Old Man

What are the materials of which a steam engine is made?

Young Man

Iron, steel, brass, white metal, and so on.

Old Man

Where are these found?

Young Man

In the rocks.

Old Man

You could make the engine out of the rocks themselves?

Young Man

Yes, a brittle one and not valuable.

Old Man

You would not require much of such an engine as that?

Young Man

No—substantially nothing.

Old Man

To make a fine and capable engine how would you proceed?

Young Man

Drive tunnels and shafts into the hills; blast out the iron ore; crush it, smelt it, reduce it to pig iron; put some of it through the Bessemer process and make steel of it. Mine and treat and combine the several metals of which brass is made.

Chiron and Achilles depicted in a fresco in Herculaneum, Italy, first century. National Archaeological Museum, Naples, Italy.

Old Man

Then?

Young Man

Out of the perfected result, build the fine engine.

Old Man

You would require much of this one?

Young Man

Oh, indeed yes.

Old Man

It could drive lathes, drills, planers, punches, polishers—in a word, all the cunning machines of a great factory?

Young Man

It could.

Old Man

What could the stone engine do?

Young Man

Drive a sewing machine, possibly—nothing more, perhaps.

Old Man

Men would admire the other engine and rapturously praise it?

Young Man

Yes.

Old Man

But not the stone one?

Young Man

No.

Old Man

The merits of the metal machine would be far above those of the stone one?

Young Man

Of course.

Old Man

Personal merits?

Young Man

Personal merits? How do you mean?

Old Man

It would be personally entitled to the credit of its own performance?

Young Man

The engine? Certainly not.

Old Man

Why not?

Young Man

Because its performance is not personal. It is a result of the law of its construction. It is not a merit that it does the things which it is set to do—it can’t help doing them.

Old Man

And it is not a personal demerit in the stone machine that it does so little?

Young Man

Certainly not. It does no more and no less than the law of its make permits and compels it to do. There is nothing personal about it; it cannot choose. In this process of “working up to the matter” is it your idea to work up to the proposition that a man and a machine are about the same thing, and that there is no personal merit in the performance of either?

Old Man

Yes—but do not be offended; I am meaning no offense. What makes the grand difference between the stone engine and the steel one? Shall we call it training, education? Shall we call the stone engine a savage and the steel one a civilized man? The original rock contained the stuff of which the steel one was built—but along with it a lot of sulfur and stone and other obstructing inborn heredities brought down from the old geologic ages—prejudices, let us call them. Prejudices which nothing within the rock itself had either power to remove or any desire to remove. Prejudices which must be removed by outside influences or not at all. The iron’s prejudice against ridding itself of the cumbering rock. To make it more exact, the iron’s absolute indifference as to whether the rock be removed or not. Then comes the outside influence and grinds the rock to powder and sets the ore free. The iron in the ore is still captive. An outside influence smelts it free of the clogging ore. The iron is emancipated iron now, but indifferent to further progress. An outside influence beguiles it into the Bessemer furnace and refines it into steel of the first quality. It is educated now—its training is complete. And it has reached its limit. By no possible process can it be educated into gold. There are gold men, and tin men, and copper men, and leaden men, and steel men, and so on—and each has the limitations of his nature, his heredities, his training, and his environment. You can build engines out of each of these metals, and they will all perform, but you must not require the weak ones to do equal work with the stronger ones. In each case, to get the best results you must free the metal from its obstructing prejudicial ores by education—smelting, refining, and so forth.

Young Man

You have arrived at man now?

Old Man

Yes. Man the machine—man the impersonal engine. Whatsoever a man is, is due to his make and to the influences brought to bear upon it by his heredities, his habitat, his associations. He is moved, directed, commanded by exterior influences—solely. He originates nothing himself—not even an opinion, not even a thought.

Young Man

Oh, come! Where did I get my opinion that this which you are talking is all foolishness?

Old Man

It is a quite natural opinion—indeed an inevitable opinion—but you did not create the materials out of which it is formed. They are odds and ends of thoughts, impressions, feelings, gathered unconsciously from a thousand books, a thousand conversations, and from streams of thought and feeling which have flowed down into your heart and brain out of the hearts and brains of ten centuries of ancestors. Personally you did not create even the smallest microscopic fragment of the materials out of which your opinion is made, and personally you cannot claim even the slender merit of putting the borrowed materials together. That was done—automatically—by your mental machinery, in strict accordance with the law of that machinery’s construction. And you not only did not make that machinery yourself, but you have not even any command over it.

Reading, by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, c. 1890–1895. Louvre Museum, Paris, France

Young Man

This is too much. You think I could have formed no opinion but that one?

Old Man

Spontaneously? No. And you did not form that one; your machinery did it for you—automatically and instantly, without reflection or the need of it.

Young Man

It’s an exasperating subject. The first man had original thoughts, anyway; there was nobody to draw from.

Old Man

It is a mistake. Adam’s thoughts came to him from the outside. You have a fear of death. You did not invent that—you got it from outside, from talk and teaching. Adam had no fear of death—none in the world.

Young Man

Yes he had.

Old Man

When he was created?

Young Man

No.

Old Man

When, then?

Young Man

When he was threatened with it.

Old Man

Then it came from the outside. Adam is quite big enough; let us not try to make a god of him. None but gods have ever had a thought which did not come from the outside. Adam probably had a good head, but it was of no sort of use to him until it was filled up from the outside. He was not able to invent the triflingest little thing with it. He had not a shadow of a notion of the difference between good and evil—he had to get the idea from the outside. Neither he nor Eve was able to originate the idea that it was immodest to go naked: the knowledge came in with the apple from the outside. A man’s brain is so constructed that it can originate nothing whatever. It can only use material obtained outside. It is merely a machine, and it works automatically, not by willpower. It has no command over itself, its owner has no command over it.

Young Man

Well, never mind Adam, but certainly Shakespeare’s creations—

Old Man

No, you mean Shakespeare’s imitations. Shakespeare created nothing. He correctly observed and he marvelously painted. He exactly portrayed people whom God had created but he created none himself. Let us spare him the slander of charging him with trying. Shakespeare could not create. He was a machine and machines do not create.

Young Man

Where was his excellence, then?

Old Man

In this: he was not a sewing machine like you and me; he was a Gobelin loom. The threads and the colors came into him from the outside; outside influences, suggestions, experiences (reading, seeing plays, playing plays, borrowing ideas, and so on) framed the patterns in his mind and started up its complex and admirable machinery, and it automatically churned out that pictured and gorgeous fabric which still compels the astonishment of the world. If Shakespeare had been born and bred on a barren and unvisited rock in the ocean his mighty intellect would have had no outside material to work with, and could have invented none; and no outside influences, teachings, moldings, persuasions, inspirations, of a valuable sort, and could have invented none; and so, Shakespeare would have produced nothing. In Turkey he would have produced something—something up to the highest limit of Turkish influences, associations and training. In France he would have produced something better—something up to the highest limit of the French influences and training. In England he rose to the highest limit attainable through the outside helps afforded by that land’s ideals, influences, and training. You and I are but sewing machines. We must turn out what we can; we must do our endeavor, and care nothing at all when the unthinking reproach us for not turning out Gobelins.

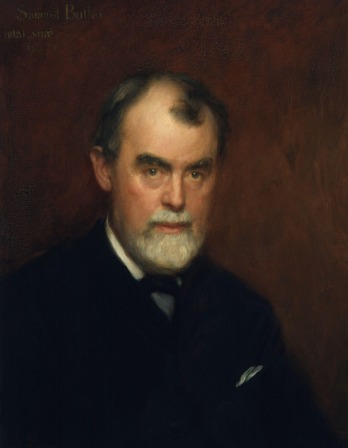

From “What is Man?” After his older brother bought the Hannibal Journal in 1851, Samuel Clemens set type and wrote sketches for the paper. He left home in 1853 at the age of seventeen, piloting steamboats on the Mississippi River and panning for gold in Nevada, before writing again for a newspaper in 1863 under the name “Mark Twain.” In 1935 Ernest Hemingway conceded, “All modern American literature comes from one book by Mark Twain called Huckleberry Finn.”

Back to Issue