A functioning police state needs no police.

—William S. Burroughs, 1959

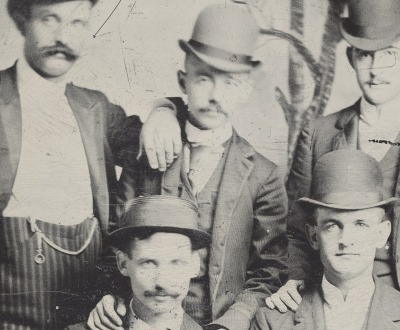

Members of the Wild Bunch, c. 1892. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, gift of the Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005.

The Italian Marxist Antonio Gramsci, jailed by Benito Mussolini in a period with fascist features not unfamiliar to us now, directed much of his attention before and after he was imprisoned to the mentality of the rural masses, or what he called “the simple people.” While alert to the cultural sway of professional intellectuals who made a living producing and propagating well-honed ideas, Gramsci insisted that the simple people were not mere living labor machines but were intellectuals, too, with concepts, values, and understandings of the world that added up to a “spontaneous philosophy of the multitude.”

Especially in times of upheaval, such as Italy’s transition from an agricultural system run by rural landowners and the Catholic Church to a capitalist industrial economy, this spontaneous philosophy was neither unitary nor consistent. It took a variety of forms in different segments of the population and in different regions of an unevenly developing country. Even in the brain of a single individual, spontaneous philosophy was typically haphazard and incoherent. Some popular ideas were imposed from without, reflecting an elite worldview that had permeated the general atmosphere via the mediation of professional intellectuals—although, with a ruling elite on the wane, these ideas were on their way to being ossified and antiquated. Other ideas took the form of superstitions and magical beliefs that translated the largely incomprehensible forces reshaping society into the repertoire of folklore. Spontaneous popular philosophy also contained strong intuitions of the illegitimacy of existing social hierarchies and inchoate desires for release from injustice.

One sign of the tectonic shift that the world is experiencing today—a shift we tend to call, for short, globalization—is a boom in popular philosophies that are even weirder and more chaotic than those of 1920s Italy. While Gramsci hoped to transform the mishmash of “common sense” into a critically scrutinized, logically coherent, and left-revolutionary “good sense,” some of the most militant attempts currently to harness popular anguish for radical purposes do so not by weeding out elements of common sense that clash with one another, misrecognize existing empirical realities, or are out of sync with emergent realities but by knitting those ill-fitting elements into a worldview with an internal mad logic all its own. This logic in turn justifies a populist revolt against the status quo not from the future-oriented left but from the past-salvaging right. Right-wing calls to arms aim their fire at global disruptions of national economies, polities, and cultures, but they sometimes target nation‑states, too, on the grounds that those states have been captured by international cabals. Such populist philosophies obscure the real causes and consequences of existing social distress at the same time that they illuminate certain truths about that distress—in the way that, at any given moment, a searchlight illuminates one small slice of the night at the cost of leaving everything else in indecipherable darkness.

Our tumultuous century has witnessed the resurgence of nationalist movements across the West that defend nation-states from so-called alien interlopers. Less widespread and less well-known are loosely organized grassroots networks that identify with their nation but see their government as entirely illegitimate. The sovereign citizens movement, which applauds the American founding but rejects the existing rule of law, is a vexing case in point. Although it has sprouted offshoots in other English-speaking countries, from Canada and the United Kingdom to Australia and New Zealand, the SCM is, in its defense of private property rights against the state and its belief that individual citizens have the right to decide when to ignore the state’s commands, uniquely American in a way that populist nationalism is not—even as its hostility to law and order makes it un-American from the muscular nationalist point of view.

The Peasant Lawyer, by Pieter Brueghel the Younger, c. 1616. Art Gallery of South Australia.

One clue to the character of the SCM is the fact that the main sources of information about it, besides its own videos and websites, are the Southern Poverty Law Center, which tracks hate groups; the Anti-Defamation League, which focuses on anti-Semitism; the Federal Bureau of Investigation, on alert for domestic terrorism threats; and a psychiatrist, George F. Parker, who has made court assessments as to whether individual “sovereign citizens” were sane enough to stand trial for offending against the law (his answer to that question was generally yes). These parties’ interest in the SCM can be traced to what they see as its three most suspect features.

The first is the SCM’s hereditary ties to far-right, anti-Semitic, and white supremacist groups of the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s, largely active in the American West and Midwest, that attributed the machinations of the banks, the U.S. government, and a nefarious New World Order to an international conspiracy of Jews. Prominent among such groups was the Posse Comitatus, which rallied to the cause of farmers crushed by debt, dreamed up many of the “paper terrorism” tactics later used by the SCM, as we shall see, and refused to recognize any legal authority higher than county sheriff. The second is the SCM’s more recent association with aggressively anti-government, Christian, and white-identity groups clustered under the rubric of the Patriot movement, which emerged in the 1990s, gathered steam after the economic crash of 2008, and attracted growing numbers of enraged enemies of “Muslim president” Barack Obama. The third is the SCM’s intense antipathy toward the police as well as its ongoing war against government officials, waged with paper, symbolic, and physical weapons. Sovereign citizens have filed fraudulent tax returns, taken false liens against the property of judges, and flooded the courts with thousands of pages of incomprehensible lawsuits. They have tried government officials in absentia in sovereign citizen courts. They have engaged in gun battles with the police, conspired to assassinate police officers and sheriff deputies, and killed policemen who pull them over for traffic violations. As a result, in 2014, as J. Oliver Conroy reported in the Guardian, the SCM won the dubious honor of being seen by U.S. law enforcement agencies as the country’s most dangerous terrorist threat.

Curse on all laws but those which love has made.

—Alexander Pope, 1717In 2011 the Southern Poverty Law Center estimated that there were approximately 100,000 hard-core supporters of the SCM and perhaps another 200,000 potential or new recruits. Admittedly, it is difficult to quantify membership in a movement that is, according to a 2012 ADL report, “The Lawless Ones,” largely amorphous, led by a variety of self-appointed gurus, reliant on small seminars to spread the word, and allergic to bureaucratic record keeping. Among sovereign citizens are unemployed workers and others in desperate financial straits, ex-certified public accountants, small business owners, ranchers, parents homeschooling their children in order to avoid government-run education, fathers evading child support, drug dealers, money launderers, a few renegade policemen, and scam artists who defraud fellow sovereign citizens by charging them thousands of dollars for phony documents that supposedly will allow them to collect hundreds of thousands of dollars from the U.S. government. In rural regions the SCM has been a white and white‑identified phenomenon, primarily male and primarily middle‑aged, although extremist-movement expert J.J. MacNab has found that it is increasingly attracting younger members of right-wing internet communities who get their news from Infowars and RT. However, in the mid-1990s, sovereign citizen ideas also began percolating through black urban communities, spreading among men in prison in particular and combining with beliefs of an older religious sect, the Moorish Science Temple. The ADL recounts that while whites remain the majority of sovereign citizens in the country as a whole, in many large cities sovereign citizens are more likely to be black.

Although its embellishing details vary, the SCM’s main story line goes something like this: The legal system of the U.S. government was originally based on the Constitution and a common law (but not “common” in the sense of a law based on precedent) guaranteeing every citizen the right to exclude anyone he wished from his person, labor, or property. These citizens, in turn, were equal members of a sovereign people that authorized and delegated powers to the government, not the other way around. At some unclear point—after either the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed citizenship rights to former slaves, the Sixteenth Amendment authorized the government to collect income tax, or the government’s abandonment of the gold standard in 1933—popular sovereignty was subverted and replaced by an “admiralty law” system that surreptitiously pledges its citizens as collateral for its debts by selling their future earnings to foreign investors. This illegitimate government issues every newborn citizen a birth certificate and an application for a Social Security number that transforms flesh-and-blood people into “straw men” with “corporate shell identities,” indicated by the capital letters in which their names are spelled on all government documents. It also sets up, in each of these “satanic” names, a secret Treasury trust fund of anywhere between $600,000 and $20 million. Every “liberty‑loving patriot” who applies for government licenses and permits, pays taxes, receives Medicare payments, or uses a zip code is unwittingly contracting with a government that is out to enslave him. The SCM’s mission is to liberate the flesh-and-blood man from the straw man by unmasking government tyranny and teaching citizens how to repudiate all legal signs of their straw-man identity, withdraw their consent to federal admiralty law, and make it clear to all federal law enforcement officials that their authority extends only over the “federal zone” of Washington, DC; small enclaves of official government property in various states; and the overseas U.S. territories of Puerto Rico, Guam, and the Virgin Islands. To redeem the trust-fund money owed them by the U.S. government, sovereign citizens are encouraged to pay off debts with fake bank drafts and to file fraudulent tax returns with large refund requests. (Aliens residing on American soil are ineligible for the perks of sovereign citizenship, and sovereign citizen philosophy originally held African Americans to be ineligible as well, because they did not enjoy common-law rights before passage of the Fourteenth Amendment.)

The Lawyer’s Last Circuit, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1802. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

A strong Christian element in sovereign citizen philosophy attributes sole sovereignty to God; asserts that individual rights derive from God, not the nation; and, as the Sovereignty Education and Defense Ministry puts it, sees “the word and law of God” as “a sharp sword to expose and cut off corruption wherever it is found, and especially in government.” The SCM otherwise pivots on the principle of the primacy of the sovereign human being. SEDM webinars such as “Citizenship and Sovereignty” and “How to Keep 100 Percent of Your Earnings” instruct the viewer that sovereignty and dependency are mutually exclusive; that you should be your own master in charge of your own life instead of living on government handouts; that unless you consent via a method of your own choosing, you are not obligated to obey “civil statutory laws”; that agreements between you and the government are private contracts, which you can break if the government fails to protect you; that government in fact is a protection racket that assigns you a “public office role” as, for example, licensed dog owner or taxpaying wage worker in order to get its hands on your property; that government is the true terrorist because it uses violence to intimidate its citizens; that domicile is a trick word designed to suck you inside the federal zone, where you will be subject simultaneously to federal and state police powers; that if you are an American citizen and own or work for an American business on American soil, your remuneration is not taxable (no withholding!); and finally, that the state should govern only those who consent to its rule and leave everyone else alone.

The Moorish SCM revises the racial aspects of this story and gives other aspects its own inflection and spin. According to ADL researchers or Moorish spokespersons, the MSCM believes that the Spanish Inquisition is the origin of contemporary politics; that African Moors had a vast inheritance, including North America, stolen from them by Europeans; that African Americans descend from those Moors and have unique sovereign citizen rights and immunities stemming from a 1787 treaty between the U.S. and Morocco; and that secret societies must ferret out these truths, which have been hidden from the black masses through the use of white codes. On the basis of this racial history, it concludes that the current U.S. government is illegitimate, that sovereign citizens are immune from its law, and that paper terrorism can and should be used against its police force and other officials. Because it is highly attuned to black suffering in white society and explicitly allies itself with all African Americans and ultimately with all of humanity, the MSCM is far more collectively minded than its white counterpart.

From Gramsci’s age until our own, rebellions against disruptions of native societies by outside forces most typically have come in the forms of colonized peoples struggling against imperial penetration by the West and indigenous peoples fighting the dispossession of their land by Western settler colonial states. While the MSCM bears a faint resemblance to these anti-colonial movements, today denunciations of an “outside” for threatening an “inside” also exert a magnetic appeal for aggrieved working- and middle-class members of Western national majority groups. These are citizens whose material conditions improved as a result of the same shift from agrarian to industrial economies that preoccupied Gramsci, and who enjoyed a cultural status more elevated than their class status thanks to socially entrenched racial asymmetries but now face new transformations that are turning their rhythms of life, aptitudes for labor, and social position into dust. It is thus ironic but not surprising that right-wing rebellions against globalization are often couched in terms of a right to sovereign power reminiscent of the language used by anti-colonial movements for national self-determination. In turn, the demand for sovereign freedom on the part of historically dominant ethnic majorities in Western countries oddly echoes the demands of beleaguered ethnic minorities seeking national emancipation from persecution by hostile ethnic majorities.

All law is of necessity defective in the beginning.

—Han Yu, 800These new calls for sovereignty reflect the declining potency of once dominant peoples and countries, but they are also part and parcel of an age grappling with a fundamental contradiction.

On the one hand, the principle of sovereign power, which developed in lockstep with the modern state, continues to provide rulers and ruled alike with their political lingua franca. In turn, the ideal of sovereign freedom has riveted the political imagination ever since “the people” wrested the right to rule from their monarchs and became members of a free citizen body—and ever since “peoples” began to identify themselves as blood-and-soil nations with the right to live according to their own lights inside the boundaries of their own sovereign state. The principle of sovereign state power and the ideal of sovereign freedom in either its democratic republican or ethno-national guise have helped set the West’s, and ultimately the world’s, aspirational and institutional political reality for almost four centuries.

On the other hand, contemporary circumstances are eroding the capacity of states to exert exclusive power over their own conditions of existence as well as corroding an international system in which sovereign states are the sole star actors on the world political stage. How can any state be said to be sovereign over its own territory, and how can sovereign states be sole stars, when ideas, cultural influences, and styles of life speed across the globe in a split second before even the most tyrannical sovereign authority can vet them? Or when transnational criminal and terrorist cells, religious warriors, and heads of regional and global institutions compete for the prerogatives of power with presidents and prime ministers? Or when private corporations reshape the globe to expand their profits, which in the case of some corporations are greater than the annual revenue of single states? Or when ecological catastrophes in one place ricochet thousands of miles away and may well inflict irreparable damage on every place and species of being, regardless of anyone’s sovereign will? Or when civil war or economic desperation in one country catapults suffering civilians across national borders with or without the permission of receiving states?

Given the multiplying aspects of globalization that escape the limits of sovereign politics, is it any wonder that anxieties about the loss of sovereign power and freedom abound, even and indeed especially in Western countries that set the rules for the modern state system and were its first and greatest beneficiaries? More exactly, is it any wonder that such anxieties abound among popular segments who have been diminished materially and culturally by globalization, in contrast with those whose wealth and clout have been tremendously enhanced by it—most notably, international economic, technical, and cultural elites? And is it any wonder, finally, that members of a subsegment of that diminished popular cohort become convinced that their nation-states have been hijacked by shadowy global forces and are driven to defend themselves from a behemoth that even some radical leftists have dubbed “Global Empire”?

Aura, by Chris Fraser, 2015. © Chris Fraser, courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco.

In their conviction that individuals can recuperate sovereign power and freedom in an intricately intertwined world by acting as their own lawgivers, sovereign citizens may be even more delusional than populist nationalists, who at least are in tune with the past if not the future course of political history when they assign that project to nation-states. By touting individual sovereignty against both state and global forces, white sovereign citizens also take one giant step further down the road of the politics of atomization than movements touting national sovereignty against transnational institutions and universalistic solidarities. They thereby exhibit an even more severe form of “humanity alienation” than that exhibited by those who refuse to identify with anyone outside a racially cleansed national collective.

At the same time, unlike populist nationalists but like other anti-government groups on the right and left, both white and black sovereign citizens also exhibit a severe case of “state alienation.” Certainly citizens everywhere are susceptible to some degree of state alienation, if only because all human beings are capable of feeling frustration when an institution prevents them from doing what they like—or to poach a thought from Sigmund Freud, when their drives and desires are subjected to civilizationally imposed prohibitions and requirements. Government rules have likely rankled us all at one point or another, but in the U.S. they especially irritate an eclectic assortment of hardline libertarians, country people used to living lives of hardscrabble self-sufficiency, men under the illusion that they have never depended on another human being and so should not be pressed into the service of others, and egotists or narcissists who, as a result of the sheer idiosyncrasies of personality, dismiss the needs and desires of everyone on earth except themselves.

Certainly, too, there is the shock that every self is bound to feel when confronted with the military, disciplinary, and bureaucratic powers that the modern state has at its disposal. The insurmountable inequality between state and individual is best captured by Friedrich Nietzsche’s definition of the state as the restriction of smaller concentrations of power by means of a greater concentration, evoked by his twin metaphors of the state as a beast of prey that sinks its talons into a hitherto formless and nomadic population and as an artist who uses hammer blows on that population to expel a huge quantity of freedom from the visible world. Even with its declining potency in the face of transnational forces, the twenty-first-century state looms ominously large when considered from the angle of the puny individual. Sovereign citizens may be wildly unrealistic about the possibility of clawing back their so-called natural sovereignty from the state, and they may be thoughtless to the point of stupidity about what human life would look like if they succeeded—Thomas Hobbes’ portrait of life in the state of nature as nasty, brutish, and short comes most readily to mind. Nevertheless, in their grasp of the vulnerability of ordinary citizens in the face of an ever-more complex legal system enforced by ever-more heavily militarized police and their sensitivity to the dangers of amassed state power, they are wiser than their populist nationalist counterparts, who not only identify with the state of their dreams but also dream of a state that is hyperauthoritarian.

Do what thou wilt shall be the whole of the law.

—Aleister Crowley, 1904There is, however, a third source of state alienation that has to do not with the repressive capacities or towering stature of the state in general but with the failure of specific states to fulfill their most positive potential functions. The SCM’s fetishism of the independent individual and hatred of the state blind it to the value in any democracy of providing equalizing and community‑building public goods (from education, parks, and worker-safety regulations to affordable housing and clean air and water); ensuring a space for collective action (institutionalized in such a way that everyone living in a place can participate equally in the making of common arrangements about that place); and erecting a public bulwark against private concentrations of power that might otherwise overwhelm single individuals and marginalized groups. State failure to perform these positive democratic functions most frequently occurs as the result of the conquest of the state by dominating races, religions, or sexes; the privatization of public functions by ideological opponents of collective goods; or the state’s corrupt alliance with powerful private interests at the expense of “the simple people.”

Disaffection from a state that turns its back on the many while enhancing the power and wealth of the few is especially relevant in the case of the SCM, given that the appeal of far-right anti-government groups tends to rise during periods of widespread social and economic distress. Many commentators, including Parker and Conroy, note that the popularity of far-right militias among American whites jumped as a result of a farm crisis in the 1980s that led to the mass foreclosure of family farms, while the SCM dramatically expanded during the mortgage crisis of 2008 and the resulting tsunami of home foreclosures. Foreclosures are instigated by banks, insurance companies, investors, and other market actors, but they are backed by state force that protects creditors instead of debtors. Analogously, the appeal of the Moorish SCM grew after decades of mass incarceration of black men whose crimes seemed mainly to be that they were unemployed, semi-employed, illegally employed, or beset by despair-induced addictions, and who were stripped of their right to vote while they languished in prison. In short, a significant degree of state alienation in the United States can be traced to the state’s abandonment of battered populations, both white and black, by supporting procedures through which small‑property‑owning whites (and also, after 2008, many blacks) lost a place of their own on earth—what Hannah Arendt called, in contrast with wealth accumulation, the true meaning of “private property”—and by locking up propertyless blacks consigned to live as human detritus under the hard rule of white power and the cold rule of capital.

That a few hundred thousand people are effectively seceding from the body politic by claiming immunity from its law would be a relatively minor irritant if that body were otherwise intact. But sovereign citizens are in the company of many others who have effectively seceded in less provocative but more corrosive ways. These include elites who have retreated to gated compounds where they need pay only for private services for themselves; companies, families, and celebrities who have hidden their great wealth in tax-free offshore accounts; information technology moguls who have built armored estates for protection in case skyrocketing inequality in America sparks class warfare; and megarich climate‑change deniers whose investments in carbon fuels are helping to exacerbate hurricanes, earthquakes, fires, and floods that already have caused misery for ordinary people from New Orleans to New Jersey to Puerto Rico—at the same time that they have pushed to restructure government so that it is less willing and less able to come to anyone’s rescue. This is to say nothing of the many ordinary Americans who want to withdraw from a global body politic in the making by shutting their doors to people fleeing desperate situations elsewhere, some wishing they could eject nonwhite and non-Christian citizens from the country too. Against this dismal backdrop, the SCM should be seen not as an outlier on the contemporary American scene but as an especially strange and weird symptom of a metastasizing disease that requires not less but more human solidarity to treat and cure it.