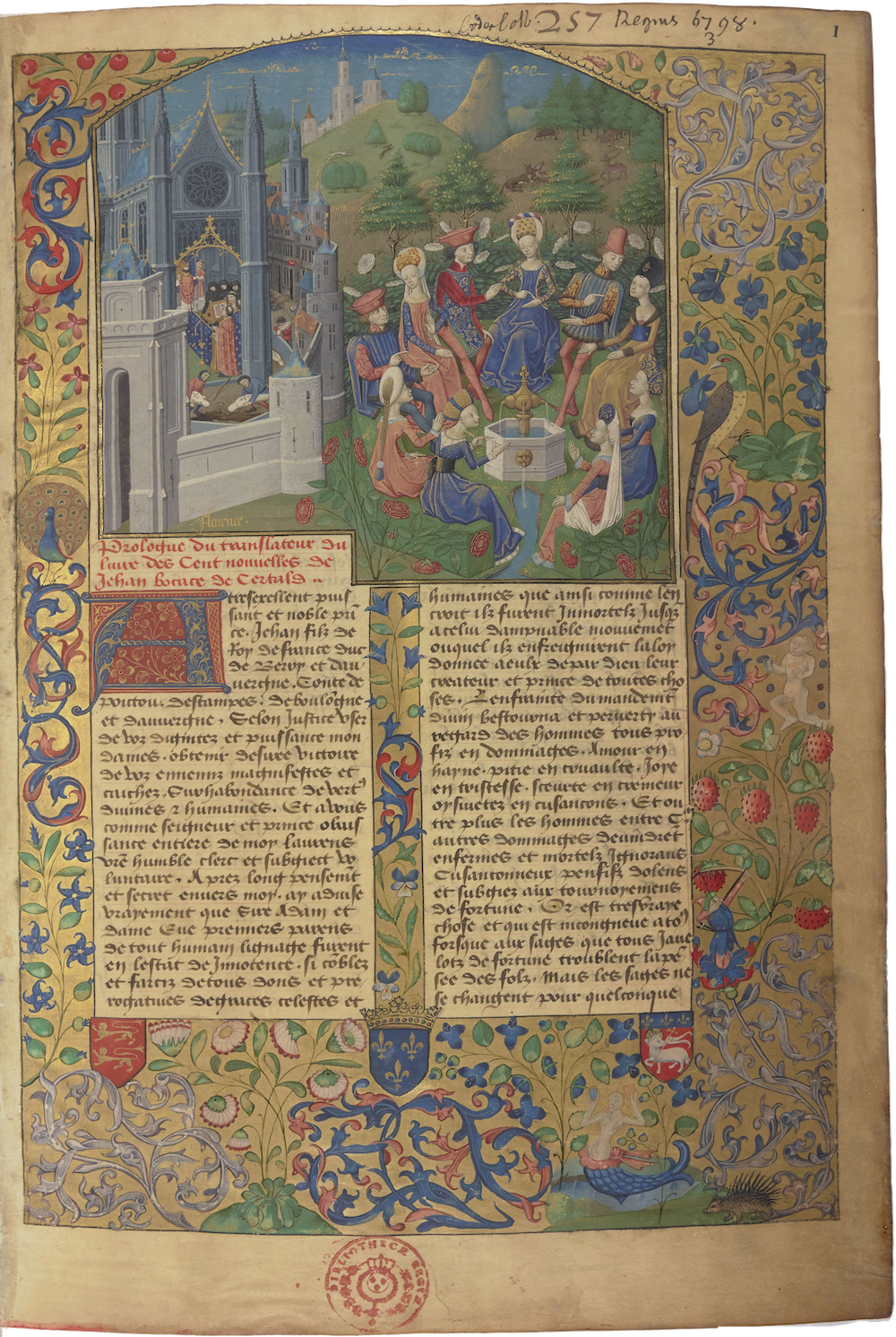

An illustration from a manuscript copy of The Decameron, c. 1414. Bibiliothèque nationale de France.

In the weeks ahead, as the world continues to reckon with and respond to the COVID-19 pandemic, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories dealing with quarantine, unfathomable deaths, isolation, dread, and attempts to find community when the rest of the world feels far away.

Giovanni Boccaccio’s The Decameron, completed in 1353 and known for containing one hundred stories within its pages, is set in Florence during the 1348 bubonic plague outbreak. Boccaccio describes the plague as particularly virulent, not just moving from person to person but also spread by the inanimate objects a plague victim had owned or touched. Many Florentines began shunning the ill, shutting themselves up in houses only with other healthy people and maintaining abstemious lifestyles. Others engaged in revelry, growing reckless in the face of death. Some adopted a middle path; still others fled the city. Each group saw some of its members sicken and die. The Decameron’s one hundred stories are recounted by ten young people who have decided to flee.

On a Tuesday after church service at Santa Maria Novella, seven young women discussed the plague that had befallen Florence. The eldest, Pampinea, suggested that remaining in the city would only afford them a front-row seat to death and disease, and that they could better ensure their own health and safety if they moved to a house in the countryside with their maids and their belongings. The excerpt below, adapted from the 1903 translation by J.M. Rigg, begins after the women all readily agree to this plan and discuss whether they should invite anyone else to join them.

While the seven ladies were conversing, three young men came into the church, young, but not so young that the age of the youngest was less than twenty-five years; neither the sinister course of events, nor the loss of friends or kinsfolk, nor fear for their own safety, had availed to quench, or even temper, the ardor of their love. The first was called Pamfilo, the second Filostrato, and the third Dioneo. Very debonair and chivalrous were they all; and in this troublesome time they were seeking if they might have sight of their fair friends, all three of whom chanced to be among the said seven ladies, besides some that were of kin to the young men. At one and the same moment they recognized the ladies and were recognized by them. With a gracious smile, Pampinea began speaking, “Lo, fortune is propitious to our enterprise, having vouchsafed us the good offices of these young men, who are as gallant as they are discreet, and will gladly give us their guidance and escort, so we but take them into our service.”

Neifile, crimson from brow to neck with the blush of modesty, being one of those that had a lover among the young men, said, “For God’s sake, Pampinea, have a care what you say. Well assured am I that naught but good can be said of any of them, and I deem them fit for office far more onerous than this which you propose for them, and their good and honorable company worthy of ladies fairer by far and more tenderly to be cherished than such as we. But ’tis no secret that they love some of us here; wherefore I misdoubt that, if we take them with us, we may thereby give occasion for scandal and censure merited neither by us nor by them.”

“That,” said Filomena, “is of no consequence; I live honestly, my conscience gives me no disquietude. If others asperse me, God and the truth will take arms in my defense. Now, should they be disposed to attend us, we might say with Pampinea that fortune favors our enterprise.”

The following silence signaled the other ladies’ consent; they resolved to call the young men, acquaint them with their purpose, and ask them to join their party. So without further parley Pampinea, who had a kinsman among the young men, rose and approached them where they stood intently regarding them. Greeting them gaily, she opened to them their plan, and besought them on the part of herself and her friends to join their company on terms of honorable and fraternal comradeship. At first the young men thought she trifled with them; when they saw that she was in earnest, they answered with alacrity that they were ready and promptly, even before they left the church, set matters in train for their departure.

The ladies with some of their maids and the three young men, each attended by a manservant, took the road on Wednesday at daybreak; they had not journeyed more than two miles when they arrived at their destination. The estate lay upon a little hill some distance from the nearest highway, and, embowered in shrubberies of diverse hues and other greenery, afforded the eye a pleasant prospect. On the summit of the hill was a palace with galleries, halls, and chambers disposed around a fair and spacious court, each very fair in itself and set amid meads and gardens laid out with marvelous art, wells of the coolest water, and vaults of the finest wines, things more suited to dainty drinkers than to sober and honorable women. On their arrival the company, to their no small delight, found their beds already made, the rooms well swept and garnished with flowers of every sort that the season could afford, and the floors carpeted with rushes.

When they were seated, Dioneo, a gallant who had not his match for courtesy and wit, spoke: “My ladies, ’tis not our forethought so much as your own mother wit that has guided us hither. How you mean to dispose of your cares I know not; mine I left behind me within the city gate when I issued thence with you a brief while ago. Wherefore, I pray you, either address yourselves to make merry, to laugh and sing with me (so far, I mean, as may consist with your dignity), or give me leave to hie me back to the stricken city, there to abide with my cares.”

To whom blithely Pampinea replied, as if she too had cast off all her cares, “Well said, Dioneo, excellent well; gaily we mean to live; ’twas a refuge from sorrow that here we sought, nor had we other cause to come hither. But, as no anarchy can long endure, I who initiated the deliberations of which this fair company is the fruit, do now, to the end that our joy may be lasting, deem it expedient that there be one among us in chief authority, honored and obeyed by us as our superior, whose exclusive care it shall be to devise how we may pass our time blithely. And so that each in turn may prove the weight of the care, as well as enjoy the pleasure, of sovereignty, and, no distinction being made of sex, envy be felt by none by reason of exclusion from the office; I propose, that the weight and honor be borne by each for a day; and let the first to bear sway be chosen by us all, those that follow to be appointed toward the vesper hour by him or her who shall have had the signory for that day; and let each holder of the signory be, for the time, sole arbiter of the place and manner in which we are to pass our time.”

Pampinea’s speech was received with the utmost applause, and she was chosen queen for the first day. Whereupon Filomena hied her lightly to a bay tree, having often heard of the great honor in which its leaves—and such as were deservedly crowned therewith—were worthy to be held. Having gathered a few sprays, she made a wreath of honor and set it on Pampinea’s head. The wreath was thenceforth, while their company endured, the visible sign of the wearer’s sway and sovereignty.

No sooner was Queen Pampinea crowned than she bade all be silent. She then summoned the four maids and the servants of the three young men and said to them, “That I may show you all at once how our company may flourish and endure as long as it shall pleasure us, with order met and assured delight and without reproach, I first of all constitute Dioneo’s man, Parmeno, my seneschal and entrust him with the care and control of all our household, and all that belongs to the service of the hall. Pamfilo’s man, Sirisco, I appoint treasurer and chancellor of our exchequer; and be he ever answerable to Parmeno. While Parmeno and Sirisco are too busy about their duties to serve their masters, let Filostrato’s man, Tindaro, have charge of the chambers of all three. My maid, Misia, and Filomena’s maid, Licisca, will keep in the kitchen, and with all due diligence prepare such dishes as Parmeno shall bid them. Lauretta’s maid, Chimera, and Fiammetta’s maid, Stratilia, we make answerable for the ladies’ chambers, and wherever we may take up our quarters, let them see that all is spotless. And now we enjoin you, one and all alike, as you value our favor, that none of you, go where you may, return whence you may, hear or see what you may, bring us any tidings but such as be cheerful.”

These orders thus succinctly given were received with universal approval. Whereupon Pampinea rose, and said gaily, “Here are gardens, meads, and other places delightsome enough, where you may wander at will and take your pleasure; but on the stroke of tierce,1 let all be here to breakfast in the shade.”

Thus dismissed by their new queen, the gay company sauntered gently through a garden, the young men saying sweet things to the fair ladies, who wove fair garlands of diverse sorts of leaves and sang love songs.

Having thus spent the time allowed them by the queen, they returned to the house, where they found that Parmeno had embraced his role with zeal. In a hall on the ground floor they saw tables covered with the whitest of cloths, beakers that shone like silver, and sprays of broom scattered everywhere. So, at the bidding of the queen, they washed their hands, and all took their places as marshaled by Parmeno. Daintily prepared dishes were served, and the finest wines were at hand; the three servingmen did their office noiselessly. All was fair and ordered in a seemly manner. The spirits of the company rose, and they seasoned their viands with pleasant jests and sprightly sallies. Breakfast done, the tables were removed, and the queen bade fetch instruments of music; all, ladies and young men alike, knew how to tread a measure, and some of them played and sang with great skill. So, at her command, Dioneo having taken a lute and Fiammetta a viol—and with the servants dismissed to their repast—they struck up a dance in sweet concert. The queen, attended by the other ladies and the two young men, led off a stately carol, which segued into a singalong of ditties dainty and gay. Thus they diverted themselves until the queen, deeming it time to retire, dismissed them all for the night. So the three young men and the ladies withdrew to their quarters, which were in different parts of the palace. There they found the beds well made and an abundance of flowers. They undressed and went to bed.

Shortly after three pm the queen rose and roused the rest of the ladies, as well as the young men, averring that it was injurious to health to sleep long in the daytime. They hied to a meadow where the grass grew green and luxuriant, being nowhere scorched by the sun, and a light breeze gently fanned them. At the queen’s command they arranged themselves in a circle on the grass, and hearkened while she spoke:

“You mark that the sun is high, the heat intense, and the silence unbroken save by the cicadas among the olive trees. It would be the height of folly to quit this spot at present. Here the air is cool and the prospect fair, and here are dice and chess. Take, then, your pleasure; but, if you take my advice, you will find pastime for the hot hours before us not in play, in which the loser must needs be vexed, and neither the winner nor the onlooker much the better pleased, but in telling of stories, in which the invention of one may afford solace to all the company of his hearers. You will not each have told a story before the sun dips and the heat abates, so we can go and take our pleasure where it may seem best to each. If my proposal meets with your approval—for in this I am disposed to consult your pleasure—let us adopt it; if not, divert yourselves as best you may, until the vesper hour.”

The queen’s proposal being approved by all, ladies and men alike, she added, “So please you, then, I ordain, that, for this first day, we be free to discourse of such matters as most commend themselves, to each in turn.” She then addressed Pamfilo, who sat on her right hand, bidding him with a gracious air to lead off with one of his stories. And prompt at the word of command, Pamfilo, while all listened intently, thus began.

1 A canonical hour meaning nine am. ↩

Read the other entries in our series: Heinrich Heine, George Eliot, Samuel Pepys, Willa Cather, Lucretius, Thomas Mann, Jack London, John Keats, Alessandro Manzoni, Frances Hodgson Burnett, Daniel Defoe, François Rabelais, and Robert Louis Stevenson.