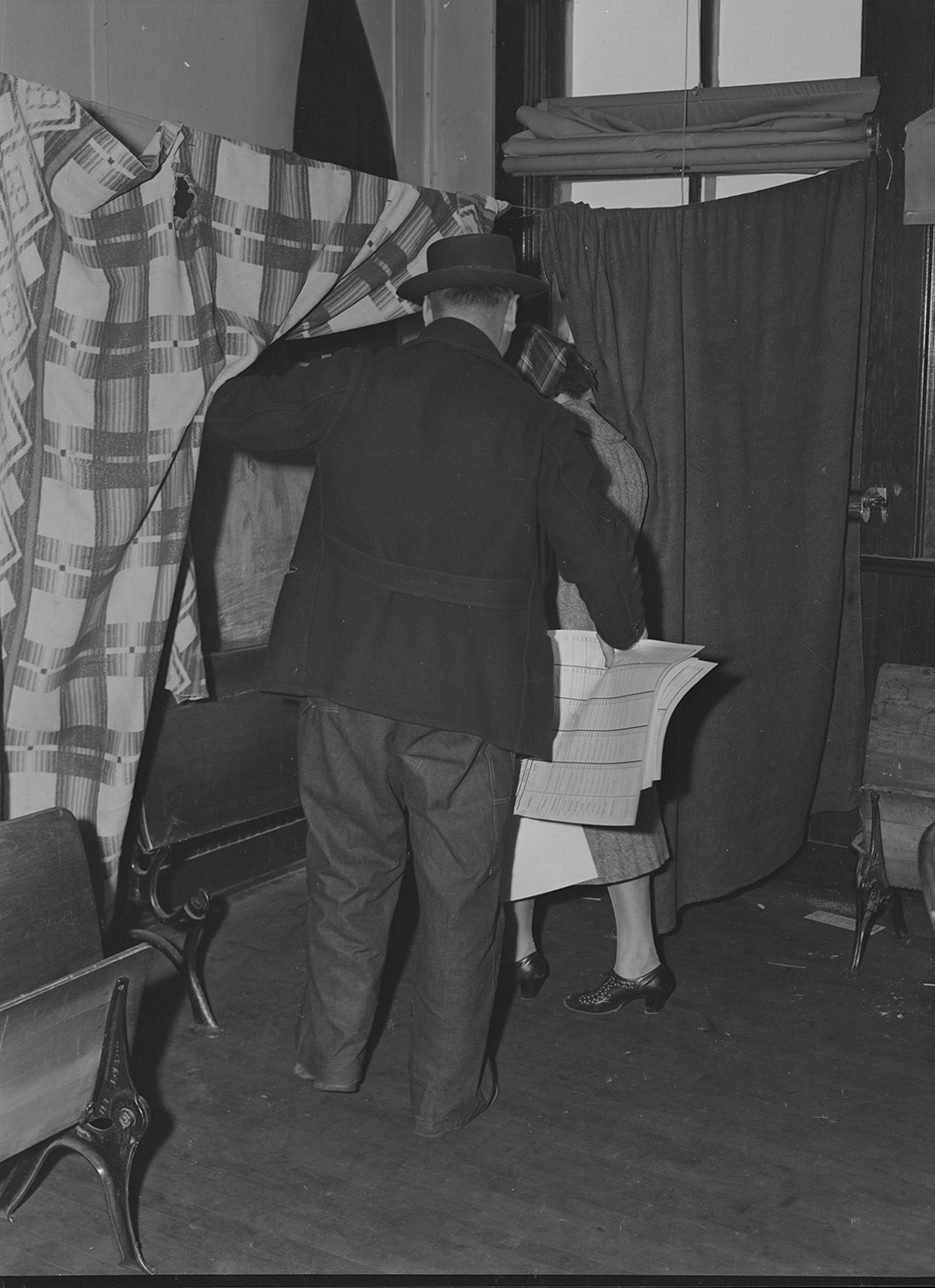

Farmer and his son on Election Day in Stem, North Carolina, 1940. Photograph by Jack Delano. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

During the 2020 U.S. presidential election season, we will feature voices from the past who told stories that rhyme with the one unfolding before us—stories of those who got out the vote, narrated trips to the polls, tested the limits of their political power, cheated their way to an electoral victory, or were prevented from exercising any of these democratic roles by the actions of their leaders or neighbors.

In the winter of 1938 Robert Wilder, on assignment with the Federal Writers’ Project, spoke to George O. Dunnell in Northfield, Massachusetts. Dunnell was a local politician and purveyor of hay, grain, and coal known by the initials G.O.D. (He bristled when other people brought up his implied divine connections but often wrangled the detail into his own stories.) Wilder described him as “a loud-voiced, rough, and heavy individual until he is faced with the necessity of appearing in public. Then he’s as quiet as a lamb and twice as shy.”

In one of their many conversations, Dunnell—who became quite voluble when gifted a man tasked with transcribing everything he said—relayed a parable concerning the importance of voter outreach, set during a local woman’s underdog campaign for town clerk.

Guess it was before you come to town the first time it come out a tie. Then we had another election—a special election—just to decide the tie. And that’s where the fun was.

You see, Charlie Stearns thought he owned the town clerk’s job because his father had it or somethin’. And some of us thought it was about time for a change. Stearns had been clerk for years, and he didn’t need the money. He is one of the kind that think they are getting ahead if they are piling up money in the bank instead of making some use of it themselves—goin’ to Floridy once in a while or doing something, by God, instead of buying books with figures in ’em from banks. First thing he knows a president or somebody will come along and say that as the rich people had won all the money and the rest of us had to keep playing the game, whether we liked it or not, that hereafter we wouldn’t use money no more. That we’d use poker chips, or pins, or buttons. And if anyone was caught selling anything for money they’d be shot!

If that happened, where would Charlie Stearns be? Anyway, we figured that Charlie Stearns had money enough without the town helping him out. And there was a nice woman here that was having a tough time. She used to keep books in a whip factory over at Hoosick Falls, and after that she was a stenographer at the seminary, and all the women knew her. We got more women voters than we have men voters, you know. You see, Stearns used to run a dry-goods store in the center of town. And he didn’t have any too many customers. He spent most of his time peeking out the window to see what folks was doing. You’d see somebody go in his store on town clerk’s business. You could see that easy from the drugstore steps ’cause Stearns always went to his desk—he’d tend to ’em nice and polite. Then he’d watch them out of sight. And when they’d gone he’d, perhaps, make tracks for old Warner’s house. Warner used to be in the legislature, you know, and was the boss politician of this town. Him and Stearns was so friendly that I guess they used to keep their teeth in the same glass of water. Sometimes he’d wait till he saw some other of his cronies going by, then he’d rush out and tell it to him. Used to make us kinda sick. Maybe it was public business. But if it was, why didn’t we hear about it?

Well, our town hall was burnt up, so we had to hold our town meetings and the elections in the church. Frank Williams burnt it up—the feller that was town treasurer and put our money in a hole in the ground out west. He’d told the janitor to build a fire in the furnace for some meeting or other that he had. The janitor wouldn’t do it, for he said the insurance people said it weren’t safe till the flue had been fixed. But Frank, he knew better than the insurance people, so he fired it up himself. The town didn’t get no insurance, though. For among other things, it seems that it had slipped Frank’s mind as treasurer to keep the policy in force. God, but that fire was funny, though us taxpayers had to pay for the fun we had. First they could have put the fire out if they’d had a fire extinguisher. There was supposed to be plenty of extinguishers around the hall. But it seems one of the selectmen had taken ’em down to his garage to recharge ’em. The gang rushed down there hellety-whoop. Nobody knew anything about ’em. Maybe they were in a locked-up place where the old man might a dumped ’em. But he’d gone off somewhere with the key. And they hadn’t been charged yet anyway.

When the gang got back to the fire, it had spread somethin’ awful. It had got to the part where the town kept its fire apparatus. But they managed to save the hose cart and a few lengths of hose. They rushed this around to a hydrant, and a feller took a wrench to turn on the hydrant. But he didn’t know which way to turn. So another feller grabbed hold with him, and between ’em, they twisted the dumb thing clean off. Guess it must a been rusted a bit. Well, anyway, they had a nice little fountain going as a kind of additional attraction. And they had to run their hose clean from another hydrant somewheres down on the Warwick Road. When the water finally come, it ran out of the hose, but that was about all—oh, maybe ten or twelve feet—but it kinda died, you know, just gradually subsided, ’cause the busted hydrant reduced the pressure. Honest, if that gang had stood around and done the best they could themselves, there’d a been more water.

So we lost the town hall and had to hold the elections in the church. The first election come out a tie, so for the second we scraped up every voter there was in this town. Gosh! It was a cold day, too. There was snow on the ground—plenty of it—but it had melted some, so the sidewalks and the roads were just covered with ice. I got out good and early and bought a box of cigars to take to church.

When I got there greasy little Charlie Stearns was greeting the voters as they come in with that oily smile of his and a handshake for anyone who would come near him. It felt nice and warm in there after the cold outside, so I took on the job of greeting the voters, too, and Charlie didn’t like it a bit. But we kept smirking at the voters, him on one side and me on the other. And I kept track well as I could in my head of who’d come and who hadn’t. Along in the afternoon I made up my mind that I’d better get outside, cold or no cold, and dig out some voters I thought would be for us. First place I went was right across the street. “You voted?” I asked the old feller who lived there alone.

“No,” said he, “too cold. Sit down, Dunnell, and have a glass of cider.”

“No,” I says, “much as I’d like to. But I’m over at the church and it wouldn’t be right to have ’em smell liquor on my breath. But I know you don’t like Charlie Stearns. And here you have a chance to beat him, and you won’t walk across the street. Now, I’ll tell you what. I’ve got to go other places, but when I get back to the church, you’d better let me find out you’ve voted. For if you haven’t, honest to God I’ll be back over here. And I’ll get in, even if I have to kick in the door. And I’ll take you just as you are, without no overcoat, right over there and make you vote.”

Well, he said he’d come.

Then I went up to a woman that runs a boarding house. No, she said, she couldn’t come, it was too cold. I told her how the women ought to stick together, but I didn’t get nowheres with that. She said a couple of my boys had stopped and asked her to ride down, but she had refused to go, and if she went with me they’d think she didn’t like ’em. “Look,” I says, “you remember the time I was delivering coal here, and I saw those weeny, scrawny potatoes you was cooking?” I says, “And how I brought you up a bag of good ones, and never charged you nothing?” I says, “Just a neighborly act to help you out when you needed it. And now you won’t even come and vote for me.” Well, she guessed she would go after all. And on the way down in the rig she asked me how she should vote. “Oh, I can’t tell you that!” I says, “it wouldn’t be proper. You vote just as you’ve a mind to. But I’m not ashamed to tell you how I voted.”

Well, it was just like that all the afternoon. Only thing a little out of the ordinary was in the store when I went to look for a clerk. “Fred around?” I asked the bookkeeper. She said, “Yes,” but the way she kinda colored up, I thought I knew where he was, so I went down the cellar and then out back. “Come out of that,” I yells, “come on out and vote!”

“Go away,” he says. “I ain’t got no time to vote.”

“By God, mister,” I yells, “You promise me that you’ll come over and vote just as quick as you can, or I’ll bust in the door and take you just as you are!”

He promised all right after I’d shook the door a bit.

When I got back to the church I was pretty much all in. I hadn’t had nothing to eat all day, and my box of cigars hadn’t helped my stomach any. I figured we was licked. And I had a mind to sneak off home before they got the votes counted. But I went over and over in my mind. And I couldn’t see that we’d skipped anybody. Charlie Stearns had a sagging puss on him as though he was all ready to cry, so I figured it wasn’t going to be no walkover for their side, and started shooting off my mouth about how much the town was going to benefit by a new town clerk.

The Stearns fellers didn’t like it, of course. One of ’em, Will Merriman, says, “I see you coming up by the cemetery,” he says, “getting ’em out of there you was, hey?”

I knew he’d seen me when I stopped for the Mattoon sisters, who live down that way, and who I had to help over the ice to get into the rig. They was pretty old.

“Oh no,” I says. “We didn’t get near all the voters we could have out of the cemetery. All we bothered was in the new part. We didn’t get around to tackle the old part.” After that, I begun to feel better. And I swaggered around confident as you please. But I done near died when the time come to announce the vote. Seems if I couldn’t stand it. When I heard that we’d won by one vote, I let out a yell that Stearns’ ancestors could’ve heard. I started out on a run to spread the glad tidings—and I forgot all about the ice. What is it the Bible says? Something about “pride going before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall”? I guess so.

Anyway, I had a fall all right. I slid about forty miles. And I busted my box of cigars—what they was left of ’em. But it didn’t hurt me none, ’cause we’d licked that poor, little, miserable runt of a Stearns. If we hadn’t, I’d had to have gone to the hospital, I expect.

Read the previous entries in the series: Andrew Dickson White, John Milton, Frances Ellen Watkins Harper, Sydney Smith, and Rutherford B. Hayes.