, too, acts from motives of personal predilection and enmity.

Another tells a lie because he is of such a base nature as to aim thereby at some profit, or because he is such a coward as to be afraid of telling the truth.

Another tells a lie because it is his nature to lie, and he cannot do otherwise, which proceeds from the essential meanness of his character and the depravity of his innermost being.

Lastly, a man may tell a lie from ignorance, blindly following others who told him.

If reporters of this kind become so numerous as to represent a certain body of tradition, or if in the course of time they even come to form a consecutive series of communities or nations, both the first reporter and his followers form the connecting links between the hearer and the inventor of the lie; and if the connecting links are eliminated, there remains the originator of the story, one of the various kinds of liars we have enumerated, as the only person with whom we have to deal.

That man only is praiseworthy who shrinks from a lie and always adheres to the truth, enjoying credit even among liars, not to mention others.

It has been said in the Quran, “Speak the truth, even if it were against yourselves”; and the Messiah expresses himself in the Gospel to this effect: “Do not mind the fury of kings in speaking the truth before them. They only possess your body, but they have no power over your soul.” In these words the Messiah orders us to exercise moral courage. For what the crowd calls courage—bravely dashing into the fight or plunging into an abyss of destruction—is only a species of courage, while the genus, far above all species, is to scorn death, whether by word or deed.

Now as justice (i.e., being just) is a quality liked and coveted for its own self, for its intrinsic beauty, the same applies to truthfulness, except perhaps in the case of such people as never tasted how sweet it is or know the truth but deliberately shun it, like a notorious liar who once was asked if he had ever spoken the truth and gave the answer, “If I were not afraid to speak the truth, I should say no.” A liar will avoid the path of justice; he will, as matter of preference, side with oppression and false witness, breach of confidence, fraudulent appropriation of the wealth of others, theft, and all the vices that serve to ruin the world and mankind.

When I once called upon the master Abu-Sahl Abd-Almunim Ibn Ali Ibn Nuh At-tiflisi, may God Muslim strengthen him! I found that he blamed the tendency of the author of a book on the Mutazilah sect to misrepresent their theory. For, according to them, God is omniscient of himself, and this dogma that author had expressed in such a way as to say that God has no knowledge (like the knowledge of man), thereby misleading uneducated people to imagine that, according to the Mutazilites, God is ignorant. Praise be to God, who is far above such and similar unworthy descriptions! Thereupon I pointed out to the master that precisely the same method is much in fashion among those who undertake the task of giving an account of religious and philosophical systems from which they slightly differ or to which they are entirely opposed. Such misrepresentation is easily detected in a report about dogmas comprehended within the frame of one single religion, because they are closely related and blended with each other.

On the other hand, you would have great difficulty in detecting it in a report about entirely foreign systems of thought totally differing both in principle and details, for such a research is rather an out-of-the-way one, and there are few means of arriving at a thorough comprehension of it. The same tendency prevails throughout our whole literature on philosophical and religious sects. If such an author is not alive to the requirements of a strictly scientific method, he will procure some superficial information that will satisfy neither the adherents of the doctrine in question nor those who really know it. In such a case, if he is an honest character, he will simply retract and feel ashamed; but if he is so base as not to give due honor to truth, he will persist in litigious wrangling for his own original standing point. If, on the contrary, an author has the right method, he will do his utmost to deduce the tenets of a sect from their legendary lore, things that people tell him, pleasant enough to listen to but that he would never dream of taking for true or believing.

Read the other entries in this series: Polybius, Michel de Montaigne, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hardy, Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto, Voltaire, Charles Lamb, Ibn Khaldun, Germaine de Staël, and Agnes Strickland and Elizabeth Strickland.