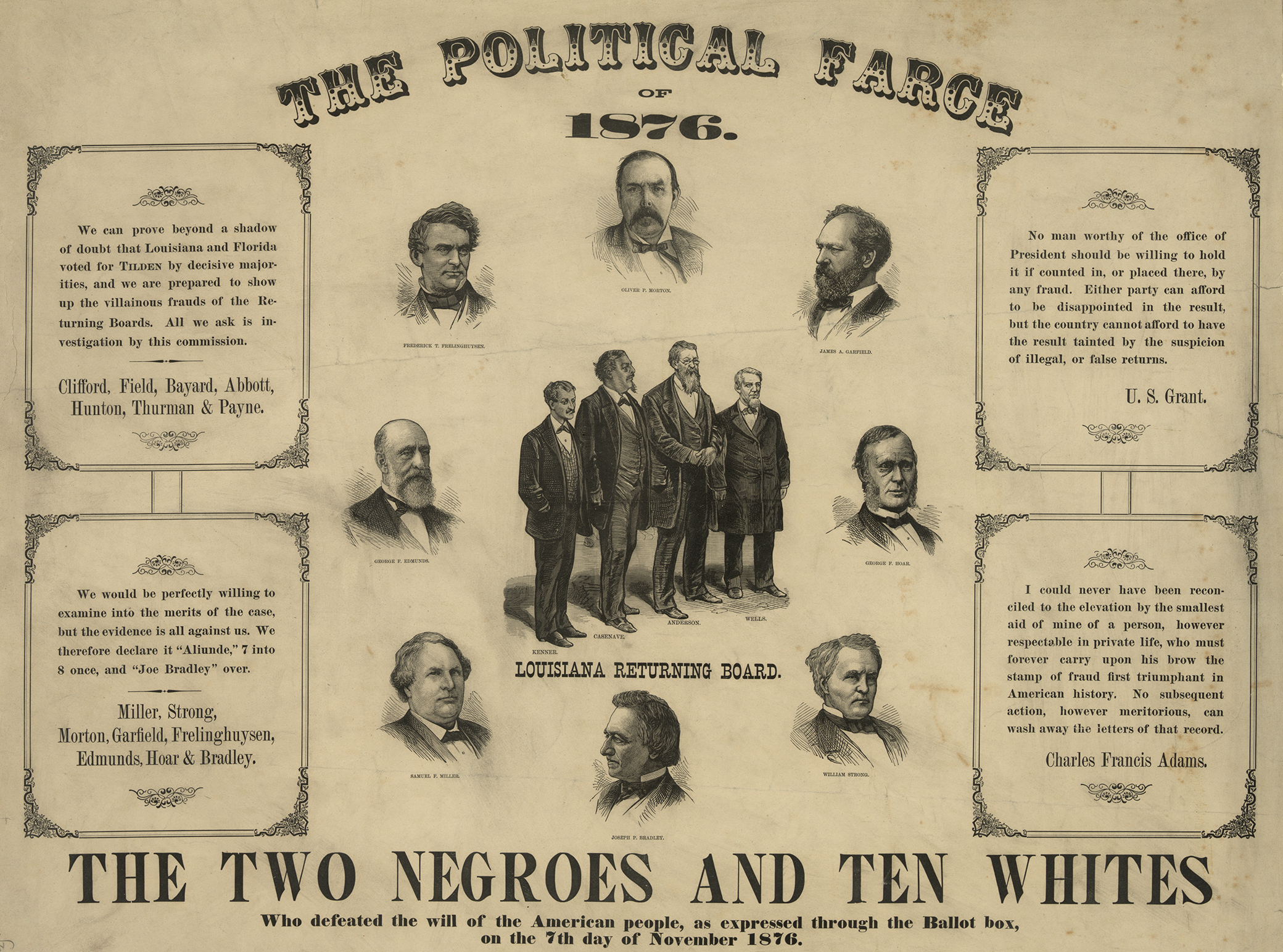

The Political Farce of 1876, published by Joseph A. Stoll, c. 1877. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

During the 2020 U.S. presidential election season, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories of those who got out the vote, narrated trips to the polls, tested the limits of their political power, cheated their way to an electoral victory, or were prevented from exercising any of these democratic roles by the actions of their leaders or neighbors.

The presidential election of 1876 marked the second time that the declared victor did not win the popular vote—an event that has occurred only five times in U.S. history. Ulysses S. Grant, plagued with scandals, had decided not to run for a third term; the Republicans chose, without enthusiasm and with much deliberation, a compromise candidate: Ohio governor Rutherford B. Hayes. New York governor Samuel J. Tilden led the Democratic ticket.

Hayes was one of the rare presidents who kept a diary of his time in office and long thereafter. His October and November 1876 entries convey the deep uncertainty of the moment. He seemed quite certain of his campaign’s failure as the votes were being counted, but he also was aware that if the results were close, the outcome could be a mess. “Another danger is imminent—a contested result,” Hayes wrote in his diary on October 22. “And we have no such means for its decision as ought to be provided by law. This must be attended to hereafter. We should not allow another presidential election to occur before a means for settling a contest is provided.”

He did not yet know that his opponent would become the only person destined to win an outright majority of the popular vote—50.9 percent—and still lose the election. Congress created a fifteen-member Electoral Commission to sort out the disputed Electoral College votes that would determine the winner. It did not sort out anything to the satisfaction of all parties involved. Eventually the Democratic and Republican Parties came to a compromise in early 1877, as inauguration day neared: Hayes would be recognized as president if the Republicans vowed to recall the last remaining federal troops stationed in the South. The federal government’s commitment to Reconstruction was now wiped off the map—after an election that had seen white supremacist organizations violently suppress Republican turnout across the South.

“I can retire to public life,” Tilden reportedly said afterward, “with the consciousness that I shall receive from posterity the credit of having been elected to the highest position in the gift of the people, without any of the cares and responsibilities of the office.”

But all of this was yet to come in the cold days of November 1876, when election returns were still coming in well after November 7 and everything was up in the air.

Saturday, November 11

The election has resulted in the defeat of the Republicans after a very close contest. Tuesday evening a small party assembled in our parlor to hear the news. The first dispatch was from Rutherford [Hayes’ son, a student at Cornell University], showing a majority in Ithaca, New York, and a gain over Grant in 1872. We all felt that the state of New York would decide the contest. Our last dispatches from our committee in New York were very encouraging—full of confidence.

Mr. A.B. Cornell, chairman of the New York State Committee, said in an experience of ten years he had never seen prospects brighter on the eve of an election. But we all knew—warned by the enormous registration in the cities of New York and Brooklyn and other facts—that we must not count confidently on carrying the state. The good omen from Ithaca was accepted with a quiet cheerfulness.

Almost at the same instant came a gain of thirty-six in Ballville, the township nearest my own home. This was good. Then came, one at a time, towns and precincts in Ohio. The comparison was made with the vote in 1875, instead of with the vote of October last. This was confusing. But soon we began to feel that Ohio was not doing as well as we had hoped. The effect was depressing. I commanded without much effort my usual composure and cheerfulness. Lucy [his wife] felt it more keenly. Without showing it, she busied herself about refreshments for our guests and soon disappeared. I found her soon after abed with a headache. I comforted her by consoling talk; she was cheerful and resigned, but did not return to the parlor. Without difficulty or much effort I became the most composed and cheerful of the party.

We heard that in some two hundred districts of New York City, Tilden had about a twenty thousand majority, which indicated fifty thousand in the city. The returns received from the rural districts did not warrant the belief that they would overcome such a large city majority. From that time, I never supposed there was a chance for Republican success.

I went to bed at twelve to one o’clock. Talked with Lucy, consoling her with such topics as readily occurred of a nature to make us feel satisfied on merely personal grounds with the result.

We soon fell into a refreshing sleep and the affair seemed over. Both of us felt more anxiety about the South—about the colored people especially—than about anything else sinister in the result. My hope of a sound currency will somehow be realized; civil-service reform will be delayed; but the great injury is in the South. There the amendments will be nullified, disorder will continue, prosperity to both whites and colored people will be pushed off for years.

But I took my way to my office as usual Wednesday morning, and was master of myself and contented and cheerful. During the day the news indicated that we had carried California; soon after, other Pacific states; all New England except Connecticut; all of the free states west except Indiana; and it dawned on us that with a few Republican states in the South to which we were fairly entitled, we would yet be the victors.

From Wednesday afternoon the city and the whole country has been full of excitement and anxiety. People have been up and down several times a day with the varying rumors. Wednesday evening on a false rumor about New York, a shouting multitude rushed to my house and called me out with rousing cheers.

I made a short talk, saying [as reported by the papers]: “Friends: If you will keep order for one half minute, I will say all that is proper to say at this time. In the very close political contest, which is just drawing to a close, it is impossible, at so early a time, to obtain the result, owing to the incomplete telegraph communications through some of the southern and western states. I accept your call as a desire on your part for the success of the Republican party. If it should not be successful, I shall surely have the pleasure of living for the next year and a half among some of my most ardent and enthusiastic friends, as you have demonstrated tonight.”

From that time, the news has fluctuated just enough to prolong the suspense and to enhance the interest. At this time the Republicans are claiming the election by one electoral vote.

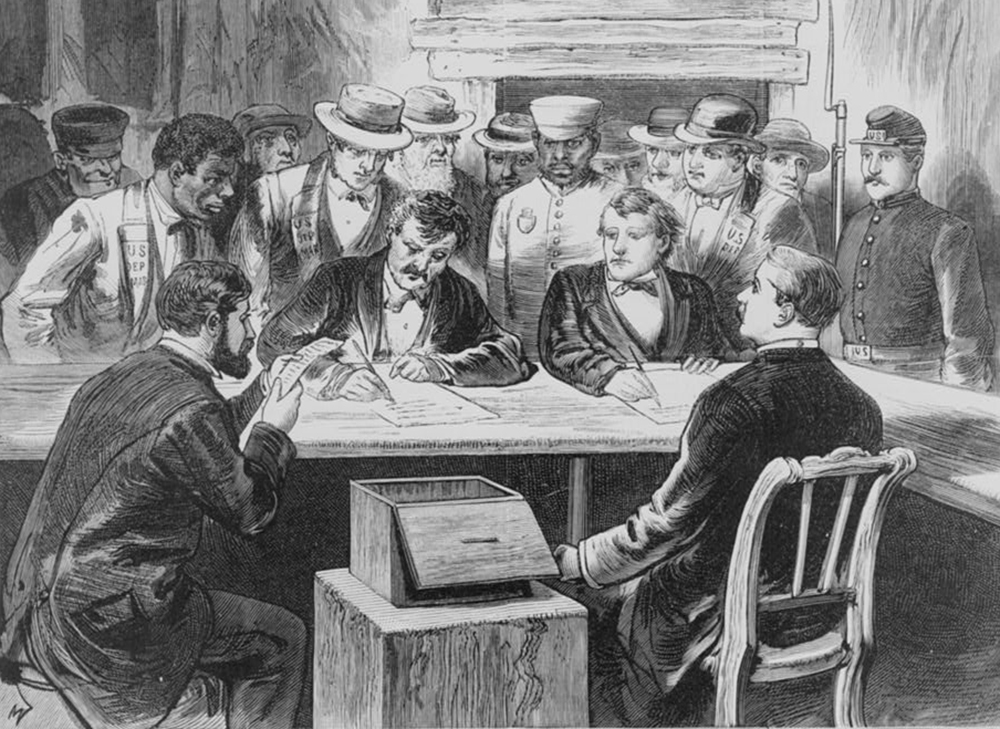

With Louisiana, South Carolina, and Florida, we have carried 185 electoral votes. This creates great uneasiness. Both sides are sending to Louisiana prominent men to watch the canvassing of the votes.

All thoughtful people are brought to consider the imperfect machinery provided for electing the president. No doubt we shall, warned by this danger, provide, by amendments of the Constitution or by proper legislation, against a recurrence of the danger.

Sunday, November 12

The news this morning is not conclusive. The headlines of the morning papers are as follows:

The News, nip and tuck; tuck has it; the mammoth national doubt. The Herald heads its news column, which? But to my mind the figures indicate that Florida has been carried by the Democrats.

No doubt both fraud and violence intervened to produce the result. But the same is true in many southern states.

We shall, the fair-minded men of the country will, history will hold that the Republicans were by fraud, violence, and intimidation, by a nullification of the Fifteenth Amendment, deprived of the victory which they fairly won. But we must, I now think, prepare ourselves to accept the inevitable. I do it with composure and cheerfulness. To me the result is no personal calamity.

I would like the opportunity to improve the civil service. It seems to me I could do more than any Democrat to put southern affairs on a sound basis. I do not apprehend any great or permanent injury to the financial affairs of the country by the victory of the Democrats. The hard-money wing of the party is at the helm. Supported, as they should be and will be, in all wise measures, by the great body of the Republican Party, nothing can be done to impair the national credit or debase the national currency. On this, as on all important subjects, the Republicans will still hold a commanding position.

We are in a minority in the Electoral College; we lose the administration. But in the former free states—the states that were always loyal—we are still in a majority. We carry eighteen of the twenty-two and have a two hundred thousand majority of the popular vote. In the old slave states, if the recent amendments were cheerfully obeyed, if there had been neither violence nor intimidation nor other improper interference with the rights of the colored people, we should have carried enough southern states to have held the country and to have secured a decided popular majority in the nation. Our adversaries are in power, but they are supported by a minority only of the lawful voters of the country. A fair election in the South would undoubtedly have given us a large majority of the electoral votes, and a decided preponderance of the popular vote.

I went to church and heard a good, strong, sensible sermon. After church and dinner I rode out to Alum Creek and around past the place of my old friend Albert Buttles. We talked of the presidential question as settled, and found it in all respects well for me personally that I was not elected.

November 30, 1876. Thanksgiving

The presidential question is still undecided. For more than two weeks it has seemed almost certain that the three doubtful states would be carried by the Republicans. South Carolina is surely Republican. Florida is in nearly the same condition, both states being for the Republicans on the face of the returns, with the probability of increased majorities by corrections. Louisiana is the state which will decide. There is no doubt that a very large majority of the lawful voters are Republicans. But the Democrats have endeavored to defeat the will of the lawful voters by the perpetration of crimes whose magnitude and atrocity has no parallel in our history. By murder and hellish cruelties, they at many polls drove the colored people away, or forced them to vote the Democratic ticket. It now seems probable that the returning board will have before them evidence which will justify the throwing out of enough [votes] to secure the state to those who are lawfully entitled to it.

Thanksgiving dinner and evening at [his niece] Laura’s. A happy time.

Read the previous entries in the series: Andrew Dickson White, John Milton, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Sydney Smith, and George O. Dunnell.