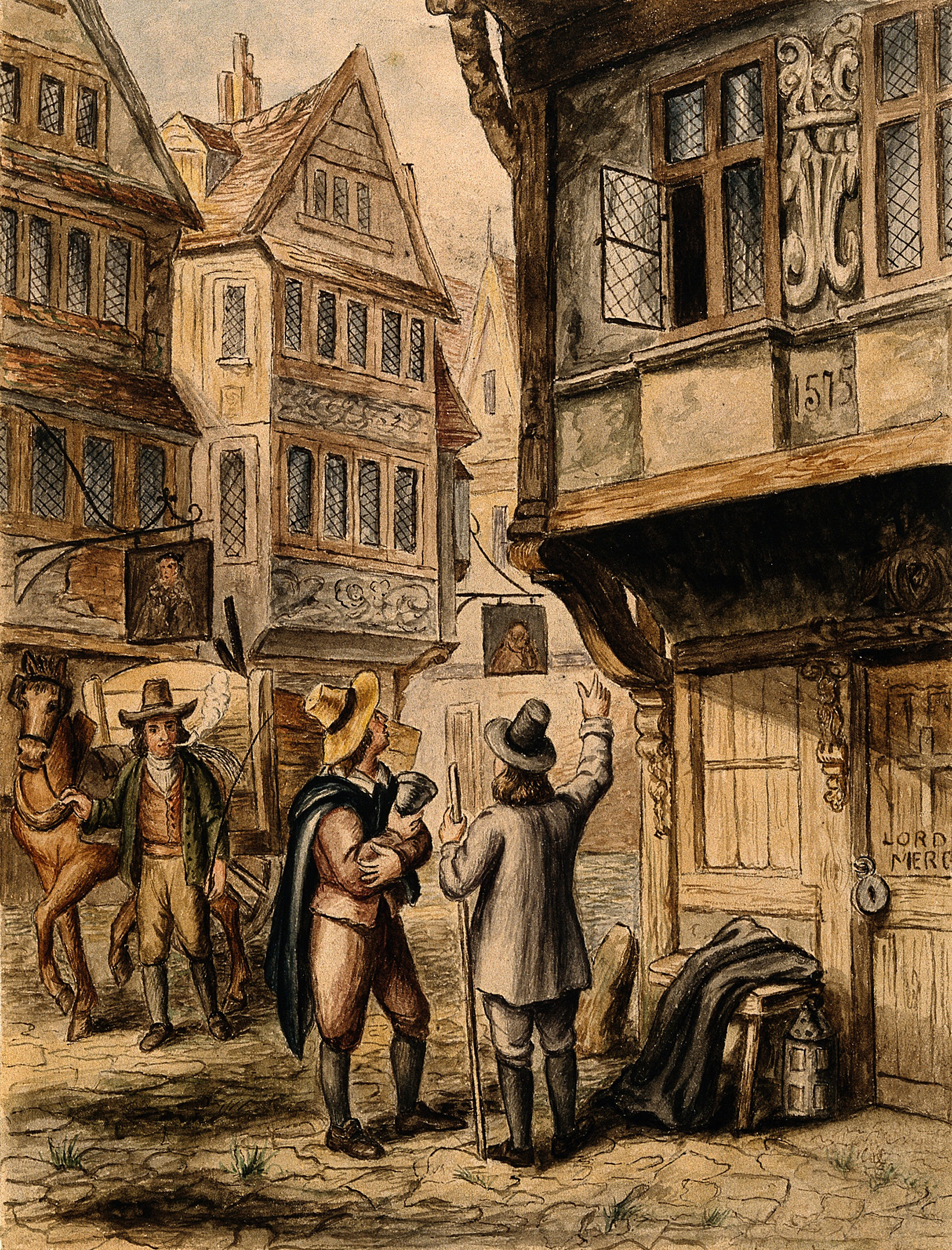

A cart for transporting the dead in London during the Great Plague, by or after George Cruikshank, nineteenth century. Wellcome Collection (CC BY 4.0).

In the weeks ahead, as the world continues to reckon with and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories dealing with quarantine, unfathomable deaths, isolation, dread, and attempts to find community when the rest of the world feels far away.

It’s likely that nearly a hundred thousand people—a quarter of London—died during the Great Plague of 1665. Transmitted by flea-covered rats, the bubonic plague started with a fever, and its victims then erupted in boils on their groins, their armpits, seemingly anywhere uncomfortable for an abscess to appear. People usually died within a week of contracting the bacterial infection, vomiting up bile and blood until they expired. Thirty-two-year-old Samuel Pepys watched the plague ravage London, dutifully recording how the city emptied as he continued to work, socialize, and dream of assignations.

June 7, 1665

This day, much against my will, I did in Drury Lane see two or three houses marked with a red cross upon the doors, and “Lord have mercy upon us” writ there; which was a sad sight to me, being the first of the kind that, to my remembrance, I ever saw. It put me into an ill conception of myself and my smell, so that I was forced to buy some roll tobacco to smell and to chaw, which took away the apprehension.

June 10

Lay long in bed, and then up and at the office all the morning. At noon dined at home, and then to the office busy all the afternoon. In the evening home to supper; and there, to my great trouble, hear that the plague is come into the City (though it hath these three or four weeks since its beginning been wholly out of the City); but where should it begin but in my good friend and neighbor Dr. Burnett, in Fanchurch Street: which in both points troubles me mightily. To the office to finish my letters and then home to bed, being troubled at the sickness, and my head filled also with other business enough, and particularly how to put my things and estate in order, in case it should please God to call me away, which God dispose of to his glory!

July 20

So walked to Redriffe, where I hear the sickness is, and indeed is scattered almost everywhere, there dying 1,089 of the plague this week. My Lady Carteret did this day give me a bottle of plague water home with me. So home to write letters late, and then home to bed, where I have not lain these three or four nights. I received yesterday a letter from my Lord Sandwich, giving me thanks for my care about their marriage business, and desiring it to be dispatched that no disappointment may happen therein, which I will help on all I can. This afternoon I waited on the Duke of Albemarle, and so to Mrs. Croft’s, where I found and saluted Mrs. Burrows, who is a very pretty woman for a mother of so many children. But Lord! to see how the plague spreads. It being now all over King’s Street, at the Axe, and next door to it, and in other places.

August 15

Up by four o’clock and walked to Greenwich, where called at Captain Cocke’s and to his chamber, he being in bed, where something put my last night’s dream into my head, which I think is the best that ever was dreamt, which was that I had my Lady Castlemayne in my arms and was admitted to use all the dalliance I desired with her, and then dreamt that this could not be awake, but that it was only a dream; but that since it was a dream, and that I took so much real pleasure in it, what a happy thing it would be if when we are in our graves (as Shakespeare resembles it) we could dream, and dream but such dreams as this, that then we should not need to be so fearful of death, as we are this plague time.

Here I hear that news is brought Sir G. Carteret that my Lord Hinchingbrooke is not well, and so cannot meet us at Cranborne tonight. So I to Sir G. Carteret’s; and there was sorry with him for our disappointment. So we have put off our meeting there till Saturday next.

It was dark before I could get home, and so land at churchyard stairs, where, to my great trouble, I met a dead corpse of the plague, in the narrow alley just bringing down a little pair of stairs. But I thank God I was not much disturbed at it. However, I shall beware of being late abroad again.

August 31

Up and, after putting several things in order to my removal, to Woolwich; the plague having a great increase this week, beyond all expectation of almost 2,000.

Thus this month ends with great sadness upon the public, through the greatness of the plague everywhere through the kingdom almost. Everyday sadder and sadder news of its increase. In the City died this week 7,496, and of them 6,102 of the plague. But it is feared that the true number of the dead this week is near 10,000; partly from the poor that cannot be taken notice of, through the greatness of the number, and partly from the Quakers and others that will not have any bell ring for them.

As to myself I am very well, only in fear of the plague, and as much of an ague by being forced to go early and late to Woolwich, and my family to lie there continually.

September 3

(Lord’s day.) Up; and put on my colored silk suit very fine, and my new periwig, bought a good while since but durst not wear, because the plague was in Westminster when I bought it; and it is a wonder what will be the fashion after the plague is done as to periwigs, for nobody will dare to buy any hair, for fear of the infection, that it had been cut off of the heads of people dead of the plague.

Church being done, my Lord Bruncker, Sir J. Minnes, and I up to the vestry at the desire of the justices of the peace, Sir Theo. Biddulph and Sir W. Boreman and Alderman Hooker, in order to the doing something for the keeping of the plague from growing; but Lord! to consider the madness of the people of the town, who will (because they are forbid) come in crowds along with the dead corpse to see them buried; but we agreed on some orders for the prevention thereof. Among other stories, one was very passionate, methought, of a complaint brought against a man in the town for taking a child from London from an infected house.

Alderman Hooker told us it was the child of a very able citizen in Gracious Street, a saddler, who had buried all the rest of his children of the plague, and himself and wife now being shut up and in despair of escaping, did desire only to save the life of this little child; and so prevailed to have it received stark naked into the arms of a friend, who brought it (having put it into new fresh clothes) to Greenwich; whereupon hearing the story, we did agree it should be permitted to be received and kept in the town. Thence with my Lord Bruncker to Captain Cocke’s, where we mighty merry and supped, and very late I by water to Woolwich, in great apprehensions of an ague. Here was my Lord Bruncker’s lady of pleasure, who, I perceive, goes everywhere with him; and he, I find, is obliged to carry her, and make all the courtship to her that can be.

September 7

Up by five of the clock, mighty full of fear of an ague, but was obliged to go, and so by water, wrapping myself up warm, to the Tower, and there sent for the Weekly Bill, and find 8,252 dead in all, and of them 6,878 of the plague; which is a most dreadful number, and shows reason to fear that the plague hath got that hold that it will yet continue among us.

September 14

When I came home I spent some thoughts upon the occurrences of this day, giving matter for as much content on one hand and melancholy on another, as any day in all my life. For the first, the finding of my money and plate, and all safe at London, and speeding in my business of money this day. The hearing of this good news to such excess, after so great a despair of my lord’s doing anything this year; adding to that, the decrease of five hundred and more, which is the first decrease we have yet had in the sickness since it begun: and great hopes that the next week it will be greater.

Then, on the other side, my meeting dead corpses of the plague, carried to be buried close to me at noon through the city in Fanchurch Street. To see a person sick of the sores, carried close by me by Gracechurch in a hackney coach. My finding the Angell Tavern, at the lower end of Tower Hill, shut up, and more than that, the alehouse at the Tower stairs, and more than that, the person was then dying of the plague when I was last there, a little while ago, at night, to write a short letter there, and I overheard the mistress of the house sadly saying to her husband somebody was very ill but did not think it was of the plague. To hear that poor Payne, my waiter, hath buried a child and is dying himself. To hear that a laborer I sent but the other day to Dagenhams, to know how they did there, is dead of the plague; and that one of my own watermen, that carried me daily, fell sick as soon as he had landed me on Friday morning last, when I had been all night upon the water (and I believe he did get his infection that day at Brainford), and is now dead of the plague. To hear that Captain Lambert and Cuttle are killed in the taking these ships; and that Mr. Sidney Montague is sick of a desperate fever at my Lady Carteret’s, at Scott’s Hall. To hear that Mr. Lewes hath another daughter sick. And, lastly, that both my servants, W. Hewer and Tom Edwards, have lost their fathers, both in St. Sepulchre’s parish, of the plague this week do put me into great apprehensions of melancholy, and with good reason. But I put off the thoughts of sadness as much as I can, and the rather to keep my wife in good heart and family also.

December 31

It is true we have gone through great melancholy because of the great plague, but now the plague is abated almost to nothing, and I intending to get to London as fast as I can. I have never lived so merrily (besides that I never got so much) as I have done this plague time, by my Lord Bruncker’s and Captain Cocke’s good company, and the acquaintance of Mrs. Knipp, Coleman and her husband, and Mr. Laneare, and great store of dancings we have had at my cost (which I was willing to indulge myself and wife) at my lodgings. The great evil of this year, and the only one indeed, is the fall of my Lord of Sandwich.

My whole family hath been well all this while, and all my friends I know of, saving my Aunt Bell, who is dead, and some children of my cousin Sarah’s, of the plague. But many of such as I know very well, dead; yet, to our great joy, the town fills apace, and shops begin to be open again. Pray God continue the plague’s decrease! For that keeps the court away from the place of business, and so all goes to rack as to public matters, they at this distance not thinking of it.

Read the other entries in our series: Heinrich Heine, George Eliot, Willa Cather, Lucretius, Thomas Mann, Jack London, John Keats, Alessandro Manzoni, Giovanni Boccaccio, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Daniel Defoe, François Rabelais, and Robert Louis Stevenson.