Take back your golden fiddles, and we’ll beat to open sea.

—Rudyard Kipling, 1892The Curious Sensation of Drowning

The mechanics of watery death.

The SS Bokhara, ill-fated old tub, sailed from Shanghai, on the usual run to Colombo, with the homeward-bound mails on October 8, 1892, carrying between 130 and 150, crew and passengers. On the night of October 9, the vessel ran into a typhoon, from whose clutches she never escaped. Early in the morning of October 10, all the boats were lost, and the vessel lay in the trough of the sea, absolutely helpless, all efforts to get her to face the sea or run with it proving abortive.

All the afternoon the continuous hammering of the big seas on the doomed vessel went on, while night came only to add darkness to our other horrors—the faint glimmer of a tallow dip being a poor substitute for the electric light. Shortly after ten o’clock, three tremendous seas found their way down to the stokehole, putting out the fires, which had been banked all day, and our position was desperate. The end came shortly before midnight, when there was a heavy crash on a reef, and the Bokhara was at the bottom of the Strait of Formosa in less than a minute.

Lying jammed up in a corner of an already wrecked cabin, trying to get a few moments’ sleep, the terrific crash at once woke one up to the extreme gravity of the situation, and with scarcely time to think I pulled down the lifebelts and, throwing two to my companions, tied the third on myself and bolted for the saloon companionway, intending to reach the bridge or rigging. There was no time to spare for studying humanity at this juncture, but I can never forget the apparent want of initiative in all I passed. All the passengers seemed paralyzed—even my own companions, some of them able military men, had no idea of doing anything. The stewards of the ship, uttering cries of despair and last farewells, blocked up the saloon entrance to the deck, and it was only by sheer force I was able to squeeze past them—and just in time too, as the first heavy sea at once poured down the companionway. I saved myself from being washed down with it by standing in a corner of the deckhouse, the down-rushing water reaching to the middle of the body. My costume consisted at this time of a suit of pajamas, a singlet, and the lifebelt.

Getting out on deck, I at once made for the bridge and was climbing up the steps when a perfect mountain of water seemed to come from overhead, as well as from below, and dashed me against the bridge companion, steps and legs seeming to be inextricably mixed up. The same sea washed my head up against the bridge, causing, as I afterward found, a deep incised scalp wound, about four or five inches long, and knocking me insensible. The next thing I remember was trying to struggle through the rails of the upper bridge, which was now at the level of the water. The ship was evidently going down rapidly, and I was pulled down with her, still struggling to extricate myself. I got clear underwater, and immediately struck out to reach the surface as I thought, but evidently only to go farther down. This exertion was a serious waste of breath, and after what appeared to be ten or fifteen seconds, the effort of inspiration could no longer be restrained, and pressure on the chest began to develop. Probably the most striking thing to remember at this period of time was the great pain produced in the chest, and which increased at every effort of expiration and inspiration; it seemed as if one were in a vice, which was gradually being screwed up tight until it felt as if the sternum and spinal column must break. Many years ago, my old teacher, Henry Littlejohn, used to describe how painless and easy a death by drowning was—“like falling about in beautiful green fields in early summer”—this flashed across my brain at the time, and I said to myself, “Poor old devil, Littlejohn—scarcely so accurate that time.” The “gulping” process became more frequent for about ten efforts, and hope was then extinguished. Even though I had seen no land, I felt sure there must be some near and had hoped to get to the surface again to make an effort to reach it. The pressure after these ten rapid gulps seemed unbearable, but gradually the pain seemed to ease up as the carbonic acid was accumulating in the blood. At the same time the efforts at inspiration with their accompanying gulps of water occurred at longer and longer intervals. My mental condition was now such that I appeared to be in a pleasant dream, although I had enough willpower to think of friends at home and still retain vivid recollections of sights from my boyhood. Before finally losing consciousness, the chest pain had completely disappeared, and sensation was actually pleasant. What time I had then passed in the water I cannot possibly say—but I should think about two minutes; I was greatly handicapped below water by the previous exertion in getting on deck, and then by the stunning blow on the head, with the result that instead of going down after a full inspiration, there was actually very little more than residual air in the lungs. Then the useless attempt to reach the surface would further reduce the time necessary to produce unconsciousness. What happened when inspiration was attempted was that the mouth was immediately filled with water, and the epiglottis closing or closed down on the larynx, the act of swallowing at once occurred. I think the only time the epiglottis was not closed down was during the short expirations which took place after every attempt at inspiration.

The article on drowning in the Encyclopedia Britannica says, “The drowned individual struggles to reach the surface of the water in his efforts to respire—as he does so he draws water into his windpipe which provokes cough.” I cannot see how it is possible for a man underwater to cough, and I do not believe that any water will get into the trachea until after unconsciousness comes on. I have made postmortem examination of scores of drowned bodies in Hong Kong, and “froth in the trachea” is anything but a constant sign. Where efforts at artificial respiration have been made, one would expect this frothy condition, or if in drowning they had come to the surface once or twice.

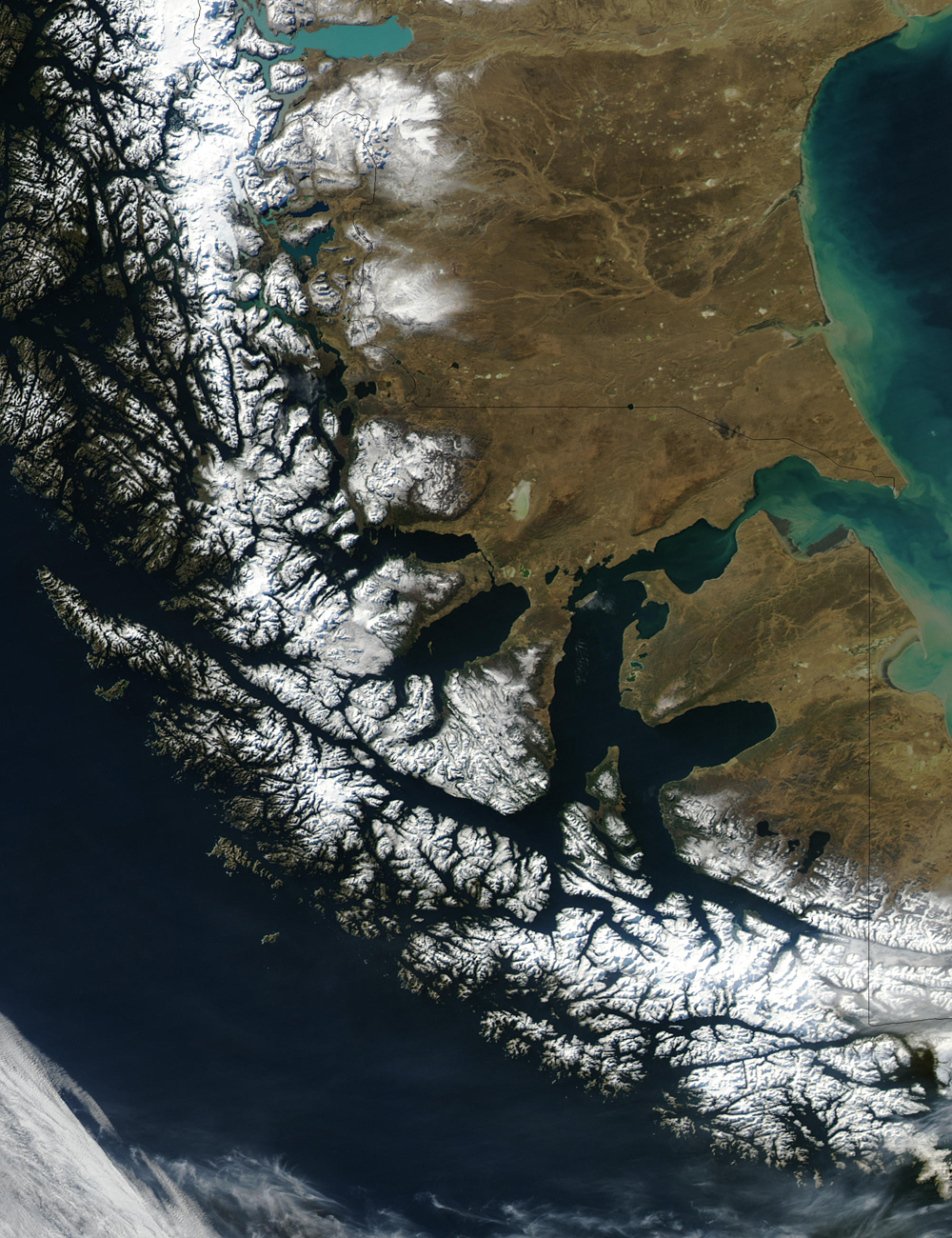

Strait of Magellan from space, 2003. © Jacques Descloitres, MODIS Rapid Response Team, NASA/GSFC.

To go on with the narrative: consciousness returned, and I found myself at the surface of the water, and managed to get about a dozen good inspirations. A hurried glance showed me the land apparently about four hundred yards distant, and I proceeded to utilize first a bale of silk and then a long wooden plank to assist me to the shore. These and the lifebelt were of the greatest use also in saving my body from being bashed about on the reef in the tempestuous sea. As it was, feet, knees, and the regions of the anterior superior iliac spine were considerably lacerated. On landing and getting behind a sheltering rock, no effort was required to produce copious emesis.

James Lowson

From “Sensations in Drowning.” A doctor formerly in the Hong Kong civil service, Lowson published this account in 1903 in The Edinburgh Medical Journal—it appeared after “Syphilis and Life Assurance” by Byrom Bramwell and before “Softening About the Right Calcarine Fissure, Associated with Left Hemianopia” by J. Arthur Perdrau—and concluded his article with the note, “The personal character of this narrative must be my apology for the frequent use of the first personal pronoun.”