Some are born to sweet delight,

Some are born to endless night.

The Hero of a Thousand Dreams

A reconsideration of Winsor McCay’s Little Nemo in Slumberland.

By John Crowley

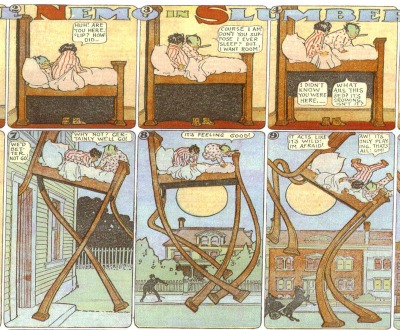

Little Nemo in Slumberland, by Winsor McCay, July 26, 1908. The Comic Strip Library.

But the quincunx of heaven runs low, and ’tis time to close the five ports of knowledge.

—Thomas Browne, The Garden of Cyrus

Nights are dark, but dreams are alight. On an October Sunday in 1905, a new story appeared in the comics section of the New York Herald, alongside Richard F. Outcault’s beloved Buster Brown and his dog Tige, and Winsor McCay’s six-panel Little Sammy Sneeze. The full-page strip was a revelation: a McCay adventure titled Little Nemo in Slumberland. The title bar across the top of the page showed a gigantic bearded figure in a vast architectural space, leaning a muscled arm on the border of the panel; he is Morpheus, king of Slumberland. He speaks to a little Maxfield Parrish–like figure, who stands on the same border, bowing deeply in assent as he is given instructions: “His Majesty requests the presence of little Nemo.” In the next panel this figure appears in a little boy’s bedroom. A caption under the picture identifies him as an Oomp, here to bring Nemo to the king. “And I’ve brought a little spotted night horse for you to ride,” he says. “His name is Somnus, and he’s as gentle as can be.” Nemo, “surprised as well as delighted to receive the king’s invitation,” sets off and pretty quickly falls in with a number of queer animals riding on other animals through the night sky. More animals show up, the child is challenged to a race, exploding stars or fireworks go off around them, Nemo can’t control his steed and is flung off into featureless darkness, falling and calling for Mama and Papa. “Becoming so dizzy that he thought he was going to die, he began to scream,” says the caption, “when he awoke.” And there he is in the last panel, back in his bedroom, having fallen out of bed.

Readers were captivated, by the strangeness and the imagery, and by the brilliant color printing that the Herald pioneered. The bold inventiveness—which would grow bolder, stranger, more gorgeous, more teasing over many subsequent Sundays—brought to readers not only laughter and delight but a species of awe that’s still possible to experience in the Sunday pages, reissued most recently in 2014 by Taschen.

Unlike his near-contemporary dream tellers Freud and Kafka, McCay was cheerfully repressed, gregarious, not a deep thinker, but it seems certain that he was a great and perhaps troubled dreamer. John Canemaker, in his exhaustive 1987 biography, records no dreams of McCay’s except the ones he created on paper, but in a sense McCay was his drawings, and his dreams are the ones he drew. Born in Canada in 1867, he began drawing as a child and hardly ceased drawing all his working life. He had a natural gift for capturing perspective, detail, and bodily expression (though faces interested him less). He took work in Columbus and Cincinnati, where he drew all the things that needed to be shown in his adopted America: circus posters, city views, vaudeville ads, and comic strips and pictures. At his most productive, he drew in ink on white card, with only a square and a triangle, using a board set in his lap and propped on the edge of a desk. His vast repertoire of architectural detail was in his head and his fingers; he never kept a sketchbook or copied photographs. The architectural vistas, often filled with great crowds of beings in motion, that made up Slumberland were newly created every week.

American soldier seen through night-vision goggles, Khost Province, Afghanistan, 2005. Photograph by Moises Saman. © Moises Saman / Magnum Photos.

It’s inconceivable that a little boy of five could dream Nemo’s dreams: the wondrous Beaux-Arts or City Beautiful architecture, the huge cast of unreal characters, the elaborate jokes. But it is true that McCay and his family (including his little curly-haired son, Robert, the model for Nemo) lived in Sheepshead Bay in Brooklyn, not far from the great Coney Island attractions of Luna Park and Dreamland. Luna Park, the more bon ton of the two, opened in 1903, its remarkable towers and promenades “oriental” in conception but fanciful in fact and lit magically with 250,000 light bulbs (Dreamland, which opened a year later, claimed to have even more). Slumberland, of course, needed none, but fantasy architecture arising around twisting intersections of boulevards, escalators, archways, fountains, balloon ascensions, and crowds certainly came to be incorporated in McCay’s relatively huger and more labile spaces. Robert, born in 1896, was no doubt taken to both parks, and it’s possible they filled his dreams with wondrous palaces, eruptions of surreal distortion, malevolent inanimate objects, falls from great heights, reversals of expectation, and getting badly lost. Nemo’s evolving adventures can be considered the great American dream journey, as Alice’s adventures underground and through the mirror are for the English. But where the challenges Alice faces and the puzzles she must solve are verbal, Nemo’s are visual: like Alice he grows and shrinks, but he also becomes monstrously fat; grows up, grows old, approaches death; is dressed as a girl, a pirate, a soldier, a courtier; becomes flat as a postcard; and only once (July 4, 1909) is driven to ask, “I wonder what this all means anyhow?”

In his keynote address to the 2017 conference of the International Association for the Study of Dreams, the psychologist G. William Domhoff claimed that most of our dreams take place in what are effectually the spaces of our daytime lives and are largely taken up with the things we commonly do there. Perhaps it’s so for a majority of us most of the time; but I believe any dreamer can be touched by the power to create wonder and terror, persons and places never seen before and existent nowhere else. Like libraries of books, the libraries of collected dreams—there are several, and some are vast—contain mostly the arid and the dull, but the small number of genius dreamers who occur in every part of society, every class and nation, have the power not only to dream vastly but also to relate those dreams in the light of day. Retold dreams have necessarily to take a more solid and unchanging form than the endlessly mutating conditions of real dreams, large parts of which remain meaningless and are soon forgotten or never remembered at all, edited out by the dreamer and then by the storyteller; but potent dreams, news brought out of nowhere, can puzzle or shock spouses when told, awe neighbors, unsettle rulers, even set in motion events that upend the order of a society or a faith.

The dreams reported by dreamers in older cultures were commonly interpreted as allegories, quickly resolved into sense by expert decoders: they bring instructions from divine beings, guides for action, promises of good fortune, or warnings of danger. In the first book of his Histories, the Greek historian Herodotus relates a dream of Astyages, king of the Medes, in which the king perceived his daughter Mandane urinating so ceaselessly that she flooded the royal city and then drowned all Asia. Later he dreamed that she gave birth to a vine that grew to overspread the continent. The Median priests gave assuring or unsettling interpretations, but the dreams themselves, passed down through the ages, have escaped divination; and though the furnishings and behaviors in them, like the meanings derived from them, are not ours, they can sometimes strike us as like our own: my younger sister once dreamed of vomiting continuously, which she found not particularly distressing in the dream, except for the endless mopping it entailed.

Peoples around the world and through time have separately developed theories of dreaming that posit a multipart soul: the “body soul” is the part that keeps the person alive and animate, that perishes with the body or survives it, is reborn or not. The “free” or “separable soul” can leave the living body in dreams or trance, travel to different realms within death’s domain, defeat monstrous enemies or be defeated by them, visit with dead heroes and relatives, learn secrets, and return again to the body. The adventures and misadventures of the “free soul,” when retold to the community, can structure concepts of afterlives where punishment or reward is allotted for what was done in physical life. So general are these beliefs throughout human societies, from Australian dream tales to Inuit shamanic journeys to European witches’ Sabbaths, that they can seem foundational, maybe dating to the practices of our oldest ancestor bands, carried around the world as they spread. Or—possibly—it’s simply so.

Unlike those told by our earliest ancestors, many of the dream-journey stories created by cultural technicians in societies that deploy writing and books, and later, films, originate not in true dreaming but as moral tracts or treatises in psychology or theology. John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress is said by the author to be “delivered under the similitude of a dream,” and begins as one:

As I walked through the wilderness of this world, I lighted on a certain place where was a den: and I laid me down in that place to sleep: and as I slept I dreamed a dream. I dreamed, and behold, I saw a man clothed with rags, standing in a certain place, with his face from his own house, a book in his hand, and a great burden upon his back.

Thereafter the story is simply a story about this man, Christian, told in the third person, and the dream convention is discarded. Alice’s stories are told in the same way, her journeys (like Christian’s) taking her from challenge to challenge, as described in the third person by her author, until she refuses to play along anymore (“You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”) and wakes, to learn she was only dreaming. Perhaps Alice can be seen as the wandering free soul of her creator, and his tale the chastened or legible version of a far stranger journey.

The dreams I have, and dreams I have heard retold, seem to have no prologues, no beginnings. We don’t set out, like Christian or Alice; we simply find ourselves in the places where we are. “Indistinct beginning,” Sigmund Freud reports of one of his own dreams:

I tell my wife I have some news for her, something very special. She becomes frightened, and does not wish to hear it. I assure her that, on the contrary, it is something which will please her greatly, and I begin to tell her that our son’s officers’ corps has sent a sum of money…something about honorable mention…distribution…at the same time I have gone with her into a small room, like a storeroom, in order to fetch something from it. Suddenly I see my son appear; he is not in uniform but rather in a tight-fitting sports suit (like a seal?) with a small cap. He climbs onto a basket that stands to one side near a chest, in order to put something on this chest. I address him; no answer. It seems to me that his face or forehead is bandaged, he arranges something in his mouth, pushing something into it. Also, his hair shows a glint of gray. I reflect: Can he be so exhausted? And has he false teeth?

The style of dream telling that Sigmund Freud instituted closely relates to the narrative style of certain modern writers, and may well have influenced some: the beginning in the middle of things, in the present tense; the uncertainty of the dreamer as to how he came to be where he is or doing what he is doing; the strange indifference in the face of unsettling or horrid changes to people and things; the ending in ambiguity. However Freud interpreted it, his dream about his son seems entirely authentic as dream, but is that because it now sounds to us like a story of Kafka’s?

Night View of the Grand Canal, Venice, by Carlo Naya, c. 1875. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of Estate of Emily Delafield Floyd, 1961 (CC0).

My own dreams trend to the Kafkaesque; like Nemo’s they are often set in shape-shifting or fearsome architectural spaces where I must (and can’t) find my way, but where mine are commonly shabby, unintelligible, cluttered, and dark, his remain gorgeous and bright. Nemo (whose name is “nobody,” of course, as wandering Ulysses once called himself) is a romance hero, beset by enemies, often afraid, aided by guides, seeking his anima, and tricked by false or artificial versions who must be seen through before the final consummation (“Woman, in the picture language of mythology, represents the totality of what can be known. The hero is the one who comes to know,” in Joseph Campbell’s formulation, though Nemo finally comes to know very little). I am rarely given such tasks to do, and if I am, I stumble or wander away along other streets and into other spaces before failing or forgetting them and often wake conscious of my failure.

The readers of the original colored pages experienced the dreams of Nemo differently from the dreams we have or hear about from others. For one thing, the whole story of Nemo’s journeys to Slumberland is continuous, one colored dream per Sunday, every night a further chapter—I know of no one who dreams in such a way. Also, the journey begins not with Nemo but with that immense king of Slumberland, who orders his servants to find a way to bring Nemo to his palace so he can be a friend to his Nemo-sized daughter; successive pages show more servants making further plans as each fails to bring Nemo to Slumberland. (I think there are few dreams that incorporate scenes in which the dreamer doesn’t figure even as observer: third-person point of view dreams, so to speak.) Also, for many months each dream—there are a few exceptions—is plotted in the same way: the night journey begins, seems promising, and is frustrated; Nemo meets obstacles, or trips himself up, or breaks some dreamland prohibition; the various creatures sent to guide him desert or hinder him. The last panel always shows him having fallen out of bed, or standing on the bed in the way children do, crying out, not awake and yet no longer asleep. He has to be scolded or comforted by Mother, or Father, or Grandma—who all note that he should never have eaten that cheese pie or other snack before bedtime.

(Is it really the case that eating certain foods—especially, for some reason, foods containing or consisting of cheese—cause weird or disturbing dreams? Of course the idea is embedded deep in popular lore; one of the strips that made McCay’s name in New York was called Dream of the Rarebit Fiend, detailing strange dreams resulting from nighttime consumption of the eponymous dish. Nemo’s parents blame his dreams on cheese pie, turkey dressing, sardines, peanuts, raisin cake, and doughnuts; eventually such explanations are given up.)

She Never Told Her Love (detail), by Henry Peach Robinson, 1857. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Purchase, Jennifer and Joseph Duke Gift, 2005 (CC0).

McCay kept the Nemo strip going long after the rather subdued meeting of Nemo and his princess, with visual transformations and effects unequaled in comic art but also a large amount of lifeless prettiness resembling the pageant, that peculiar entertainment of the period. Eventually, though he never stops waking up in alarm or puzzlement, Nemo never quite seems to be home, as though he has become a citizen of Slumberland for good.

The last of the original run of Nemo Sunday strips was published on July 23, 1911. (There was a further iteration that ran in the Herald with increasing weariness until 1926.) By then a huge Broadway spectacle based on the strip, with music by Victor Herbert (Babes in Toyland), had absorbed McCay’s attention. He’d also become a vaudeville star, at first doing lightning sketches to tell a story along with a verbal patter, and then showing his brief animated films—he is classified among the pioneers of animation. “The future successful artist will be one whose pictures move,” McCay wrote in 1912. “Nor is this a radical statement, quite the reverse, for just see the furor my Little Nemo drawings, the first of these paintings shown via the moving picture route, made in artistic circles both here and abroad. ” By the time he died, in 1934, the power of popular media to replicate the processes of dream time had broadly expanded, from comic strips and the comic book into the animated cartoons of Max Fleischer and Walt Disney, and thence to live-action movies with their rapid cutting, close-ups, movement, voices. In her discussion of virtuality in art, the philosopher Susanne K. Langer defined film as virtual dreaming, experienced as “a unified, continuously passing, significant apparition”—a triumph of the cultural technology that McCay played his part in creating.

No one at the breakfast table or the watercooler can challenge the dreams we claim to have had, but we need not be believed either—all the witnesses have vanished with the day. We certainly are conscious in those dreams, but like Nemo we aren’t conscious of what we have dreamed until we wake. The philosopher and student of consciousness John Searle writes that

it does not seem to me that consciousness is hard to define. Consciousness consists of states of awareness or sentience or feeling. These typically begin in the morning when you wake up from a dreamless sleep and go on all day until you go to sleep or otherwise become “unconscious.” According to this definition, dreams are a form of consciousness.

But can we say we’ve been conscious in dreams if we remember nothing of them? All that creativity can’t be said to be wasted—there’s the common (but I think so far not exactly proven) theory that dreams are in effect the shredding of unwanted or useless amalgamations of daylight experience and thought. That’s what the strange writer Thomas Browne, Bunyan’s contemporary, believed: “We are unwilling to spin out our awaking thoughts into the phantasms of sleep, which often continueth precogitations; making cables of cobwebs and wildernesses of handsome groves.” Better Searle’s “dreamless sleep,” if any is so, than anxious dreams and haunted wildernesses.

Browne knew that when it’s time to close the five ports of knowledge (the senses), not all would open again in dreams; what is seen can’t be touched, what we think we smell has no odor, so that

there is little encouragement to dream of paradise itself. Nor will the sweetest delight of gardens afford much comfort in sleep; wherein the dullness of that sense shakes hands with delectable odors, and though in the bed of Cleopatra can hardly with any delight raise up the ghost of a rose.

But Browne knew something more: “I am in no way facetious,” he writes, “nor disposed for the mirth and galliardise of company; yet in one dream I can compose a whole comedy, behold the action, apprehend the jests, and laugh myself awake at the conceits thereof.” Browne only knew what he laughed at when the laugh awoke him, just as Nemo only knows where he has been when he wakes up in his bedroom.

Living is an ailment that is relieved every sixteen hours by sleep. A palliative. Death is the cure.

—Sébastien-Roch Nicolas Chamfort, 1790This is what we know of dreamland: we know ourselves to be there when we are there, but we don’t know we know. Only when we awaken are we conscious of what we did and felt, and then only of those parts of the night’s dreaming that we remember. Like Nemo we wake ourselves with laughter or cries of terror, and only then know why. The rest is lost, and effectually we never experienced it.

Perhaps this could be said of the sleep of death as well. We humans have long lived in two worlds: the one of life and a prospective one after that life. We have always had a path to the next world while alive, in dreams. In fact it seems reasonable to think that the knowledge of an afterlife might have begun in the remembering and sharing of dreams, and not solely in the general human conviction that we can’t possibly be extinguished entirely. And indeed it’s possible to think that if there were to be consciousness beyond death, and a land or realm where it continues, that realm would be as shifting and full of wonders and terrors and puzzlements as are our most memorable dreams: a life in which we think we are wounded but can’t feel pain, are given food but can’t taste it, and can hardly summon up the ghost of a rose; where friends and relatives long dead appear alive; where we never wake up laughing at what we have conceived, and never fall out of bed like Nemo into wakefulness and memory, but simply continue to walk and wonder, citizens of Slumberland forever.