African America Civil War Memorial, 2006. Photograph by Carol M. Highsmith. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In the spring of 1890, John Mitchell, the fiery twenty-six-year-old editor of the black newspaper the Richmond Planet, made sure that his paper covered the dedication of Richmond’s majestic monument to Robert E. Lee, notable as the first heroic equestrian statue of a Confederate erected anywhere in the United States. Mitchell had been born enslaved in Richmond during the war fought by Lee and the Confederacy to keep him and his people in bondage. Shortly after the statue’s unveiling, he wrote, “The Negro…put up the Lee Monument, and should the time come, will be there to take it down.”

Remarkably, that time has now come. While Richmond’s own Monument Avenue so far has escaped the removal cranes, they have been active elsewhere across the United States. At this writing, Confederate busts, statues, obelisks, fountains, and markers have come down in a couple of dozen towns and cities in the old states of the Confederacy and even as far afield as California, Missouri, Montana, and New York. Charlottesville’s huge equestrian statues have been shrouded. The Lee and Jackson windows in Washington’s National Cathedral have been removed.

Until recently, almost no one but Mitchell had anticipated this outcome. When Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves first appeared in the 1990s, the neo-Confederate movement was still in full swing. Confederate statues were being lovingly restored and sometimes even rededicated with new ceremonies. The idea that these monuments had been designed and built to promote white supremacy was often dismissed but most of the time simply ignored. Today that idea has become mainstream, discussed in newspapers and websites and talk shows. Now the defenders of Confederate monuments have largely abandoned the ideological fight and retreated to a seemingly neutral defense of “history.” Like it or not, they say, these monuments represent “our” history. Removing them, therefore, is an act of historical “erasure.”

If there is one lesson to be learned from studying how monuments get chosen and built, it is that they most certainly do not represent history in any straightforward or responsible way. They represent the agendas, obsessions, prejudices, whims, and, occasionally, the high ideals and aspirations of those people in society who happened to have the power to erect them in public. The resulting commemorative landscapes are highly politicized, and often bizarre, assemblages of historical characters—many of whom have been long forgotten, sometimes deservedly so.

And yet these landscapes and the monuments in them have their own histories that are enormously revealing and absolutely worth studying. Even if monuments pretend to be permanent, eternal, and static—in other words, outside history—they have always been prey to the historical forces that gave them birth, changed the world around them, and sometimes even destroyed them.

A crucial piece of this history, often overlooked, is the monuments that might have been but never came to be. At one time these were ideas, seeds, and sometimes elaborately developed schemas for alternative histories. They held possibilities that were later erased by the very success of those monuments that managed to rise in their stead, as Lee did on Monument Avenue.

The suppression of those alternative monuments—that parallel universe of possibility—amounted to nothing less than a preemptive erasure of the past. In the wake of the Civil War, with the United States abruptly and unexpectedly free of slavery, the nation had a unique opportunity to retell its past: to reckon with the crime of slavery, to honor the formerly enslaved people in the story of their own liberation, and to make room for them, finally, as full-fledged and necessary participants in the moral awakening of America. In the main, none of this came to pass; the commemorative landscape took an entirely different turn. It was a failure of artistic imagination and of political will, a failure at all levels to relinquish the hold of white supremacy. And that was a tragedy as well, because the erasure of alternative pasts is also, always, an erasure of alternative futures. Monuments are as much about the future as the past.

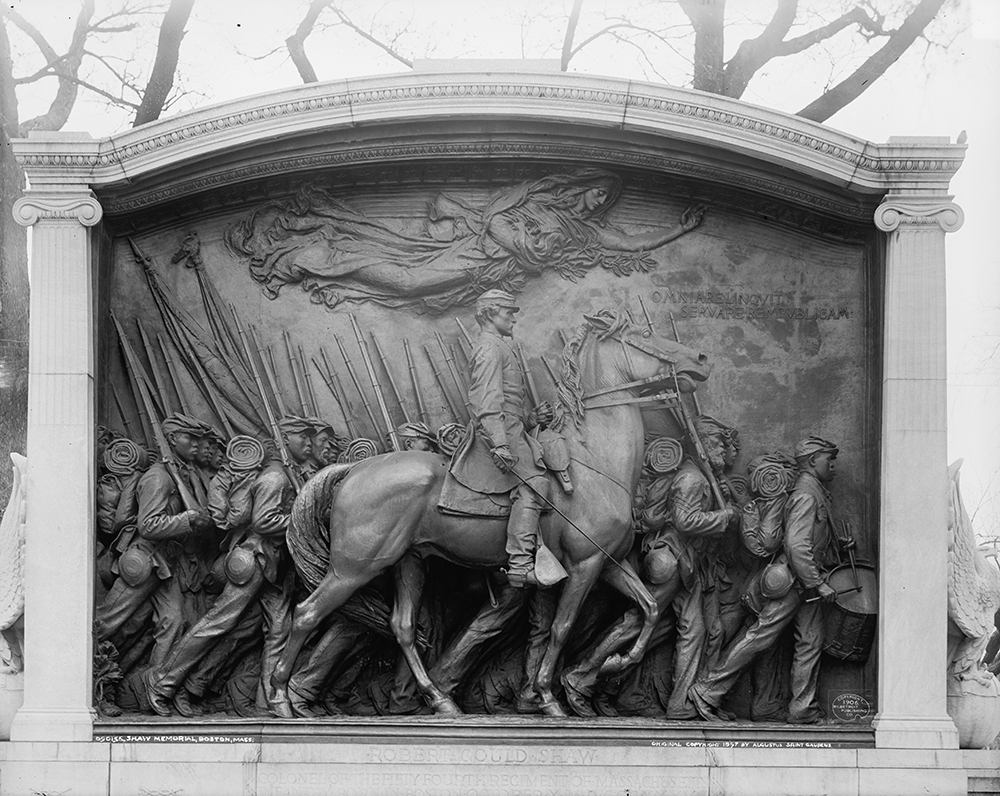

Instead the commemorative landscape became dominated by men in military uniform—not only commanders like Lee but, for the first time, ordinary anonymous soldiers, whose statues spread across the country into cities and small towns, some of which had never before had a single piece of public sculpture. Yet almost nowhere in this vast outpouring of military monuments did black soldiers get any recognition. The nearly 180,000 who enlisted in the Union Army had more at stake, and less reluctance, than anyone else in this conflict. Unlike their white counterparts, black soldiers were fighting for the most elemental cause of all, the right simply to be treated as human beings. Not until the close of the nineteenth century did a monument appear showing black soldiers in uniform—the singular memorial to Robert Gould Shaw and the 54th Massachusetts.

The march of military monuments, what William Dean Howells once derisively called a “standing army in bronze and marble,” has overtaken the Mall in Washington, DC, and the town square across the United States. This phenomenon, at one level, is a simple reflection of the immense expansion of military resources and veterans benefits in the century and a half since the Civil War. As of 2016, the U.S. military is reliably estimated to be about 300 percent more expensive than its next biggest competitor, China—a historically lopsided superiority that is hard to grasp. Yet the calls for more money and more monuments do not relent, as if the American military machine were an implacable god who can never be appeased, no matter how much sacrifice is made to it.

After World War II, in the midst of this unprecedented expansion, the U.S. armed forces were finally desegregated. War memorials began to give greater visibility to people of color. Starting with the Three Servicemen at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC (1984), the figure of the black soldier has appeared in dozens of memorials to veterans of America’s wars in Vietnam and Korea—even though the decision makers and designers in those cases are still disproportionately white.

While racial parity in representation has improved to some degree, the larger project of commemoration remains fundamentally the same, avoiding any true reckoning with the painful and problematic histories of America’s wars. The memorials of the U.S. war in Vietnam are typical: while black soldiers have been accorded a place, the Vietnamese people they fought with and against remain invisible. This absence is particularly notable given the presence of over two million Vietnamese Americans in the United States, many of them displaced directly or indirectly by the war that devastated their family’s country of origin. Yet in public space they are barely mentioned, let alone represented.

As the long conflict in Vietnam so well demonstrates, the desegregation of the U.S. armed forces in the midst of the Cold War ran parallel with American military interventions against peoples of color in poor countries across the globe that posed no credible military threat to the United States. We might well ask what racial equality means when it is yoked in this way to the ongoing project of expanding American power in the world—a project whose costs have always fallen disproportionately on noncombatants of color, who for the most part remain invisible to the majority.

This was a question that Martin Luther King Jr. pondered deeply late in his life, in the midst of the United States’ war in Vietnam. Four years after the “I Have a Dream” speech, he gave another, more somber speech, which would transform his legacy in ways that the United States has barely wrestled with. On April 4, 1967, at Riverside Church in New York he delivered a stunning moral denunciation of his own country and its perpetration of the war in Vietnam. If his earlier speech in Washington dealt with the Civil War’s unfinished promise of emancipation, the Riverside speech dealt with that war’s other legacy—the normalization of militarism.

As the speech unfolded, so did his argument that racism, poverty, and militarism were inseparable, products of a “far deeper malady of the American spirit,” which put profit over justice. He criticized much in American life, including “the Western arrogance of feeling that it has everything to teach others and nothing to learn from them.” But he saved his most devastating commentary for the sheer destructiveness of America’s war, which created the moral imperative to speak up against it:

Surely this madness must cease. We must stop now. I speak as a child of God and brother to the suffering poor of Vietnam. I speak for those whose land is being laid waste, whose homes are being destroyed, whose culture is being subverted. I speak for the poor in America who are paying the double price of smashed hopes at home, and dealt death and corruption in Vietnam. I speak as a citizen of the world, for the world as it stands aghast at the path we have taken.

At King’s monument in Washington’s Tidal Basin, this searing critique is condensed to a single quotation—not from the Riverside speech—declaring that “I oppose the war in Vietnam because I love America.” It is the only spot in the landscape of the National Mall that acknowledges the existence of an antiwar movement. But here and elsewhere in public space there is precious little recognition of the real story of dissent against America’s wars, much less anything resembling King’s profound challenge to U.S. militarism. Imagine King’s monument if it declared instead, as he did at Riverside Church, that “a nation that continues year after year to spend more money on military defense than on programs of social uplift is approaching spiritual death.”

The silences of the memorial landscape should come as no surprise. The long history of the public monument confirms their fundamental conservatism. Rarely do monuments confront the past or reckon with it. In a sense they do not deal seriously with history at all, because history is always messy and challenging and conflicted. Built by people with power and privilege, the memorial landscape usually channels their most deeply ingrained assumptions into self-justifying fables.

That deep-seated self-absorption is exactly what King prodded himself and his fellow citizens to examine and change. In the last speech he gave before his assassination in Memphis, he called on his audience to “develop a kind of dangerous unselfishness.” Invoking the parable of the Good Samaritan on the road to Jericho, King told them that he’d been on that very road. It was a dangerous, winding, meandering road, perfect for ambushes. But it was only through danger that they could “move on in these powerful days, these days of challenge, to make America what it ought to be.”

Making monuments what they ought to be will surely require a similar kind of dangerous unselfishness. The memorial landscape of the United States is filled with fossils of white supremacy and American expansionism—testaments to the very values King so powerfully renounced. To be able to live in today’s world, public monuments must get on King’s side of history and speak to the changing demographics and challenges that are affecting every community across the globe. That task is not about erasing the past but reconstructing it, to use the political term that still resonates from the late 1860s. If the United States can confront its history and reclaim the power of its lost pasts, then it can begin to imagine new futures, both for the nation and for its monuments.

Excerpted from Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America, New Edition by Kirk Savage. Copyright © 1997 by Princeton University Press. Preface to the new paperback reissue copyright © 2018 by Princeton University Press. Reprinted by permission.