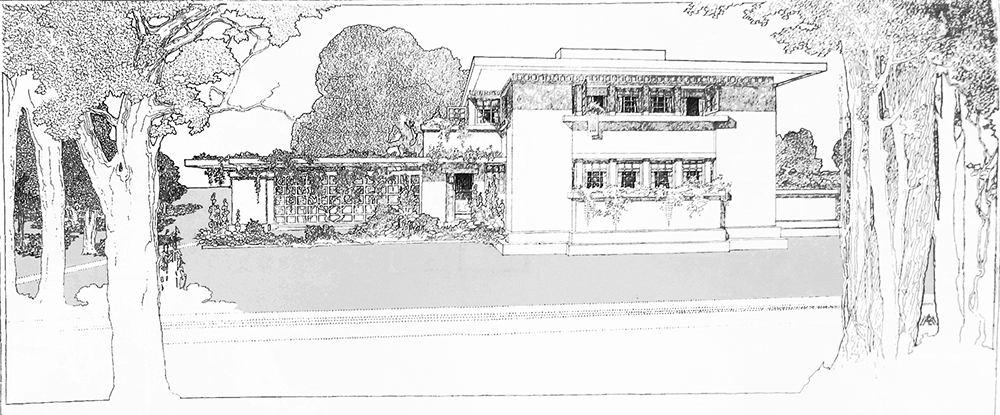

Illustration from Ladies’ Home Journal, February 1948. Wikimedia Commons, Internet Archive.

In the 1890s, empire building was in the air in New York, and magazine editors succumbed to the craze. As President Theodore Roosevelt sent troops to Cuba and the Philippines, the magazine men—they were nearly all men—had quieter plans to extend their influence. They used their brands to sell model homes, universities, and other offerings of middle-class life. It was, after all, the Progressive Era, when technological innovations and post-Victorian values were supposed to hasten the arrival of a more enlightened, egalitarian social order. Before the concept of branding even existed, these new magazine ventures represented an exercise in branding. But woven into this phenomenon lay a stealth traditionalism, a new way of packaging the often conservative, sometimes quixotic visions of a few titans of the press.

Editors Edward Bok (Ladies’ Home Journal), John Brisben Walker (Cosmopolitan), and S.S. McClure (McClure’s) saw a way to directly shape their readers’ class aspirations. In 1895 Ladies’ Home Journal began to offer unfrilly, family-friendly architectural plans in its pages. They were mainly colonial, Craftsman, or modern ranch-style houses, and many still stand today. The Cosmopolitan, as it was then known, advertised the Cosmopolitan University, a custom-designed college degree—for free!—by correspondence course. McClure’s magazine, the juggernaut of investigative journalism—home to Ida Tarbell’s landmark investigation of Standard Oil, among many other muckraking articles of the Gilded Age—began to plot an array of ventures, including a model town called McClure’s Ideal Settlement.

Cannily noting the trend for smaller, servantless suburban homes, Journal editor Bok was selling more than home design. Every house should be occupied by a female homemaker, he decided, and every family should aspire to a simpler, more frugal way of life. The campaign rapidly succeeded. By 1916 the editors of the Journal claimed that thirty thousand of their homes had been built. Part of this was due to the Journal’s wide circulation—it was the first American magazine to surpass a million subscribers. Its sister publication, the weekly Saturday Evening Post, was a fixture of nearly every household, boosting the finances of Bok’s operation.

The Journal, as historian David Shi demonstrated in his book The Simple Life: Plain Living and High Thinking in American Culture, persistently advised readers to make do with less, publishing articles like “How We Can Lead a Simple Life, by an American Mother,” “How We Live on $1,000 a Year or Less,” “How to Live Cheaply,” “A Lesson in Plain Sewing,” “Economical Use of Left-Overs,” “What Nervous People Should Eat,” and “A Spartan Mother.” Bok was convinced that most housewives could achieve perfect fulfillment, even while he chose not to delve into the complexities of economic instability. “The woman of simplest means,” Bok contended, “is the happiest woman on earth, if she only knew it.”

Stanford White, the architect who designed the Washington Square arch in New York City, wrote shortly before his murder in 1906, “I firmly believe that Edward Bok has more completely influenced American domestic architecture for the better than any man in his generation.” White had initially refused to cooperate with Bok’s scheme, and came to regret his decision. Bok himself was satisfied if not humbled by his impact on the American suburbs. As he said once to George Bernard Shaw, the Journal’s pages provided him with the world’s “largest possible pulpit,” and he intended to make use of it to express his vision for what the American woman should be. In a Journal editorial in 1900, he decried the fact that women “are today slaves of their homes and what they have crowded into them.” His idea, he noted separately, was to keep women in the home—but to change that context so drastically that it replaced a sense of bondage with contentment.

There was a need for a new perspective on the domestic sphere, though maybe one more aimed at efficiency than deprivation. General housekeeping was a depleting cycle of difficult and time-consuming tasks. Monday might be fully given over to scrubbing and wringing out laundry, Tuesday was designated for ironing, and so on. Meals needed to be prepared and rooms needed to be tidied daily, not to mention small children underfoot. If an architect could design a house with the needs of the homemaker in mind, such a product was bound to become an object of desire. The plans eventually included designs by Frank Lloyd Wright, in the prairie style with an open floor plan and strong horizontal lines, and a so-called Fireproof House, built of concrete with wide overhanging eaves. The plans were a steady feature of the magazine until 1919, when Bok formally retired. Later editors didn’t share his preference for running investigative articles alongside domestic guidance, and the magazine became more strictly aimed at homemakers.

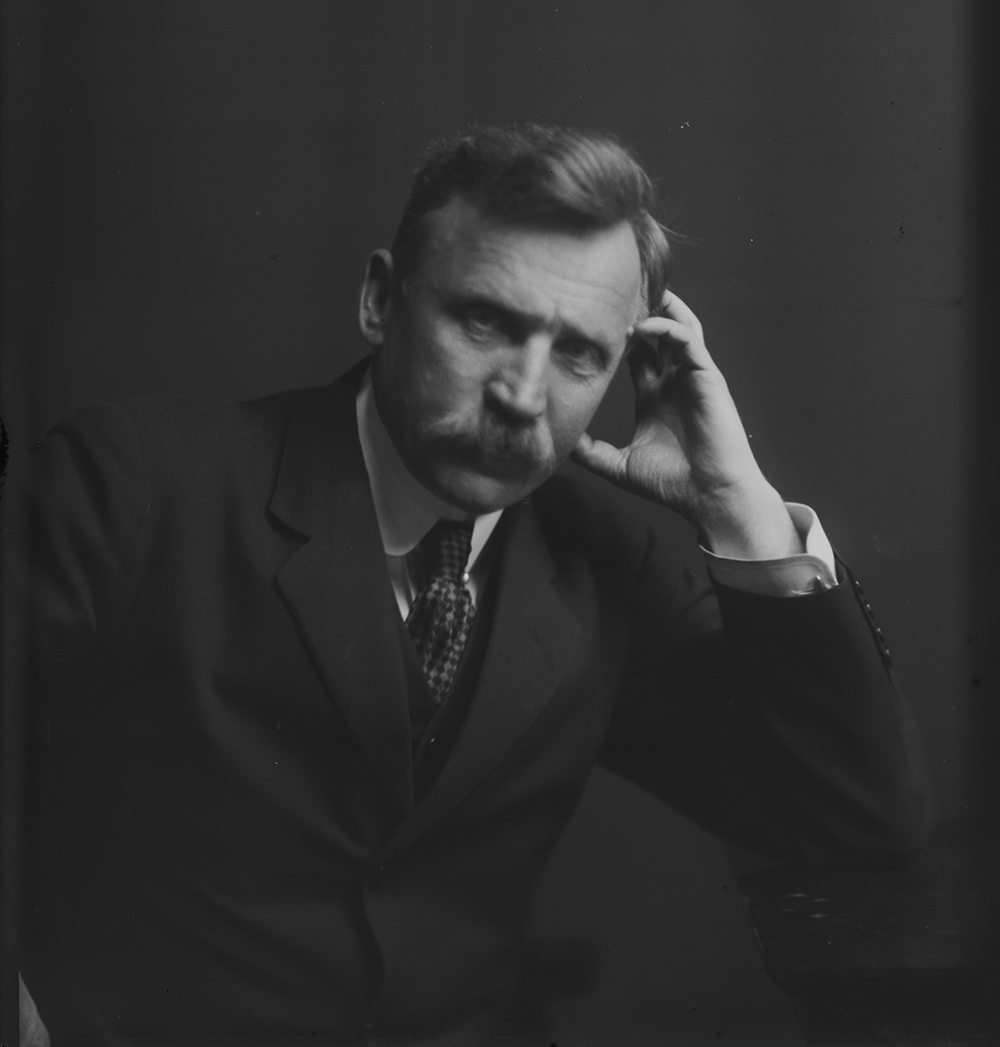

As the first Journal houses were advertised, a rival magazine made a different kind of claim on readers’ aspirations. Cosmopolitan editor John Brisben Walker, a former alfalfa king of Colorado, had the kind of mind that leaped quickly from interest to obsession. His vision for The Cosmopolitan embraced the magazine’s preeminence as a source of news, entertainment, and consumer manipulation in the pre-radio age. The motto he designated for his magazine was startlingly Marxist: “From Every Man According to His Ability: To Every One According to His Needs.”

Today, the idea of a school run by Cosmopolitan magazine might suggest an intense course of study on what he really wants. At the turn of the twentieth century, however, the magazine was a respected general-interest monthly, home to wide-ranging journalism, criticism, and fiction by Arthur Conan Doyle and H.G. Wells, among others. In his September 1897 announcement of Cosmopolitan University, Walker outlined its mission, and the venture had grandiose ambitions: “The Cosmopolitan has represented from the beginning the belief that, with the closing of the nineteenth century, the human race is destined to make rapid strides toward a new and higher civilization. Every great periodical, by fearlessly championing the cause of justice and reason, has the power to advance the time when all may enjoy greater prosperity and, with the development of higher intellectual powers in the right directions, greater happiness.”

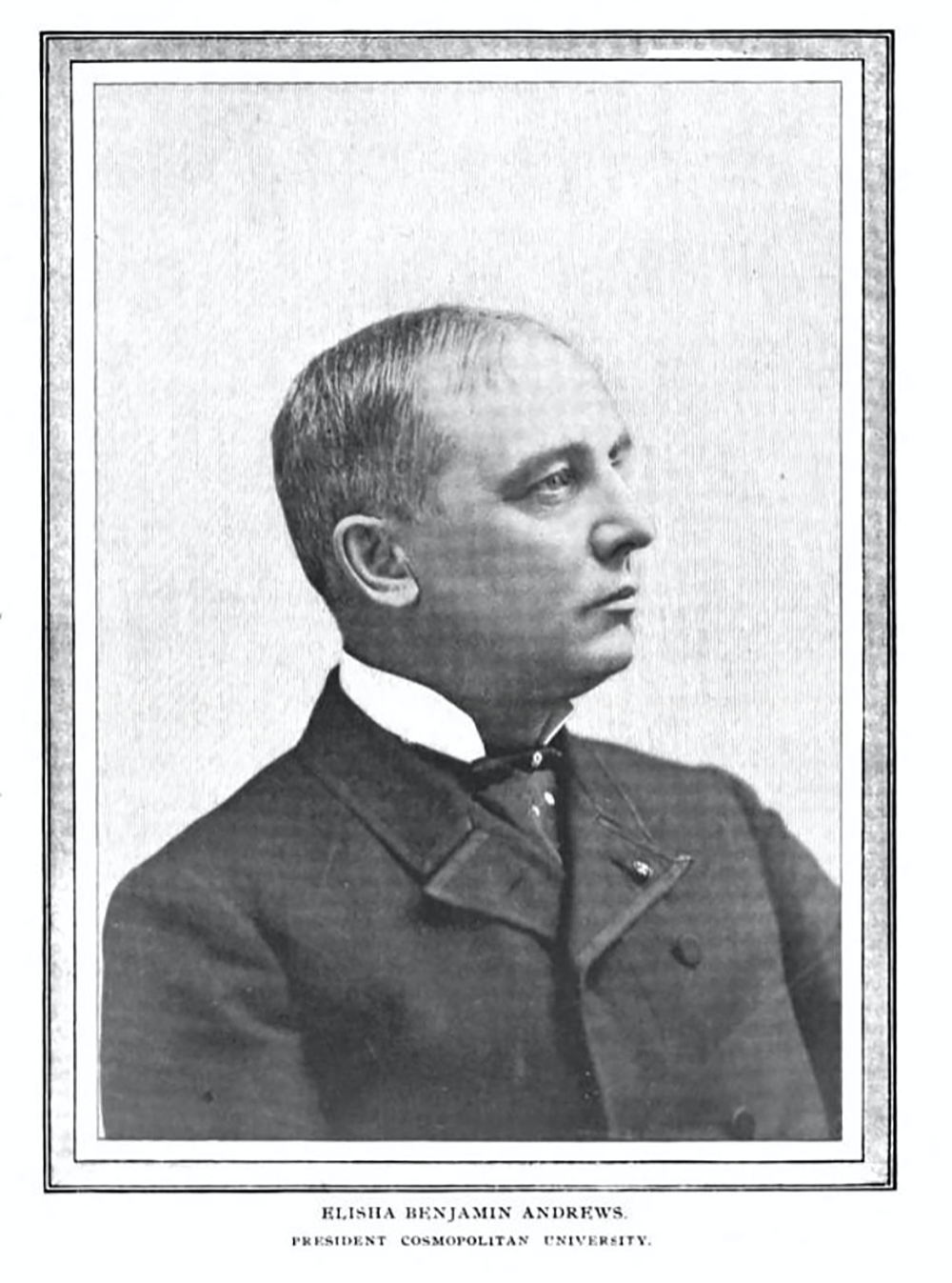

Where Bok’s watchword was simplicity, Walker’s was modernity. He saw the old Eastern universities as antiquated and exclusive, and modeled his own university on Chautauqua Institution courses, which sprang out of the era’s popular Methodist summer gatherings on Chautauqua Lake in western New York State. Initially an extension of a family-oriented Sunday school program, the courses evolved to offer comprehensive adult education by correspondence. He recruited former Brown University president Elisha Benjamin Andrews, decided tuition and materials would be free, and waited for applications to land.

The Cosmopolitan had already demonstrated an affinity for thinking big. When the New York World announced Nellie Bly’s attempt to circumnavigate the world in eighty days in 1889, Walker hastily sent his magazine’s book reviewer, Elizabeth Bisland, to race Bly in the opposite direction. According to James Landers’ biography of the magazine, towns on major train lines were liable to see Cosmopolitan train cars festooned with banners promoting the magazine. Subscription hawkers were incentivized by a special prize: the top thousand sellers were awarded sponsored college education to Georgetown, Harvard, Michigan, Vassar, Wellesley, or Yale.

The launch of Cosmopolitan University was met with earnest enthusiasm from readers—and a touch of mockery from eminent critics. Seven hundred applications had arrived within two weeks of the announcement, and by May 1898 the office had received 18,854 applications from men and women across the country. Influential figures such as Adolph Ochs, publisher of the New York Times, laughed at Walker’s model. “Is there any insuperable obstacle to the establishment of an institution of liberal education in connection, say, with a restaurant?” read an editorial. One course of study ought to be “the most liberal instruction in the science of the proper adjustment of sandwich to beverage.”

As it turned out, the most idealistic aspect of Walker’s plan was its downfall. If Cosmopolitan University were to serve all applicants without charge, the magazine would go bankrupt. Though the project was never supposed to make money—instead, it represented an idealistic leap based on a Progressive notion about the value of broad education, as well as a way to extend the magazine’s reputation—Walker hadn’t reckoned on such demand. Just as this was starting to become evident, university president Andrews abandoned the enterprise and returned to Brown. Soberly, Walker announced a tuition fee of $5 per student. Enough applicants paid to justify the employment of three Cosmopolitan University professors through the early 1900s. Eventually the gleam in Walker’s eye shifted, first to aviation, then to the automobile. (Ochs’ New York Times also mocked Walker’s interest in air travel, a “common fad” closer to “airy persiflage” than real possibility.) In 1906 Walker sold The Cosmopolitan to publisher William Randolph Hearst, whose preoccupation with politics transformed the magazine into a vehicle for sensational investigative journalism.

A third magazine, McClure’s, already encompassed a syndicate and book-publishing department, besides its renowned team of reporters and editors. But editor S.S. McClure dreamed of a second magazine, perhaps even a daily newspaper. When he finally wrote his prospectus for an extension of the McClure’s brand, he seemed unable to settle on one idea. Instead, he envisioned a bank, an insurance company, and “McClure’s Ideal Settlement”—an entire town probably based on model towns like Pullman, Illinois. Built by industrialist George Pullman to house workers at his railcar company, the town of Pullman offered homes with modern conveniences like indoor plumbing but required residents to adhere to a code of good behavior.

The new prospectus also included “McClure’s People’s University,” which would provide a curriculum via mail and publish its own textbooks, also based on the Chautauquan model, though probably not for free. It was too much at once for a magazine that had made its name with painstaking investigative series and literary discoveries. When McClure’s staff read the prospectus in early 1906, the core group of reporters and editors resigned together rather than try to make their editor’s vision a reality. The walkout made for eager gossip and a wave of headlines in the New York media world, and McClure’s limped onward until it was bought by Hearst in the 1920s and ultimately restyled as a women’s magazine. It folded soon thereafter. Readers never knew of McClure’s hopes until his former staff published their memoirs decades later. Perhaps of the three editors, Hearst was the only one who successfully expanded his influence from publishing to national politics, using his clout in each sphere to boost the other.

The grandiosity of these ideas required a certain minimum of power that editors today do not possess. Though not every editor saw his ambitions fulfilled, these three forays show how magazines first experimented with their sway over readers’ tastes, dreams, and buying habits. In the interwar period the salesmanship became even more brash—probably because print had lost its dominant status. Harper’s Bazar (as it was then spelled) advertised gift packages curated by the editors and Parisian shopping itineraries designed by their expat fashion expert. Today we might be affected by the same hunger for a product endorsed by Better Homes & Gardens, the Wirecutter, or Young House Love.

But what would we be seeing if making a profit were less of a burden? What if media tastemakers had, once again, a measure of financial and reputational influence to bet on visions of the future? Today entrepreneurial rather than editorial innovation suggests an answer: Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos’ ten-thousand-year clock and spaceport, for example. Alternatively, branding feeds more branding until the point of collapse, as was the case of Trump University or the Fyre Festival.

Samir Husni, professor and director of the Magazine Innovation Center at the University of Mississippi, points out that until the 1950s, magazines were the only national—even international—marketing medium; newspapers and radio tended to be more local. If one of the big women’s magazines promoted a specific style of home design or educational program, thousands of believers instantly appeared. Similarly, if they ran ads for one product over another, trusting buyers would open their checkbooks.

Magazines were, in Husni’s words, “reflectors of society, as well as initiators.” The same can be said for their inheritors, though these now take virtual and ever-shifting forms.