The U.S. presidency is a Tudor monarchy plus telephones.

—Anthony Burgess, 1972Taking Action

Shirley Chisholm cracks the glass ceiling.

Mr. Speaker, when a young woman graduates from college and starts looking for a job, she is likely to have a frustrating and even demeaning experience ahead of her. If she walks into an office for an interview, the first question she will be asked is, “Do you type?’’

There is a calculated system of prejudice that lies unspoken behind that question. Why is it acceptable for women to be secretaries, librarians, and teachers but totally unacceptable for them to be managers, administrators, doctors, lawyers, and members of Congress.

The unspoken assumption is that women are different. They do not have executive ability, orderly minds, stability, leadership skills—and they are too emotional.

It has been observed before that society for a long time discriminated against another minority, the blacks, on the same basis—that they were different and inferior. The happy little homemaker and the contented “old darkie” on the plantation were both produced by prejudice.

As a black person, I am no stranger to race prejudice. But the truth is that in the political world I have been far oftener discriminated against because I am a woman than because I am black.

Prejudice against blacks is becoming unacceptable, although it will take years to eliminate it. But it is doomed because, slowly, white America is beginning to admit that it exists. Prejudice against women is still acceptable. There is very little understanding yet of the immorality involved in double pay-scales and the classification of most of the better jobs as “for men only.”

More than half of the population of the United States is female. But women occupy only 2 percent of the managerial positions. They have not even reached the level of tokenism yet. No women sit on the AFL-CIO council or Supreme Court. There have been only two women who have held Cabinet rank, and at present there are none. Only two women now hold ambassadorial rank in the diplomatic corps. In Congress, we are down to one senator and ten representatives.

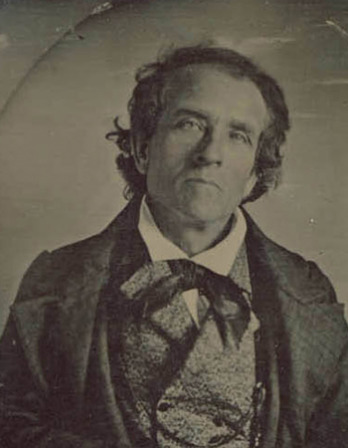

Abraham Lincoln delivering his second inaugural address, 1865. Photograph by Alexander Gardner.

Considering that there are about 3.5 million more women in the United States than men, this situation is outrageous.

It is true that part of the problem has been that women have not been aggressive in demanding their rights. This was also true of the black population for many years. They submitted to oppression and even cooperated with it. Women have done the same thing. But now there is an awareness of this situation particularly among the younger segment of the population.

As in the field of equal rights for blacks, Spanish-Americans, the Indians, and other groups, laws will not change such deep-seated problems overnight. But they can be used to provide protection for those who are most abused and to begin the process of evolutionary change by compelling the insensitive majority to reexamine its unconscious attitudes.

It is for this reason that I wish to introduce today a proposal that has been before every Congress for the last forty years and that sooner or later must become part of the basic law of the land—the Equal Rights Amendment.

Let me note and try to refute two of the commonest arguments that are offered against this amendment. One is that women are already protected under the law and do not need legislation. Existing laws are not adequate to secure equal rights for women. Sufficient proof of this is the concentration of women in lower-paying, menial, unrewarding jobs and their incredible scarcity in the upper-level jobs. If women are already equal, why is it such an event whenever one happens to be elected to Congress?

It is obvious that discrimination exists. Women do not have the opportunities that men do. And women that do not conform to the system, who try to break with the accepted patterns, are stigmatized as “odd’’ and “unfeminine.” The fact is that a woman who aspires to be chairman of the board, or a member of the House, does so for exactly the same reasons as any man. Basically these are that she thinks she can do the job and she wants to try.

A second argument often heard against the Equal Rights Amendment is that it would eliminate legislation that many states and the federal government have enacted giving special protection to women and that it would throw the marriage and divorce laws into chaos.

As for the marriage laws, they are due for a sweeping reform, and an excellent beginning would be to wipe the existing ones off the books. Regarding special protection for working women, I cannot understand why it should be needed. Women need no protection that men do not need. What we need are laws to protect working people, to guarantee them fair pay, safe working-conditions, protection against sickness and layoffs, and provision for dignified, comfortable retirement. Men and women need these things equally. That one sex needs protection more than the other is a male-supremacist myth as ridiculous and unworthy of respect as the white-supremacist myths that society is trying to cure itself of at this time.

Shirley Chisholm

“Equal Rights for Women.” The first black woman to serve in Congress, Chisholm took office as representative of New York City’s twelfth district the same year she delivered this speech. Upon winning the election she had acknowledged to a Washington Post reporter, “I am an historical person at this point, and I’m very much aware of it.” She represented her district, which covers parts of Brooklyn, Queens, and lower Manhattan, until 1982; during her tenure she became in 1972 the first woman to run in a Democratic presidential primary. Chisholm died at the age of eighty in 2005.