Politics means a slow, powerful drilling through hard boards, with a mixture of passion and a sense of proportion. It is absolutely true, and our entire historical experience confirms it, that what is possible could never have been achieved unless people had tried again and again to achieve the impossible in this world. But the man who can do this must be a leader, and not only that, he must also be a hero—in a very literal sense. And even those who are neither a leader nor a hero must arm themselves with that staunchness of heart that refuses to be daunted by the collapse of all their hopes, for otherwise they will not even be capable of achieving what is possible today. The only man who has a “vocation” for politics is one who is certain that his spirit will not be broken if the world, when looked at from his point of view, proves too stupid or base to accept what he wishes to offer it, and who, when faced with all that obduracy, can still say “Nevertheless!” despite everything.

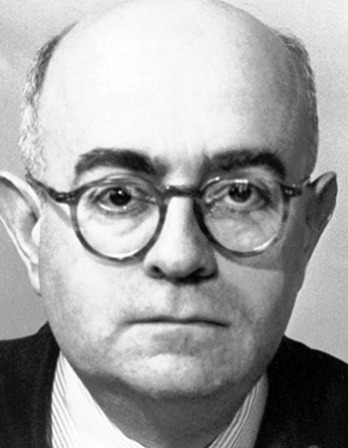

From “Politics as a Vocation.” This treatise derives from the second of two lectures on vocation, the first of which he gave on science in 1917. Writing his doctoral and postdoctoral theses on medieval trading companies and on ancient Rome’s agrarian history, respectively, Weber became a professor at the University of Berlin in 1893, suffered a nervous breakdown in 1898, and traveled to the St. Louis World’s Fair to give a lecture in 1904, the same year he began publishing The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism. He died at the age of fifty-six in 1920.

Back to Issue