Basin with figural imagery, Iran, early fourteenth century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Edward C. Moore Collection, bequest of Edward C. Moore, 1891.

For the rest of the year, Lapham’s Quarterly is running a series on the subject of history and the pleasures, pain, and knowledge that can be found from studying it. For more than fifty issues, contributors from antiquity to the present day have participated in millennia-spanning conversations on themes including friendship, happiness, death, and the future. But what did they make of the idea of studying the past in the first place? Check back every Thursday from now until the end of the year to read the latest.

In 1348 the Black Death came to Tunis, possibly from Sicilian ships transporting grain across the Mediterranean. Ibn Khaldun was living in the city with his parents, studying theology, philosophy, Islamic law, and poetry. Over the next two years the plague killed his mother and father and most of Tunis’ scholars. With his life in upheaval and finding it difficult to focus on his studies, Ibn Khaldun, only seventeen years old, decided to pursue a political career. Family tradition also may have inspired him to choose politics over scholarship; many of his male ancestors held prestigious administrative posts in Seville before it was conquered by Spanish Christians. For the next twenty-five years Ibn Khaldun moved between the major cities of Muslim North Africa and Spain, including Fez, Bejaïa, Tlemcen, and Granada, shifting his allegiances frequently as North Africa’s many dynastic rulers vied for power. During this period he married at least one woman and had several children, none of whom he mentions by name in his writings.

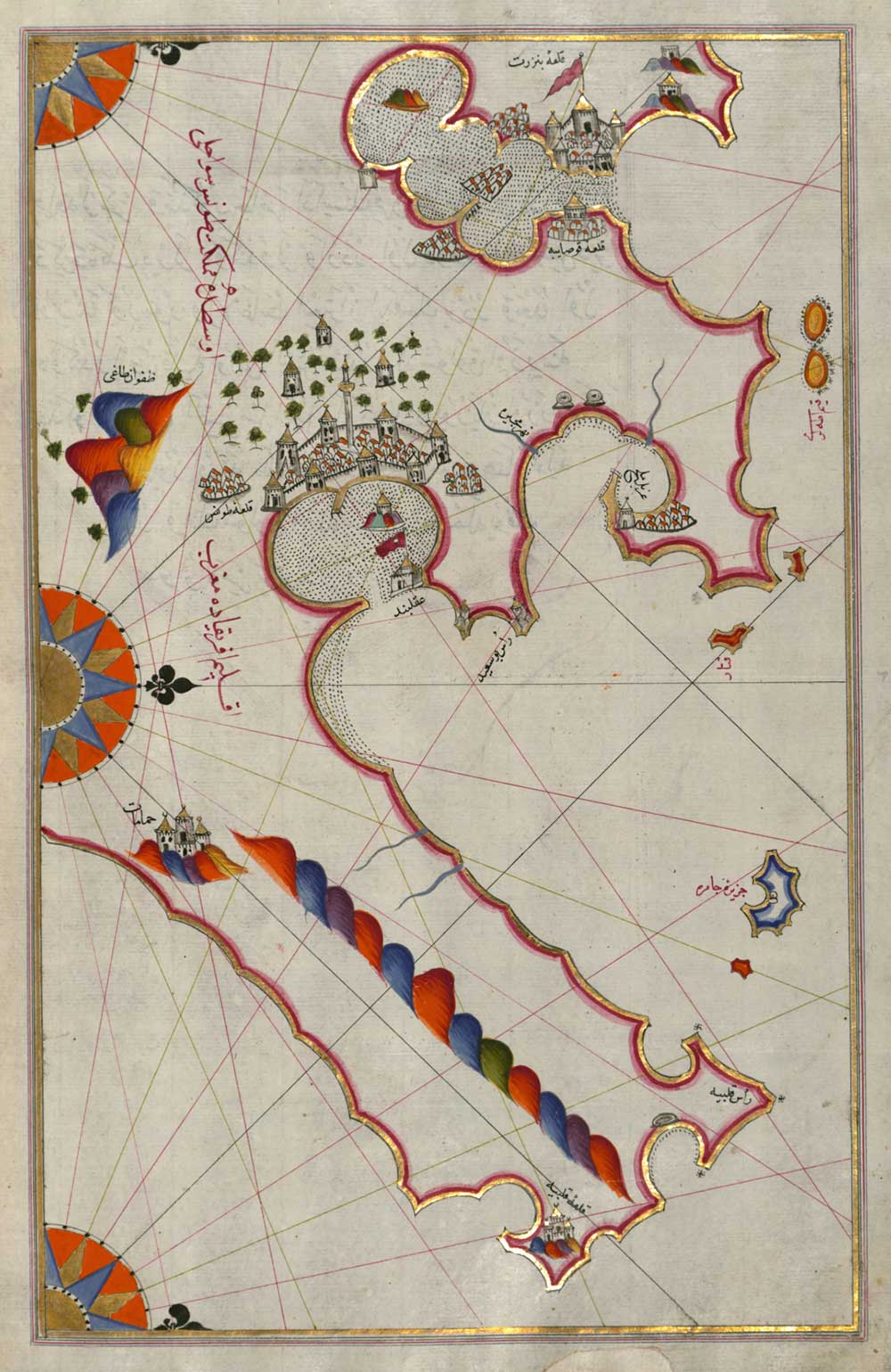

Ibn Khaldun worked successively as a secretary, a diplomat, and an appellate judge and acquired significant political influence by negotiating alliances with several Berber and Arab tribes. However, his inconsistent loyalties and success in rallying the tribes against rulers he opposed made him a political liability. By 1375 he was out of favor with nearly every sultan in the Maghreb. He sought protection from the Awlad Arif tribe, which permitted him and his wife and children to live in the mountaintop fortress of Qalat ibn Salama, in what is today western Algeria. With little to do or read, Ibn Khaldun began to write a historical study of North Africa’s Berber and Arab tribes while watching the Arif tend their flocks. The work expanded into two separate projects: the Muqaddimah (meaning “introduction” in Arabic), an examination of how to study history, and the Kitab al-Ibar, a history of Muslim North Africa.

For Ibn Khaldun, writing history was not a task to be taken lightly. He felt that there were already too many scholarly books circulating among the fourteenth-century Islamic elite, which was “harmful to the human quest for knowledge and to the attainment of a thorough scholarship.” But someone needed to account for how the Black Death had disrupted and reshaped human history during his lifetime, as he explains in this passage from the Muqaddimah, translated by Franz Rosenthal:

Civilization decreased with the decrease of mankind. Cities and buildings were laid waste, roads and way signs were obliterated, settlements and mansions became empty, dynasties and tribes grew weak. The entire inhabited world changed…When there is a general change of conditions, it is as if the entire creation had changed and the whole world been altered, as if it were a new and repeated creation, a world brought into existence anew. Therefore, there is need at this time that someone should systematically set down the situation of the world among all regions and races, as well as the customs and sectarian beliefs that have changed for their adherents, doing for this age what al-Masudi did for his.

Ibn Khaldun acknowledged that al-Masudi was the leading Islamic historian of the era—even calling him the “imam of historians”—but early in the Muqaddimah he established why he wouldn’t be replicating al-Masudi’s approach to history. Al-Masudi deployed historical anecdotes to surprise and entertain his readers, while Ibn Khaldun believed that history should “be accounted a branch of philosophy,” which requires “the causes and origins of existing things and deep knowledge of the how and why of events.” Before setting out his principles of human social organization, he considers how aspiring historians can “get at the truth” in this excerpt from Reynold A. Nicholson’s abridged 1922 translation of the Muqaddimah.

Know that the science of history is noble in its conception, abounding in instruction, and exalted in its aim. It acquaints us with the characteristics of the ancient peoples, the ways of life followed by the prophets, and the dynasties and government of kings, so that those who wish may draw valuable lessons for their guidance in religious and worldly affairs.

The student of history, however, requires numerous sources of information and a great variety of knowledge; he must consider well and examine carefully in order to arrive at the truth and avoid errors and pitfalls. If he relies on bare tradition, without having thoroughly grasped the principles of common experience, the institutes of government, the nature of civilization, and the circumstances of human society, and without judging what is past and invisible by the light of what is present before his eyes, then he will often be in danger of stumbling and slipping and losing the right road.

Many errors committed by historians, commentators, and leading traditionalists in their narrative of events have been caused by their reliance on mere tradition, which they have accepted without regard to its intrinsic worth, neglecting to refer it to its general principles, judge it by its analogies, and test it by the standard of wisdom, knowledge of the natures of things, and exact historical criticism. Thus they have gone astray from the truth and wandered in the desert of imagination and error. Especially is this the case in computing sums of money and numbers of troops, when such matters occur in their narratives; for here falsehood and exaggeration are to be expected, and one must always refer to general principles and submit to the rules of probability.

For example, al-Masudi and many other historians relate that Moses—on whom be peace—numbered the armies of the Israelites in the wilderness after he had reviewed all the men capable of bearing arms who were twenty years old or above that age, and that they amounted to 600,000 or more. Now, in making this statement he forgot to consider whether Egypt and Syria are large enough to support armies of that size, for it is a fact attested by well-known custom and familiar experience that every kingdom keeps for its defense only such a force as it can maintain and furnish with rations and pay. Moreover, it would be impossible for armies so huge to march against each other or fight, because the territory is too limited in extent to allow of it, and because, when drawn up in ranks, they would cover a space twice or three times as far as the eye can reach, if not more. How should these two hosts engage in battle, or one of them gain the victory, when neither wing knows anything of what is happening on the other? The present time bears witness to the truth of my observations: water is not so like to water as the future to the past.

That being so, the rule for distinguishing the true from the false in history is based on possibility or impossibility; that is to say, we must examine human society, by which I mean civilization, and discriminate between the characteristics essential to it and inherent in its nature and those which are accidental and unimportant, recognizing further those which cannot possibly belong to it. If we do that, we shall have a canon for separating historical fact and truth from error and falsehood by a method of proof that admits of no doubt; and then, if we hear an account of any of the things that happen in civilized society, we shall know how to distinguish what we judge to be worthy of acceptance from what we judge to be spurious, having in our hands an infallible criterion that enables historians to verify whatever they relate.

Such is the purpose of the present work. And it would seem that this is an independent science. For it has a subject, namely, human civilization and society, and problems, namely, to explain in succession the accidental features and essential characters of civilization. This is the case with every science, the intellectual as well as those founded on authority.

The matter of the following discourse is novel, original, and instructive. I have discovered it by dint of deep thought and research. It appertains not to the science of oratory, which is only concerned with such language as will convince the multitude and be useful for winning them over to an opinion or persuading them to reject the same. Nor, again, does it form part of the science of civil government, i.e., the proper regulation of a household or city in accordance with moral and philosophical laws in order that the people may be led to live in a way that tends to preserve and perpetuate the species. These two sciences may resemble it, but its subject differs from theirs. It appears to be a new invention; indeed, I have not met with a discourse upon it by anyone in the world. I do not know whether this is due to their neglect of the topic—and we need not think the worse of them for that—or whether, perhaps, they may have treated it exhaustively in books that have not come down to us. Among the races of mankind the sciences are many and the savants numerous, and the knowledge we have lost is greater in amount than all that has reached us.

Read the other entries in this series: Polybius, Michel de Montaigne, Niccolò Machiavelli, Thomas Hardy, Etsu Inagaki Sugimoto, Voltaire, Charles Lamb, al-Biruni, Germaine de Staël, and Agnes Strickland and Elizabeth Strickland.