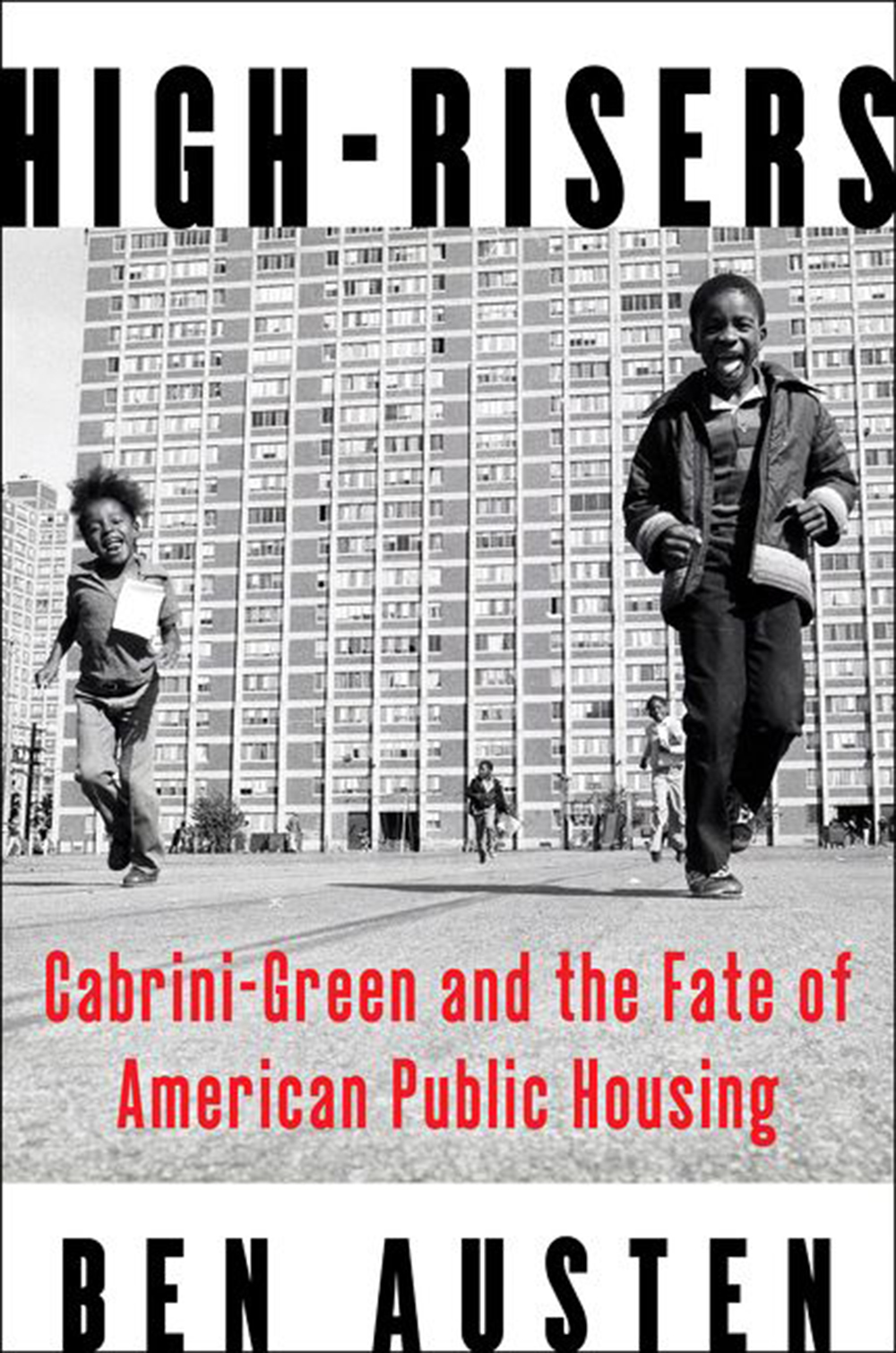

Cabrini-Green Homes. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

Each issue of Lapham’s Quarterly, celebrating its tenth anniversary this year, addresses a theme—States of War, States of Mind, Food, Youth, Animals—by drawing on primary sources throughout history, finding the rhymes and dissonances in how these topics have played out and been perceived over the centuries. In this new series, we open up the sleuthing beyond our staff and four annual themes by letting historians and writers share what they have come across in their recent visits to the archives.

This week’s selection comes from Ben Austen, author of High-Risers: Cabrini-Green and the Fate of American Public Housing, now available from HarperCollins.

Helen, the protagonist of the 1992 horror film Candyman, is a white graduate student researching urban legends. She is looking into the myth of a hook-handed apparition rumored to keep a lair inside Chicago’s most infamous public housing complex, Cabrini-Green. Candyman appears Bloody Mary–style when his name is uttered five times. But the movie itself seems to emerge from that moment’s collective fears—from the constant handwringing over a coming tide of “crack babies,” of “wilding” teens, of “super-predators.” By the 1990s, many center cities were beginning to revive from their postindustrial swoons, and Chicago’s population ticked up for the first time in forty years. For newcomers to the city—the era’s yuppies—urban dangers and devastations were being imagined as near-misses, a wrong turn away. That’s how horror works. It requires that stories of menace flood the blank spaces of the mind. Candyman is the embodiment of public housing itself as the threat.

Helen ventures into the towers of Cabrini-Green. In one of the movie’s most frightening scenes, she enters (alone, of course) what’s conveyed as the ultimate urban nightmare—a men’s public toilet at a giant inner-city housing project. She is attacked not by Candyman but by a group of young men who are appropriating the myth. Later in the film, she learns that her condo building a few blocks away was originally part of Cabrini-Green. It’s an absurdity that taps into the greater dread that nowhere in the city is one safe from this blight. The projects are coming from inside the house.